Chapter 2

Formation and Development

Although the proclamation of the Commonwealth of Australia for the first of January 1901 brought into effect the Constitution which vested defence power solely with the Federal Government, assumption of that power was at first hollow, as there was neither defence legislation nor military commander to take control and to advise the Minister for Defence. A Secretary with a small staff was appointed to control the Department of Defence on 1 March 1901, but a Commander did not assume control of the Forces until over a year after Federation. The interregnum, until the Commonwealth Defence Act was enacted on 11 March 1904 and proper fiscal authorisation was passed in late 1903, was covered by a proclamation transferring the colonial forces to Commonwealth control, and administering them under their pre-existing colonial defence legislation. Pending the General Officer Commanding's assumption of command, the commandants of the state defence force components continued on under their previously existing defence acts, using carry-on funds supplied by the Commonwealth 1.

Perhaps a fair appreciation of the situation is contained in an article by Boer War Correspondent A.B. Paterson on the state of the new Federal Army, commenting that: 'In their pride at the achievements of our troops in Africa, people are apt to forget that all the commissariat, transport, horse supply, clothes supply and ammunition supply work was done for us by the English officers'. He pointed out the futility of training troops in standing camps so that the transport and commissariat skills were not practiced: 'an army that cannot move is like a snake with its back broken; it is utterly powerless against a mobile foe'. The article further proposed that the Victorian and NSW components should both move for an exercise to Bombala, so that their inability to deploy to an area of operations in fighting condition could be exposed and remedial action taken. These comments were published before it was known who was to be commander of the Forces; Paterson may have rested a little easier if he had known the identity of 'whatever general comes ...’ 2, as it was to be an exponent of mobility in warfare who understood just the problems being propounded.

Lieutenant General Sir E.T.H. Hutton KCB KCMG 1848-1923

His British army service encompassed campaigns in South Africa and Egypt, and he was then appointed Commander of the New South Wales Defence Force 1892-96, during which period he not only revitalised the NSW forces but also promoted cooperation with the other colonies’ forces, and advocated a joint approach to Australian defence.

His British army service encompassed campaigns in South Africa and Egypt, and he was then appointed Commander of the New South Wales Defence Force 1892-96, during which period he not only revitalised the NSW forces but also promoted cooperation with the other colonies’ forces, and advocated a joint approach to Australian defence.

Hutton then moved to command the Canadian militia, which he set about transforming into a national army, followed by service as a mounted infantry commander in the Boer War.

Following Federation he was contracted to command the Australian forces 1902-06. During this period, although hampered by budgetary restraint, he was able to gain control of the drifting ex-colonial forces, and direct their structure and activities to progressing into a balanced national field force.

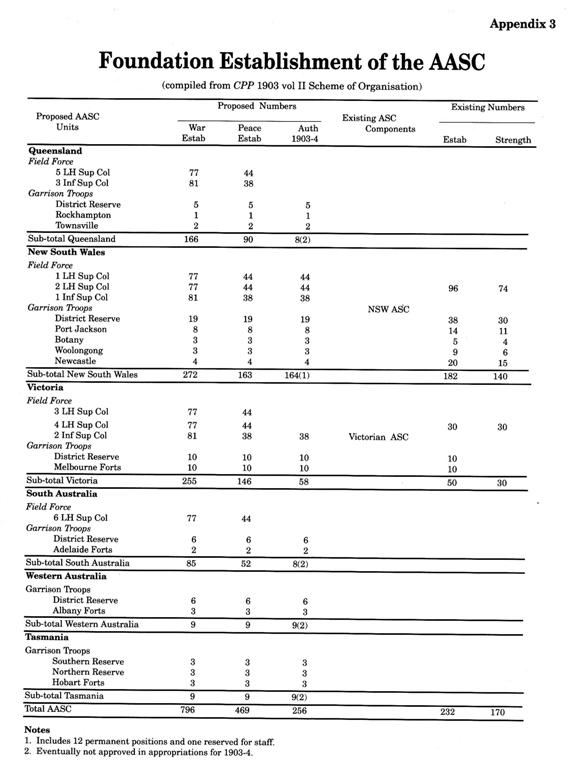

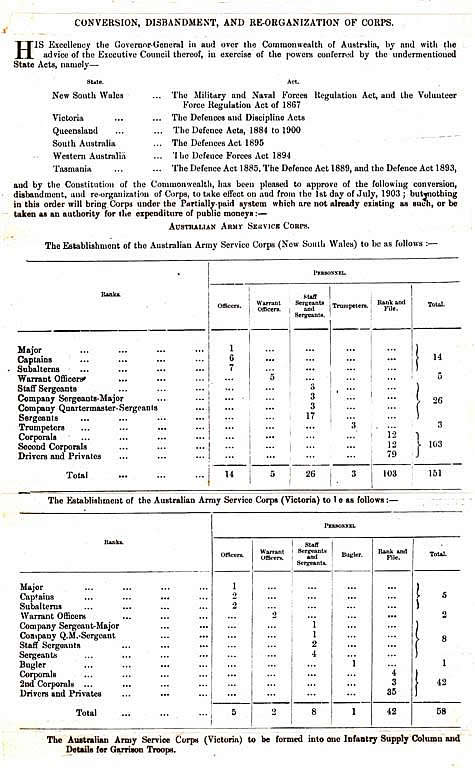

Maj-Gen Sir E.T.H. Hutton assumed command on 29 January 1902; his first step was to begin exercising it, which he did through General Orders and Commonwealth Gazette Notices. Amongst the next steps was to place before Parliament on 7 April 1902 an organisational and financial plan to authorise an appropriate structure of the forces 3. This speedy action brought no response, so he had to submit it again to the budget session the following year, in the interim issuing interim peace and war establishments for field force and garrison troops on his own authority, and operating in a quasi-legal way through the state commandants 4. This command system worked simply because it was the most effective way to control the Army – a system which lasted virtually unchanged for 75 years. But under this regime, whilst proper legal cover was being obtained, the Army Service Corps were left to drift or consolidate, according to local taste. In a 1903 report to Parliament, he summed this up as 'in one state a fairly complete and satisfactory Army Service Corps', in two others, 'a nucleus'. The NSW component was well enough organised, with three companies and establishments allowing for war expansion to provide for the field force; Victoria had slipped back in strength, and about Tasmania he had been misinformed as the ASC authorised immediately before Federation had not been raised; the other states had done nothing at all 5. The status of the elements is shown in the proposed organisation of the AASC which is summarised in Appendix 3.

Sir Edward Nicholas Coventry Braddon KCMG 1829-1904

Premier of Tasmania 1894-1899, he was a proponent of federation and elected as one of the Tasmanian representatives to the Constitutional Convention in 1897.

Premier of Tasmania 1894-1899, he was a proponent of federation and elected as one of the Tasmanian representatives to the Constitutional Convention in 1897.

The draft Constitution gave the Federal Government power to levy customs duties, which were a mainstay of revenue for the colonies: Braddon insisted that the Commonwealth return at least three quarters of duties collected to the states. NSW threatened to withdraw from the Convention, so a compromise was reached where the Barddon Clause (or Braddon Blot) was operative for the first 10 years of federation.

This caused significant restrictions on federal budgets, including Army. Its lifting in 1910 enabled the funding of the Kitchener compulsory service expansion.

Hutton's main priority task was one of rationalisation and dovetailing of the separate colonial forces, each raised against different perceptions of need and expediency, into a force conceived to be appropriate to national criteria. Little in the Defence politico-bureaucracy has ever moved fast, so it is not surprising that his proposals had lain dormant until the budget session of 1903. The context in which they were presented was one of drought-induced fiscal stringency overlying the Braddon Clause in the Constitution which required rebate of excess revenues to the States. The result was reductions and restrictions on Hutton's plans for a coherent and effective defence force. The restricted plans did, however, go through with minor pruning, but these first changes were the herald of many others, both in the short and the long term: Australia's extended periods of 'no discernable threat' 6, allied to periodic economic fluctuations, provided a breeding ground for reorganisations. Change fell most heavily on the support elements of the Army, giving the AASC a roller coaster ride of reorganisation, expansion and contraction.

This first reorganisation was the initial step for a phased expansion based on a permanent cadre, garrison troops to defend major centres from seaborne invasion, and a field force to move against identified threats. As standing armies were, with some justification, widely regarded as instruments of oppression of the people, the Permanent force was restricted to core elements of 'Administrative and Instructional staffs, AASC, Medical and ordnance staffs, Garrison Artillery, Fortress Engineers and Submarine Miners', the AASC cadre numbering 12. The target Militia force was six light horse and three infantry brigades on an aggregate peace establishment of 13,831, with garrison defence and administrative troops making a combined total of 25,844, funded for 1904 to allow raising 22,870; of this 936 were permanent. The funding shortfall for 3,000 meant deferral of raising three light horse and one infantry brigades plus a reduction in existing staffing. The brigade group rather than the divisional system was selected to facilitate deployment of balanced-force groups at short notice, however for the first few years the number and location of brigades actually raised made the possibility of a divisional grouping rather academic 7.

The claims of supply and transport did not lack support from Hutton, whose experience in the Zulu, Soudan and Boer Wars had impressed on him that 'a military force cannot be of any practical value for purposes of war without a carefully-organised and pre-arranged system of Supply and Transport', which led him to recommend that 'an Australian Army Service Corps shall be formed' 8. From this, he clearly did not recognise the existence of an AASC, regarding the current ASCs as no more than the colonial carryover which they were. His plan was for a well defined mobile field force component based loosely on the South African model:

First Line brigade transport Second Line reserve supplies and ammunition Garrison Troops support of garrison defence units

The field force was based on six supply columns (supply and transport companies) for light horse brigades and three for infantry brigades. One column was deferred 'in view of the backward condition of military organisation' in South Australia, two of the three Victorian and both Queensland columns were deferred through financial restrictions, and the second line supply arrangements were set aside for later consideration in conjunction with ammunition columns. Also deferred was a headquarters Supply and Transport staff in consequence of a general reduction in the staff area. The proposals on which the first AASC was established are shown in Appendix 3 9; this model of separate field force and garrison components, as much as titles may have changed, remained the basis of subsequent AASC structure. Its official approval, effective 1 July 1903, consequently also marks the birth date of the Australian Army Service Corps 10.

Hutton has been accused of favouring his erstwhile New South Wales units and officers over those of the other states, and there is no doubt in the reorganisation that the structure and the money went in that direction. While the war establishments were roughly in proportion to State populations, in fact slightly more in favour of the smaller states, NSW took the lion's share in authorised strengths. There would be little doubt that Hutton, like most human beings, leant towards that which he knew and had some confidence in. But there was also another powerful factor – that of the material available: while the NSW forces were maintaining their strength in the first three years of Federation, the other states showed dwindling attendances as the wind down of the war in South Africa and the continuing drought made their effects felt 11. Hutton had earlier laid the base in NSW and returned to find it in good condition, and on the sound principle of reinforcing success, he allotted the resources to keep that part of the Army up to scratch, with the intention of building up the remainder as funds and local capacity to handle expansion allowed. Consequently for the AASC elements all the authorisations went to forming the NSW and lesser Victorian field force supply columns, with garrison details for each State. Pruning of the estimates required further reductions over the proposals in Appendix 3, so the reductions made were single-mindedly to retain the NSW and Victorian components intact and not fund the slender elements for the other four states. Disappointing as this may have been, it was an effective command decision, so different from the compromises which the Army has come to live with in later years.

With Hutton's departure in 1904 the way was cleared for a change to the command system more palatable to the Australian federal approach: establishment of a Military Board, which might give overriding directions on policy matters, but otherwise left all other matters to the Commandants in each State whose responsibilities were extended from 'executive command and training' to include administration and instruction. This notionally returned them to nearly their pre-Federation position, but the reality was something different as becomes apparent later. The Board itself, in line with the rigid limit on staff positions, had three full military members – Chief of the General Staff, Deputy Adjutant General who had AASC tacked on to his personnel responsibilities, and Chief of Ordnance. This was an improvement on Hutton's staff arrangements where transport had belonged to the Assistant Adjutant General and supply to the Assistant Quartermaster General, but it was not until 1909 that a Quartermaster General joined the Military Board and was able to devote adequate attention to logistics matters 12.

Another follow up to the end of Hutton's autocratic rule was an attempt at something of a palace revolution to overturn his brigade structure. A group of senior officers appointed by the Minister to examine defence organisation produced a plan to install a so-called divisional system which was no more than renaming the State headquarters as divisional headquarters, and the garrison defence troops as field force. This name juggling would have produced no real divisions and no more real field force. Within the AASC components, the proposal would have renamed them No 1 NSW Supply Column, No 1 Victorian Supply Column etc, a throwback to the colonial forces which had no place in an army in which Hutton had struggled to 'reorganise six military systems into a Commonwealth military system', and at the same time absorb the various State and Commonwealth contingents returning from the Boer War 13. This report found its way into the parliamentary record, but without ill effect. It is, however, symptomatic of the predilection of so many army officers to draw up trite diagrams of a better scheme of things without real understanding or comprehension of underlying factors or practical application of principles. Fortunately this one failed; unfortunately later ones succeeded.

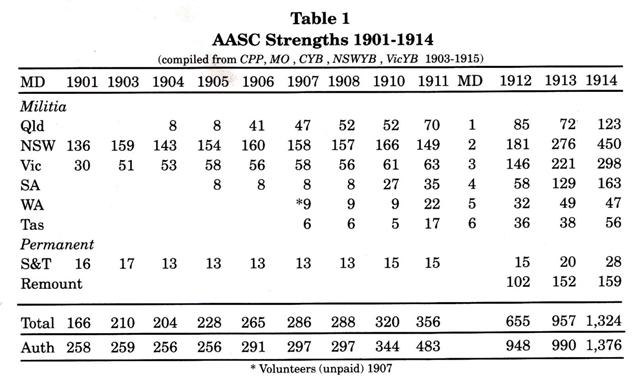

In 1904 funds were found to raise the Garrison Details in Queensland, with clearance for the light horse supply column. In the following year, South Australia and Western Australia's Garrison Details were authorised, the latter as unpaid volunteers; and in 1906 the Hobart element of Tasmania's Garrison Details was approved with Western Australia's Volunteers to be elevated to Militia status the next year 14. The raising of these elements completed the first stage 1903 reorganisation target summarised in Appendix 3. There was no real variation, other than in 1907 following the British lead in cosmetic revamping of Supply Columns as Transport and Supply Columns, until the stirrings of change which followed Kitchener's visit in 1909-10. Average Corps strength was about 300, the Second Line and ammunition column problem had not been addressed, and the Inspector General of the Army continued to applaud the performance of 'arduous and incessant work' and fulminate on the almost total absence of military wagons with the concomitant adverse effects on training. The obvious benefits of having supplies and transport units begin camp before the main body were also reiterated without the funds to give effect to it being found until 1911, when nine extra days per year were authorised 15.

Field Marshal Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener KG KP GCB OM GCSI GCMG GCMG GCIE ADC PC 1850-1916

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, he served as a surveyor in the Near East and in the failed relief of Khartoum. He became governor of the Red Sea Territories and commander of the Egyptian army, recapturing the Sudan after winning the battle of Omdurman in 1898. He was appointed commander of the Imperial forces in South Africa in 1900, bringing the Second Boer War to a successful conclusion, coincidentally signing the death warrants of Lts Morant and Handcock.

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, he served as a surveyor in the Near East and in the failed relief of Khartoum. He became governor of the Red Sea Territories and commander of the Egyptian army, recapturing the Sudan after winning the battle of Omdurman in 1898. He was appointed commander of the Imperial forces in South Africa in 1900, bringing the Second Boer War to a successful conclusion, coincidentally signing the death warrants of Lts Morant and Handcock.

Lieutenant General Sir E.T.H. Hutton KCB KCMG 1848-1923

His British army service encompassed campaigns in South Africa and Egypt, and he was then appointed Commander of the New South Wales Defence Force 1892-96, during which period he not only revitalised the NSW forces but also promoted cooperation with the other colonies’ forces, and advocated a joint approach to Australian defence.

His British army service encompassed campaigns in South Africa and Egypt, and he was then appointed Commander of the New South Wales Defence Force 1892-96, during which period he not only revitalised the NSW forces but also promoted cooperation with the other colonies’ forces, and advocated a joint approach to Australian defence.

Hutton then moved to command the Canadian militia, which he set about transforming into a national army, followed by service as a mounted infantry commander in the Boer War.

Following Federation he was contracted to command the Australian forces 1902-06. During this period, although hampered by budgetary restraint, he was able to gain control of the drifting ex-colonial forces, and direct their structure and activities to progressing into a balanced national field force.

After a term as Commander in Chief in India and a failed attempt to become Viceroy, he toured the Empire, in the process preparing a report for the Australian government recommending a restructuring from the Hutton army to cope with the expansion arising from his recommended military conscription of all Australian youths.

In World War 1 he was Secretary of State for War, establishing the manpower and munitions necessary for the great prolonged and intense effort which he predicted. He died when a warship carrying him to a conference in Russia was sunk by a German mine.

The stirrings arising from the report on Australian defence prepared by Lord Kitchener, combined with the outcome of the Imperial Defence Conference of 1909 and an easier Commonwealth financial situation with the suspension of the Braddon Clause in 1910, had earlier ramifications than just the reorganisation of 1912. An arms race in Europe and Australian scepticism of the value of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance supported moves to a stronger defence commitment 16. While Kitchener recommended a system of universal training to support an expanded capability, the mechanics of this were not immediately implemented, nor would the full effect be felt for eight years. In the interim, an expansion to meet the unachieved targets of the second phase of the 1903 reorganisation was commenced. Authorisation of the transport and supply columns for South Australia's light horse brigade in 1910 and Victoria and Queensland's infantry brigades in 1911 completed the nine columns of the Hutton plan. In addition the amalgamation of garrison defence units with the field force in Western Australia and Tasmania produced the scope to raise restricted columns for the resulting 'mixed brigades' in the same year 17.

By 1911 these units had been raised and the AASC had taken on the management of Army horses through remount sections in each capital, but the question of lines of communication units was still to be addressed. The 1909 Imperial Defence Conference had agreed on standardisation of forces on the British model, with a suggested scale of six depot units of supply per division and two per mounted brigade, plus a bakery section per division or three mounted brigades. But as the Australian effort was directed to fleshing out the existing brigade columns, no move on this was made, and the whole issue was then overtaken by the upcoming 1912 Universal Training reorganisation. Instead, the Inspector General directed attention to the existing columns developing a capability for field butchery and bakery 18. And at the end of this phase of the development of the AASC, in line with Kitchener's proposal that a proper Army staff be established to prevent trivia being brought before the Military Board, a Director of Supply and Transport was appointed to the Quartermaster General Branch of Army Head-Quarters. While the provision of a captain was by no means a lavish allocation, it at last recognised this growing function which would be tested by the demands of Universal Training.

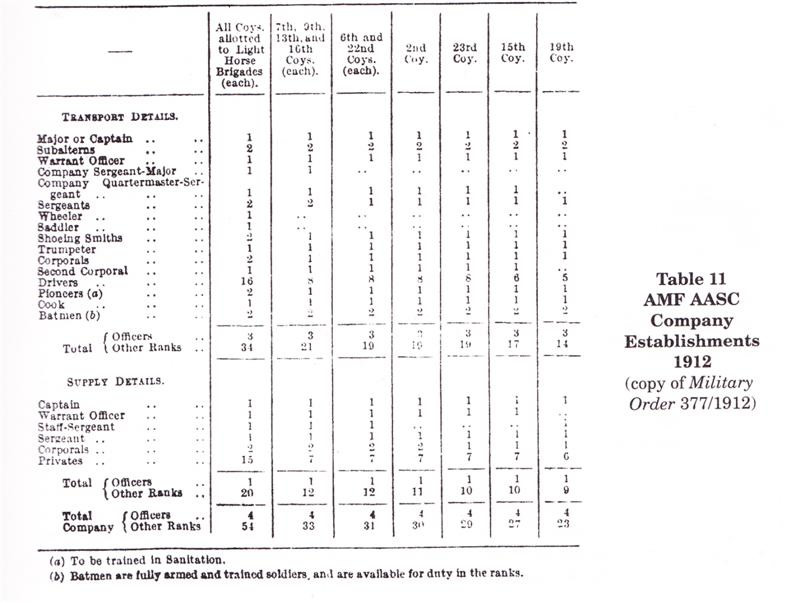

Kitchener's report of 1910 proposed a Militia force of 80,000, to be raised and maintained by a universal training scheme conscripting youths in the 12 to 18 age bracket as cadets, who then passed into the Militia until aged 26. The Universal Training scheme was accepted and legislated to begin in mid-1911, which meant that the first output from Senior Cadets inducted at age 17 would transfer into the Militia units in 1912, building up the force steadily until the target and equilibrium were reached in 1919; events were to overtake this scheme well before that stage as is so often the case with deferred threat scenarios. The organisational side of the report proposed that the country be divided, according to the electoral rolls, into 215 approximately equal training areas, each with an officer in command, and these grouped by tens into larger formation areas incorporating a balanced mix of units approximating a brigade, with a superior instructor who was to become the brigade major of that formation in war. Each of these 21 formation areas was to have an AASC company, though this plan was increased progressively during implementation to eventually 35 companies 19.

Table 1: AASC Strengths 1901-1914

Lieutanant Colonel Jxxxx Txxxx Marsh CMG 18xx-19xx

Seconded from the British AASC to at last provide for a director for the AASC and Chief Instructor of AASC Training in 1910, he failed to provide the direction required, being more content to criticise than improve. State Commandants and British inspecting officers Kitchener and Hamilton didn't agree with his carping about standards of his Corps members.

On the outbreak of World War 1 he managed to organise himself command of 1 Div Train AASC headed for Egypt and France, leaving the burden of supporting the wartime expansion to Warrant Officer Heydt.

With such an expansion and the certainty of continual turnover of men, training became a principal activity. In addition to the Area Officers allotted to supervise all arms training, special staffs were allotted to each corps in each district to assist in training of their Militia units; the AASC component was to be five officers and 12 NCOs. This proceeded slowly under the competitive pressure of a rapidly expanding force, so by early 1914 only two officers and 11 NCOs were in place, though this was fortuitously improved over the following months, barely in time for the extraordinary demands following the outbreak of war. The officers were given the additional function of Assistant Director of Supply and Transport on their district headquarters 20, so providing a technical network from the Director at Army Head-Quarters, and also establishing a local controller of supplies and transport arrangements in the much multiplied contractual system for civilian suppliers demanded by the expansion. The services of two officers of the British Army Service Corps had been acquired to give a depth of experience to the increasing Corps – one became first Director of Supply and Transport and the Chief Instructor of ASC Training, the other Assistant Director of Supply and Transport of 2nd Military District and the national Inspector AASC on the Inspector General's staff, however their unimaginative performance later as commanders of 1st and 2nd Division Trains on Gallipoli calls in doubt their ability to invigorate this earlier area either. Indeed DS&T Capt Marsh's pedestrian approach is exemplified by his complaint in mid-1913 about the 'extreme youth and inexperience of the majority of ASC officers', comparing this with the 'TA at home' which selected experienced businessmen. The Military District Commandants, well aware of the growing confidence and vigorous performance of their AASC units, dismissed this as ill informed and ill considered 21.

Paralleling this expansion was the reorganisation of the British system of supply and transport in the field which, by virtue of Australian endorsement of the 1909 Imperial Defence Conference principle of standardisation, became the target if not the practical basis of the new structure. The system involved concentration of all transport, other than that which formed the basis of combat unit fighting capacity, into a horse transport divisional train carrying unit baggage and a day's food and forage. These trains were to be replenished daily from railhead by motorised supply columns, with field bakeries and butcheries operating near the railway, and a horse transport reserve park to hold and move an emergency reserve of rations. Divisional ammunition columns were horsed artillery units with the major task of delivering gun ammunition but with an ASC component for infantry etc ammunition; ASC ammunition parks with integral mechanical transport delivered from railhead to divisional ammunition column 22. But adoption of this within the Australian Army was inhibited by two barriers - the dispersion of the Army throughout its natural recruiting areas, which hindered divisional support groupings, and the slim chances of getting any significant mechanical transport resources when budgets had baulked at providing more than a token number of horse-drawn wagons. The structural reality was a collection of light horse and infantry brigade composite transport and supply companies, established as shown in Table 11, dedicated to training and the administrative support of training in their areas. From the 11 understrength transport and supply columns, two garrison companies and five garrison details on the order of battle of the Hutton Army, the AASC opened the Kitchener phase with 16 companies which increased in number as the annual Universal Training inputs demanded more units to hold them. By 1914 the structure was 23:

| 1st Military District | 1, 2, 3, 24 Coys |

| 2nd Military District | 4,5,6,7,8,9,26,27 Coys |

| 3rd Military District | 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 28, 30 Coys |

| 4th Military District | 19, 20, 31 Coys |

| 5th Military District | 22 Coy |

| 6th Military District | 23 Coy |

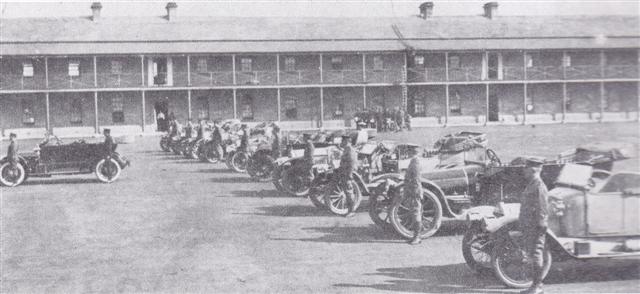

Expansion demands and the effects of dilution of experience had made their impact on the standards of the Corps. While prior to 1911 it is difficult to find adverse comments, rather universal praise was the norm. the Inspector General became increasingly critical of standards, blaming a lack of opportunity to exercise the AASC units in their tasks during formation training and too great a reliance on contractors. He further criticised supply officers for their lack of technical competence and, more seriously, sheer lack of responsibility in not being in control of the supplies situation. He hoped that universal training would provide a source of tradesmen to improve technical competence, and recommended a badly needed increase in the number of Permanent staff for instructional purposes; a positive note was struck in the use of hired motor lorries in NSW and Victoria 24. There was, of course, no planning to introduce these as service equipments when the Army could afford few horse wagons of its own, but at least progressive minds were taking forward-thinking initiatives to solve problems rather than sitting passively with those content to bemoan the demise of the stock horse and debate the merits of German wagons. But there were indeed two motorised corps in the Army, one the Flying Corps in 1913, where the logic of having motorised aircraft flowed easily to motorised land vehicles, although perversely the real logistics carriers could not carry an even stronger argument. The other was something of an AASC competitor in the form of the Australian Volunteer Automobile Corps formed in 1908, a bring-your-own-car means of providing a field reconnaissance capability, and coincidentally staff transport, without the capital costs of military procurement, much the same as that of horsemen providing their own horses on repayment. The former grew and its successor bid to take over motor transport in 1922, the latter languished and was absorbed into the AASC in 1916 25.

Generall Sir Ian Standish Monteith Hamilton GCB GCMB DSO TD 1853-1947

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, he served in the Gordon Highlanders in the Afghan War 1879, then in the First Boer War 1881 the Nile expetition 1882-85, several campaigns in India, and the Second Boer War as Kitchener's chief of staff. He was twice recommended for the Victoria Cross, both not accepted – the first time as too young, the second as too senior.

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, he served in the Gordon Highlanders in the Afghan War 1879, then in the First Boer War 1881 the Nile expetition 1882-85, several campaigns in India, and the Second Boer War as Kitchener's chief of staff. He was twice recommended for the Victoria Cross, both not accepted – the first time as too young, the second as too senior.

Hamilton was present during the Russo-Japanese War 1902-05 as military attache to Japan of the Indian Army, noting the emergence of industrialised warfare, and the combination of entrenchments, artillery, machine guns and fire and movement. This prompted him to declare the uselessness of cavalry in such warfare, and support for night attacks and aircraft.

Field Marshal Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener KG KP GCB OM GCSI GCMG GCMG GCIE ADC PC 1850-1916

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, he served as a surveyor in the Near East and in the failed relief of Khartoum. He became governor of the Red Sea Territories and commander of the Egyptian army, recapturing the Sudan after winning the battle of Omdurman in 1898. He was appointed commander of the Imperial forces in South Africa in 1900, bringing the Second Boer War to a successful conclusion, coincidentally signing the death warrants of Lts Morant and Handcock.

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, he served as a surveyor in the Near East and in the failed relief of Khartoum. He became governor of the Red Sea Territories and commander of the Egyptian army, recapturing the Sudan after winning the battle of Omdurman in 1898. He was appointed commander of the Imperial forces in South Africa in 1900, bringing the Second Boer War to a successful conclusion, coincidentally signing the death warrants of Lts Morant and Handcock.

After a term as Commander in Chief in India and a failed attempt to become Viceroy, he toured the Empire, in the process preparing a report for the Australian government recommending a restructuring from the Hutton army to cope with the expansion arising from his recommended military conscription of all Australian youths.

In World War 1 he was Secretary of State for War, establishing the manpower and munitions necessary for the great prolonged and intense effort which he predicted. He died when a warship carrying him to a conference in Russia was sunk by a German mine.

Although his command the Gallipoli campaign was generally criticised on the outcome, Australian war historian C.E.W. Bean assessed him as 'a breadth of mind which the army in general does not possess'.

Appointed GOC Mediterranean and Inspector-General of the Overseas Forces in 1910 he inspected the Australian Commonwealth Military Forces immediately before the outbreak of World War 2 and reported very favourably on the state of the Australian Army Service Corps as 'this is a highly satisfactory and efficient branch of the Commonwealth Service’

After the Gallipoli withdrawal he was given a sinecure, but in the postwar years became active in the British Legion.

The following two years were put to better effect, with the Inspector General expressing improving satisfaction with the ration and forage situation; and finally in 1914 a report by visiting General Sir Ian Hamilton that he found of the AASC 'this is a highly satisfactory and efficient branch of the Commonwealth Service’ 26. The most satisfactory aspect of this statement is that it was not a mere platitude of a visitor, but part of a hard hitting report which did not hesitate to hand out brickbats where he felt was warranted, as was Hamilton's wont. The AASC was as well prepared for World War 1 as the limitations of resources and training had allowed: it remained to be seen how these units would be tested in the coming war.

Footnotes

1. CPP 1906 vol II Report on the Department of Defence, p4-5; Perry W. 'Australia's Immediate Post Federation Military Forces' Australian Army Journal June 1976, p32-3; CPP 1902 vol II Hutton Report, p5.

2. Sydney Morning Herald 13 July 1901 'Our Federal Amy and its Cost', p4.

3. CPP 1901-2 vol II Minute Upon the Defence of Australia by Major General Hutton Commandant, p56.

4. Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No 35 of 29 July 1903, p396-407; General Order No 1 of 1 March 1902.

5. CPP 1903 vol II Hutton Report, p18-9.

6. CPP 19031-2 vol II Hutton Minute, p1; Report by Capt Creswell on the Best Method of Employing Australian Seamen in the Defence of Commerce and Ports, p3 and Appendixes B, C; CPP 1905 Report by the Naval Director. to the Honourable Minister of State for Defence, p2.

7. CPP 1903 vol II Hutton Report, p12, 17-8; Scheme of Organisation, p23-4.

8. CPP 1903 vol II Hutton Report, p18.

9. CPP 1903 vol II Scheme of Organisation, p2-24; for war establishments see Table 11.

10. CAG No 35 of 25 July 1903, p396, 399, 401; unit titles authorised in CAG No 61 of 31 October 1903, p760.

11. CPP 1903 vol II Hutton Report, p35.

12. CPP 1904 vol II Defence Forces – Memorandum by the Minister for Defence, p2; 1909 vol II Memorandum on Australian Military Defence and its Progress since Federation, p6.

13. CPP 1906 vol II General Scheme for the Defence of Australia. Report by a Committee of Officers, p5; 1903 vol II Hutton Report, P73.

Major-General Henry Finn CB mid 1852-1924

An imperial officer of the 21st Hussars and 21st Lancers, Harry Finn served in the Afghan and Nile Wars, and at the battle of Omdurman.

An imperial officer of the 21st Hussars and 21st Lancers, Harry Finn served in the Afghan and Nile Wars, and at the battle of Omdurman.

He was seconded as Commandant in the rank of colonel of the Queensland Defence Force 1900-01, and after the federation transfer of the colonial forces to the Commonwealth Military Forces, as a brigadier-general Commandant of the of the New South Wales component 1902-04.

In 1904 he was appointed as Inspector General of the CMF, reporting independently to federal parliament annually on the condition of the forces and recommending changes and actions, holding this position until 1906.

He was described in the Senate as 'the ablest military man in the Commonwealth' and as a man possessing 'grit, determination, ability and backbone' but had an adversarial relationship with Minister for Defence Playford, and considered the Military Board's unresponsiveness to his recommendations unworkable, returning to England after expiry of his appointment.

14. CPP 1907-8 vol II Report by the Military Board 1906, p12; 1906 vol II Annual Report by the Inspector General of the Commonwealth Military Forces Maj Gen H. Finn 1905, p17; 1906, p12.

15. CPP 1906 vol II Finn Report, 1905, p17; 1906, p12.

16. Tanner T.W. Compulsory Citizen Soldiers p138-9, 184-5.

17. Military Order 2/1911; CPP 191l vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p3.

Lieutenant-General Sir George Macaulay Kirkpatrick KCB KCSI 1866-1950

Field Marshal Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener KG KP GCB OM GCSI GCMG GCMG GCIE ADC PC 1850-1916

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, he served as a surveyor in the Near East and in the failed relief of Khartoum. He became governor of the Red Sea Territories and commander of the Egyptian army, recapturing the Sudan after winning the battle of Omdurman in 1898. He was appointed commander of the Imperial forces in South Africa in 1900, bringing the Second Boer War to a successful conclusion, coincidentally signing the death warrants of Lts Morant and Handcock.

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, he served as a surveyor in the Near East and in the failed relief of Khartoum. He became governor of the Red Sea Territories and commander of the Egyptian army, recapturing the Sudan after winning the battle of Omdurman in 1898. He was appointed commander of the Imperial forces in South Africa in 1900, bringing the Second Boer War to a successful conclusion, coincidentally signing the death warrants of Lts Morant and Handcock.

After a term as Commander in Chief in India and a failed attempt to become Viceroy, he toured the Empire, in the process preparing a report for the Australian government recommending a restructuring from the Hutton army to cope with the expansion arising from his recommended military conscription of all Australian youths.

In World War 1 he was Secretary of State for War, establishing the manpower and munitions necessary for the great prolonged and intense effort which he predicted. He died when a warship carrying hom to a conference in Russia was sunk by a German mine.

A Canadian-born British Army Royal Engineer, he served on Kitchener's headquarters staff in the Boer War, then the Indian Army.

In 1910 he was seconded on exchange to the Commonwealth Military Forces, appointed temporary major general, as Inspector General of the Commonwealth Military Forces, reporting annually to parliament on the state of the forces and recommending remedial action.

Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges KCB CMG 1861-1915

Migrating to Australia in 1879, he was commissioned in the NSW Permanent Artillery and sent for training in UK. After return, he became Chief Instructor at the School of Gunnery, then went to the Boer War with the British Army then was evacuated medically. Rapid promotion saw him as AQMG at AHQ, Chief of Military Intelligence and Chief of the General Staff, then sent to England as Australia's member on the Imperial General Staff.

Migrating to Australia in 1879, he was commissioned in the NSW Permanent Artillery and sent for training in UK. After return, he became Chief Instructor at the School of Gunnery, then went to the Boer War with the British Army then was evacuated medically. Rapid promotion saw him as AQMG at AHQ, Chief of Military Intelligence and Chief of the General Staff, then sent to England as Australia's member on the Imperial General Staff.

Then followed promotion to brigadier-general as inaugural commandant of the Royal Military College Duntroon. In 1914 he was appointed as Inspector General of the Army, following Kirkpatrick but the outbreak of Worl War 1 saw him appoined to command 1st Division, Australia's initial contribution. The division was committed to Gallipoli where Bridges was mortally wounded by a sniper; he was knighted immediately befor his death.

He served in this position until 1914 when replaced by Maj Gen W.T. Bridges, electing to retire in Australia, and becoming the honorary colonel first of 60th (Princes Hill) Infantry Battalion, then in 1921 its successor 6 Inf Bn.

18. CPP 1909 vol II Conference on the Naval and Military Defence of the Empire, p44, 48; CPP 1912 vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p16, 17.

19. CPP 1910 vol II Memorandum by Field Marshall Viscount Kitchener of Khartoum, p5-7, 11; 1912 vol II Report on the Progress of Universal Training to 30 June 1912, p5; Army List of the Australian Military Forces 1913-21 (this list is known by a variety of names over the Commonwealth period including Regimental List and Officers List; it will in future be referred to as Army List).

20. CPP 1914 vol II Report on an Inspection of the Military Forces of the Commonwealth of Australia by Sir Ian Hamilton, p13.

21. MO 269/1912; Army List 1913; see Chapter 14 of this volume on Gallipoli; Australian Archives MP2023 21/6/6 Memorandums of 5 May, 14 August et seq.

22. Beadon R.H. The Royal Army Service Corps vol II p53-5.

23. MO 428/1912; 1/1914 and amendments.

24. CPP 1911 vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p10-11; 1912 vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p16.

25. MO 570/1912, 148/1908; see Note 15 to Chapter 3.