Chapter 14

World War 1

The Home Front

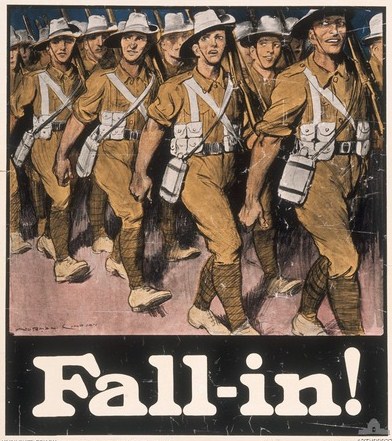

When news of the declaration of war against Germany reached Australia, the government and people plunged in to support Britain and the Entente with the same fervour as had marked the earlier colonial adventures. There were of course doubters who grew in numbers as the nature, extent and cost of the war became clearer and war weariness set in. However the war psychosis which had built up in the pre- and post- declaration period ensured that Australia would be firmly committed to this 'war to end wars'. The Australian approach to the conflict resolved itself into three major objectives: the first was protection of the homeland from attack; the second, pre-emption of such attack by elimination of German military and naval forces in New Guinea, the Pacific and the Indian Oceans; and the third the honouring of undertakings to participate in imperial defence agreed in principle at successive Imperial Conferences and a matter of bipartisan political policy in Australia 1.

In pursuance of the first objective, on 2 August 1914, two days before war was declared, militia units were called out for coastal defence duties and protection of vulnerable areas of ammunition, communication and transport facilities. These guard duties were progressively taken over by a special corps of volunteers who were unfit for service overseas, a garrison military police corps, and for naval installations, a naval guard section 2. The second and third objectives were prosecuted by the offer of forces to the British Government and responding to British urging to deal with the German territories. The first move was an offer on 3 September to 'despatch an expeditionary force of 20,000 men of any suggested composition to any destination desired by the Home Government'; the offer also included placing the main naval units under Imperial control 3. This met the third objective and part of the second, as the fleet units were used in the effort to counter the German fleet in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The final part of the second objective was addressed in response to a British cable of 6 September suggesting that the elimination of the German territories 'was a great and urgent Imperial service' 4: accordingly a secondary expeditionary force was authorised.

As the Defence Act precluded use of the AMF's conscriptees overseas, two volunteer expeditionary forces had to be raised, trained and dispatched to their theatres of war: the smaller, the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force to go to New Guinea and the Islands, the second and much larger one to the European theatre. This left that greater part of the AMF which was not absorbed into those forces to continue on as a compulsory, universal training-based militia in its normal training areas once the guard commitment eased 5.

Recruiting for the Army presented little enough difficulty – at least at first. The AMF was ensured of a steady infusion from its universal trainee cadet source which, as more cohorts entered the call up, in fact increased the number of AASC companies from its prewar 24 to 29 shortly after the war and 35 in 1920 6. Response to the initial call to arms for volunteers for the ANMEF and AIF was so strong that there was no difficulty in seeing the former embarked for New Guinea by the end of August, the First Expeditionary Force for Europe achieving its quota by the same time, and the extra units and reinforcements meeting their target in September. Area recruiting officers and local government officials authorised to enrol volunteers faced the pressures of induction – organising medical and transport arrangements for the flood of candidates – rather than those of inducement of men to come forward. The call for reinforcements in November met an ominous lukewarm response, and except for spontaneous surges after major losses in Gallipoli and the Western Front, recruiting for the AIF became a hard sell campaign passed first in October 1915 to State War Councils and their recruiting committees, then to a Defence Department recruiting officer system a year later. Failure of successive referendums to authorise conscription for overseas service in November 1916 and December 1917 threw the reinforcement problem back on a system of exploring the many faces of persuasion which on occasion bordered on coercion 7.

Difficult as it was to maintain the field units at strength, it was fortunate that the savings in the overseas infrastructure through support provided by the British Army in general and the British Army Service Corps in particular prevented a significant diversion of manpower to base support functions. After the earlier expansions to form the six divisions of 1916, AASC numbers in the AIF remained relatively stable even though it took over responsibility for motorised support completely from the loaned ASC units on the Western Front, the progressive streamlining of Australian Army Service Corps units tending to offset increases in numbers of units. But all this was not without its penalties for the home army. By late 1917 the steady leakage of militia officers and NCOs and permanent instructors to the AIF had bled the AMF units to the stage where they were 'skeleton units composed of youths inadequately officered and necessarily inadequately trained'. The remedy was a series of amalgamations of major units in order to pool the available officers, NCOs and instructors though not for AASC units which were simply later renumbered to match the new training areas 8. But with an end to the drain of the AIF a year later, the militia climbed back towards its Kitchener target, buoyed by the stream of AIF returnees available as war-experienced instructors. The threat from Germany and Turkey had been in fact remote, and Japan for the moment was a firm ally, so the home defence Army filled its multifaceted roles of keeping alive a recruiting and training ground for the AIF, a gadfly for those who declined to volunteer and a visible martial presence on the home front.

Despatch of the AIF was an immediate load on the Director of Supply and Transport. The incumbent applied for and was immediately accepted as commander of 1 Div Train, leaving his assigned post forthwith with his staff in tow, just as the going became tough. The Directorate was responsible, apart from basic AASC responsibilities, for rail, road and sea transport, accommodation, canteens, food, forage, fuel and cooking. Assembly, training, equipping and shipping of the first and follow up contingents for Europe in October and December needed all these services in unprecedented quantities. A makeshift Directorate headed by Lt H.E. Heydt got to work, arranging rail and shipping schedules, temporary accommodation and feeding for the 20,000 men and nearly 8,000 horses from all States involved. The sheer magnitude of the task was overcome only by the direct intervention of Quartermaster General Brig-Gen J. Stanley, the dedication and urgency of Heydt and his assistants, and the soundness of both the ADS&T staffs in the military districts and of Lt-Col P.T. Owen who became Military Transport Officer, supervising the preparation, loading, dispatch and later reception of transport ships. In the course of the war this organisation provided the training camps, food, fuel, canteens and transport for 331,781 men on their way overseas, as well as ongoing support for the 100,000 man Militia 9.

South West Pacific

Australia had needed little enough prompting to deal with the German Pacific territories. European penetration into the Pacific had been a source of concern for over 70 years, and in particular the German move into New Guinea had pushed Queensland, on behalf of the Australian Colonies, to annex Papua for an unwilling Home Government in 1884. The AN&MEF was raised was different from the AIF in that it was equipped and supported completely from Australia. The mounting base of the Army component was 2nd Military District, whose Assistant Director of Supply and Transport arranged the majority of the external support required for the campaign, which was just as well as the remnant at DST, struggling with the shipping of men, horses and materiel for the AIF, had no capacity to address this other problem. The fact that the operations were basically seaborne meant that the fleet units and support vessels could be used as support bases, so removing any requirement for Army logistics units. The later military administration in the captured territories relied on civil resources for its local supply and transport arrangements, so no AASC units were deployed to the captured territories 10.

Defence of Egypt

The first AIF and New Zealand contingents reached Egypt at the end of November 1914. The AASC overseas component was progressively built up by February 1915 to include 1st Division's integral Divisional Train (1, 2, 3, 4 Coys), supporting corps troops Supply Column and Ammunition Park (8, 9 Coys) and Reserve Park (10 Coy), and line of communication units 1st and 2nd Depot Units of Supply and 11th Railway Supply Detachment (11 Coy), 1st Field Bakery and 1st Field Butchery (13 Coy); and for non-divisional formations 1st, 2nd, 3rd Light Horse and 4th Infantry Brigade Trains (5, 6, 12, 7 Coys). Arrival of additional combat units brought with them by July that year 4th Light Horse and 5th, 6th and 7th Infantry Brigade Trains (14, 15, 16, 17 Coys) and later in the year 8th Infantry Brigade Train (18 Coy). The destination of the first contingent had been England to prepare for deployment in France, but the British Government was unable to provide acceptable accommodation in time, and the example of the Canadian contingent already inhibited in its training and suffering from the winter conditions on Salisbury Plain cautioned against a similar destination. In consequence the convoy was diverted to Egypt, except for the motorised Supply Column and Ammunition Park which continued on to England, less their supply and ammunition sections 11. In the Egypt base, training and equipment were to be completed prior to on-movement to France, but this move was once more pre-empted by the Gallipoli plan.

Immediately after arrival in Egypt 1 Div Train companies were thrown into the unexpected task of support of the Australian camps established at Mena and Maadi near the Great Pyramids. This involved not just forward distribution but also the establishment of a base supply depot with refrigerated storage, using peace accounting procedures and letting and operation of contracts for foodstuffs and forage after an initial issue from the British Main Supply Depot. 1 Fd Bky organised bread production in ovens reputed to have been set up for Napoleon's Army of the Nile in 1798. The AASC transport was late in arriving, so mule and donkey carts provided an inferior interim substitute, augmented by some motor cars donated to the AIF before departure by patriotic citizens, some of whom also enlisted to drive them. Arrival of the wagons and horses ended one problem but opened others – restoring horses wasted by the long sea voyage, then coping with the sand and modifying the General Service wagons, so hurriedly constructed in Australia at the outbreak of war, to meet the stresses of teams of up to 16 horses pulling them through difficult patches of sand. This strain also meant constant work for the unit artificers in repairing equipment and harness. When all had settled into a routine, the most notable problem was unavailability of the normal type and quality forage: chopped straw with crushed maize and barley was the best local substitute for chaff and oats 12.

Redeployment to the Gallipoli force assault base of Lemnos began at the end of February 1915 for one brigade group including 4 Coy, followed over a month later by the remainder of the A and NZ Army Corps. 13 Coy's 1 Fd Bky baked on the Malda in Lemnos Harbour, its 1 Fd Bchy slaughtered on the shore and 1 DUS issued rations from on board to the troops on the various ships of the invasion fleet riding at anchor. Remaining in the Egyptian base of the AIF were the light horse brigades with their trains, the base staff, reinforcements, hospitals, left-out-of-battle parties including 10 Coy AASC (Reserve Park), and surplus kit and stores. To this group in May was added the transport sections of the divisional trains when the stalemate on Anzac rendered their landing there pointless 13. During the course of the Gallipoli campaign these units were added to by the ongoing arrival of reinforcements from Australia, casualties from the Peninsula and the trains of the additional light horse and infantry brigades. They were depleted by the dispatch to Gallipoli of trained reinforcements, dismounted light horse reliefs, and in September, of the 2nd Division with the supply elements of its divisional train which had been formed up in Egypt from 4 LH, 4, 5 and 6 Inf Bde Trains (4, 15, 16, 17 Coys) 14.

The AASC rear parties were employed as part of the infrastructure of the base, but this routine was interrupted when a threat developed from the Senussi tribes in the Western Desert. Western Frontier Force was organised to respond, comprising two brigades of British, Indian and New Zealand troops, with an Australian light horse composite regiment, supported by the transport element of 1 Div Train. From 29 November to 2 December 1, 2, 3 and 4 Coys were deployed by rail to Dabaa. From there on 4 December half of 4 Coy escorted by 15 Sikh Bn established a series of supply points forward on the route to Mersa Matruh. The force followed with the rest of the Train, including the other half of 4 Coy arriving, after a difficult drive over waterless desert, by 11 December. On the same day a battalion group pushed west against light opposition to Umm Rakhum, where it was joined by 4 Coy under Lt C.E. Thomas on the 12th. The next day the force continued west, leaving 4 Coy at the camp, but on running into strong opposition and being threatened with encirclement, the commander signalled the camp by heliograph for assistance. 4 Coy responded 'full of fight' with 75 riflemen in three platoons under Thomas, Lt L.F. McQuie and the transport officer of 6 Royal Scots, with a machine gun of the latter battalion sent across in support. Their task was to clear the Arab elements which had infiltrated the wadis behind 15 Sikh Bn. The machine gun ammunition limber became stuck and Thomas led two mules under fire to bring it in, being fatally wounded in the process. Sgt A.J. Sanders took command of Thomas' platoon and, finding the Royal Scots officer inactive, took the initiative in successfully launching the clearing operation. Additional casualties were one killed and five wounded.

Further indecisive actions continued for the remainder of the month, the Divisional Train receiving resupply through the port at Mersa Matruh. Heavy rain immobilised the force for the first part of January until the 12th, when a column, including all 1 Div Train, launched an abortive attack on a camp at Gebel Howeimil. On the 24th, the Train supported another thrust on the main Senussi camp at Halazin. By midday the wagons had become bogged, and had to form a defensive laager overnight, pressing on the following day to feed the column and evacuate the wounded. A final drive on Sollum with an expanded force was launched on 18 February. 1 Div Train supported this action as far as Umjeila, was then relieved and returned to Cairo to join in the reorganisation of the AIF described in Chapter 3. Although this campaign was minor compared with the others involving the AIF, it was handled with distinction by the Train, and provided some small compensation for being left out of battle from their comrades at Gallipoli 15.

While the threat from the west was being mopped up, another had reared its head again in the east. A Turkish attack across the Suez Canal in early February 1915 had been easily repelled by mostly Indian troops, with only minor commitment by Anzac units. Now a year later further Turkish deployments to southern Palestine signalled a build up for another attempt. 1st and 2nd Divisions were moved to positions in front of the Canal on 23-4 January 1916. Two forward bases were established on the east bank of the Canal – one for each division, with a road, light railway and water pipeline leading to each of the divisional areas; 1 and 2 DUS issued forward from the each of the railheads by branch roads, Deceauville tramways and water pipelines to the forward areas. 1 Railway Supply Detachment, having been frustrated in its attempt to establish a railway on Gallipoli, now came into its own, augmented by train drivers found amongst other units. However, for all the effort put into establishing these defensive works, and also the support infrastructure behind it, they were quickly abandoned – defence of the canal was to be effected by mobile troops far out in Sinai. The divisions were withdrawn to prepare for deployment to France; the newly formed 4th and 5th Divisions relieved them, in part to keep them away from Cairo until they themselves were withdrawn for the Western Front 16.

Anzac

The landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 was, following earlier more ambitious ideas of taking Constantinople after brushing aside minor opposition en route, more realistically concentrated on assisting the Navy to break through the Dardanelles bottleneck to clear the sea passage to the Black Sea and Russia 17. As the stalemate barely forward of the beaches was not foreseen, the supply and transport units of 1st and NZ & A Divisions were loaded on the sea transports and stood off the landing beaches, waiting for the call to land in support of the drive inland. This did not eventuate, and in consequence the supply elements went ashore and the transport returned to Alexandria to be used as base transport 18. From this it had two notable breaks. The first was being reloaded into transport ships and sent forward ready for disembarkation to support the planned breakout in the Gallipoli August offensive, with a result no different than the first attempt; the second was the Western Frontier Force expedition described earlier. In addition, as a minor diversion, some drivers tried to break the stalemate on their own initiative as stowaways with reinforcement drafts to join their comrades at the front. The stay-behind element in Egypt from 1st, NZ & A, and subsequently 2nd Divisions amounted to 5,000 men, 12,000 horses and 1,200 wagons, including those of unit transport 19. Here they remained until the December withdrawal from Anzac, when they rejoined the evacuated divisions.

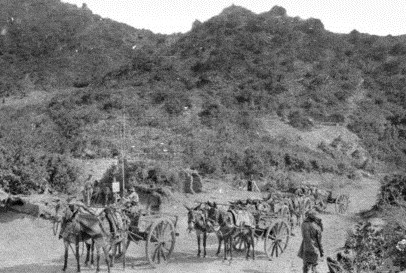

The AASC commitment on Anzac was essentially one of supply. The transport effort in a steep, roadless area was handled by the Indian Army Mule Cart Corps with 200 carts, some 5 Coy drivers to help work the mules, carrying parties from the combat units, and water pipeline; and a small wagon contingent from 3 Coy accompanied 2nd Brigade on its ill-fated Krithia assault at Helles. A Zion Mule Corps detachment of Russian Jewish refugees with 250 pack mules, failing to reproduce at Anzac the performance which had made the corps welcome at the Cape Helles front, was returned to Alexandria for disbandment 20. Later in the campaign a light railway was established, to be operated by 1st Tramway Detachment from 11 Coy, but its completion was pre-empted by the evacuation of the force. In consequence, the AASC task resolved itself to the operation of supply and ammunition depots, the distribution of water, and offshore the provision of fresh bread and meat.

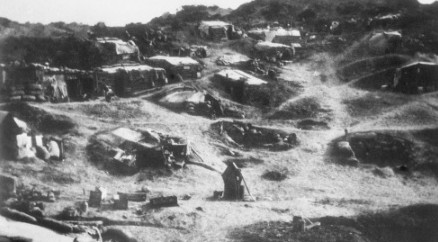

Initially, because of the narrowness of the area held – a maximum of 1.5 km from the beach – Anzac was regarded for logistics purposes as combat zone, with the lines of communication ending at delivery to the beach. This obvious and sensible demarcation in such a narrow and congested area became a bone of contention, with Anzac Corps insisting that lines of communication troops should take over the supply depots on the beach, and that divisional supply should operate forward from those depots. The Mediterranean Expeditionary Force staff eventually caved in to this importuning and cavilling, with the instant and inevitable result that when a Reserve Supply Depot was established to manage the beach stocks, divisional depots reopened beside them, and later brigade depots 21, introducing further manpower, handling, accounting and congestion. Again the bureaucratic mind substitutes rote learning for thought and practicality, and seeks to pass responsibility and any resultant blame for problems by involving another echelon.

The initial landings had built up by 1 May to 1 DUS from 11 Coy, 1 Div Train less transport but augmented by the Ammunition Section of 8 Coy (1 Div Amm Park), and NZ & A Div Train less transport, having initial strengths of 14, I55 and 83 respectively. When the later Light Horse Brigade reinforcement units and 2nd Division arrived on the peninsula they were accompanied by the supplies and some transport elements from their trains – 5, 6, 7, 14, 15, 16 and 17 Coys. The target stockholding was seven days rations and forage plus 3.3 million rounds of small arms ammunition and 4,300 shells, seven days reserve being held in the ships offshore. By 30 April Anzac Beach was congested with supplies, forage, ammunition and stores, so a second depot was opened 800 metres to the south at Brighton Beach. By mid-July stocks were 23 days rations and two days fuel for 25,000 men, and 5 days grain and 1 day of hay for 1,000 animals; by early November, with an additional division, they were at 32 days rations for 45,000 men and 10 days forage for 2,500 animals, much of which was lost in the evacuation a month later. Yet all through the period, water supply was precarious, with the local wells unable to cope, a distillation unit damaged by shellfire and ineffective, and any interruption or losses to imported water precipitating a crisis 22. The logic in these quite uneven stocks is as totally lacking as was the decision to introduce an extra echelon of depots into the beach area, and was partly a product of that same move. Notwithstanding the influences of winter weather, the U-boat threat and the emerging problems at Kut, there was a supply base at Mudros on Lemnos less than 100 km away and the advanced base at Imbros 24 krn away, with nightly delivery of supplies. A requirement for more than seven days is difficult to fathom, particularly when the water supply was a daily hand to mouth affair: men die of thirst long before they die of hunger.

After early use of some donkey transport with Greek drivers for water carrying, supplemented by Indian Mule Cart Corps mules and hand carrying, the donkeys were released by 1 May when the Indian carts began to arrive. To minimise the effects of observed artillery fire, the majority of discharge of stores was conducted at night, with lighters unloaded at piers onto the mule carts for movement to the depots. From these depots brigades drew rations and moved them by mule or carrying party to brigade depots, from which battalions drew and distributed to companies. Following an initial policy of issues on verbal demands, an ordered system was established to ensure a fair apportionment of resources, a reasonable system of accountability and a proper system of stock control and replenishment. The Ammunition Section of 8 Coy operated the ammunition dumps and 11 Coy took over the barge unloading responsibility at the end of June, building the three large reserve ration dumps over the next three weeks for the planned August offensive. After the failure of that offensive, when an extended winter stay was anticipated, it was decided to use Suvla Bay as an all-weather port, so half the unit began to build a light railway along the shore from Anzac to Suvla. Five kilometres were completed by time of the evacuation, and this was progressively put to use in distributing supplies, ammunition and engineer stores from piers to dumps 23.

Fresh rations were less than satisfactory. 1 Fd Bchy was at Lemnos with a 1 Fd Bky detachment, supplying the base there with fresh food. For the Gallipoli divisions, frozen meat was forwarded from a freezer ship at Imbros. The condition of the meat, after exposure to sun and flies and passing through so many echelons to get to the soldiers, was a cause of complaint and adverse medical advice which resulted in a defeatist suspension of issue during the hot months. Senior Medical Officer of NZ & A Div Col N. Manders hit the nail on the head in proposing better handling rather than cessation of supply but his voice was not heard amongst those of the excuse-makers or by commanders and staff who failed to demand from their supporting services how they were going to solve problems rather than reasons why they could not. Bread supply was delayed as 1 Fd Bky cooled its heels at Lemnos from March until moved to Imbros at the end of May. Then it was allowed to begin supplying fresh bread to the Anzac Corps from 9 June on the basis of an issue to half of the Corps each day, the half issue being excused by the Staff as resulting from transport limitations 24. These deficiencies and those of the over-sufficiency of hard rations and the undersupply of water show a lack of appreciation, energy and application to solve problems which were fixed elsewhere under equally difficult conditions, choosing instead the accumulation of 'easy' commodities to no valid purpose. This substitution of volume for quality does little credit to the supervising staff; just where the fault originated is unclear, but it was basically within the Anzac Corps and responsibility must be carried at each level at which remedial action was not effected. The victim was, of course, the fighting soldier who had the inadequacy of food and water to add to the privations and strain of his life in the trenches.

If the supply system lacked competent guiding hands, the AASC soldiers at least were up to scratch, living and operating on the beaches and its fringes, exposed to harassing shellfire and working through it, sharing many but not all of the dangers and privations of the combat troops. Indeed, they are reported to have made a fetish of ignoring shellfire to prove that point; Pte Ted Heaps of 11 Coy reported in his diary 25:

JuIy 29-August 1: It is terrible to see the poor chaps cut to pieces with shrapnel shells which is an everyday occurrence. The Infantry say it is safer in the trenches than on the beach; a lot won't come out of the trenches. I can tell you the beach and this gully, Anzac, is perfect hell ... The death toll on the beach and around our hill and gully is awful, the average is about 30 killed and wounded every day, so it shows you what a time we get.

Their efforts were well in keeping with the traditions which the Corps was building up. It is unfortunate that the experience, imagination and drive of the Supplies and Transport and General Staffs, both on and behind Anzac, were so limited as to restrict the efforts of the AASC units to less than they were capable of producing. Proving their full capacity came in the later campaigns.

Palestine and Syria

After the decision to abandon the Suez defence line in favour of mobile defence of Sinai, the defence of Egypt merges with what became the Palestine Campaign. A corollary to any military force seeking a forward defensible line is an ongoing creep forward: the 1915 line behind the Canal a year later became a line in front of the Canal, quickly followed by the concept of defence at Rafa and possibly El Arish 26. To go that far brought contact with Gaza, and the possibility of taking that line was given substance by the possession of sufficient troops to make it feasible; after that, Palestine lay open. So a defensive plan to economise in troops became a new front which absorbed increasing resources.

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force established a supply and transport system which grew progressively into a Supply and Transport Directorate with forward echelon in Palestine; a series of main supply depots at Alexandria, Cairo, Port Said, Kantara and Suez, supported by a frozen meat depot, dairy farm, fat factory and five compressed forage factories; supply depots progressively forward following the advance plus field bakeries and butcheries; base mechanical transport depot with heavy repair workshop and stores at Alexandria, advanced MT sub-depots at Cairo, Kantara, Rafa, Ludd; a series of area MT companies at each depot, sea and rail terminal; motor ambulance convoys, MT petrol companies and divisional ammunition sub-parks; MT companies attached to each corps; a Camel Transport Corps with depots at Cairo and Kantara, and 20 camel transport companies plus four donkey transport companies in forward support; and a base horse transport depot at Kantara, advanced depot at Ludd, and horse transport companies in rear and forward base areas 27.

The need to manage the large number of horses left out of battle from the then seemingly endless Gallipoli campaign led to the raising and despatch from Australia of Nos 1 and 2 Remount Units, each of four squadrons, which arrived in Egypt in December 1915 and opened two depots at Maadi. However the British base command had already begun to form an Egyptian remount system as a means of economising on both cost and military manpower, so these units were reduced and consolidated into Aust Remount Section of four squadrons in March 1916 as part of the AIF reorganisation and dispersal to the Western Front; it was further reduced to two squadrons in September and renamed Aust Remount Depot. The Depot was established at Kantara but moved to Moascar in August 1917 and an Advanced Remount Section subsequently followed operations to Ludd 28. The work of the unit is adequately summarised by one of the squadron commanders Maj A.B. Paterson 29:

We had fifty thousand horses and about ten thousand mules through the depot, in lots of a couple of thousand at a time. All these horses and mules had to be fed three times and watered twice every day; groomed thoroughly; the manure carted away and burnt, and each animal had to be exercised every day, including Sundays and holidays. His Majesty's Methusaliers had a perpetual motion job.

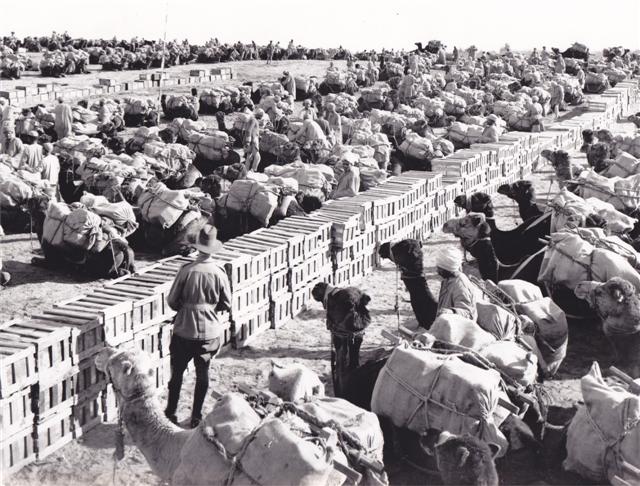

As operations developed in Sinai, the desert conditions precluded the use of wheeled transport and, with the initial plan of operating only in Sinai, the light horse brigade trains (5, 6, 12 Coys) were disbanded, the transport elements swallowed up in the trains going to France. The remainder was constituted as brigade supply sections for 1st, 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Brigades of Anzac Mounted Division. A rail and water pipeline was constructed following the advance, with camel trains operating forward of railhead to the brigade supply sections. There was a difficulty in organising the forward movement from railhead so the brigade sections were pirated to form a railhead section to break into brigade lots for forward move by camel train. These camels were from the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps which had been formed from local civilians in December 1915 in anticipation of the future need, but as NCOs were not available, they were obtained from the AASC and other AIF units then in Egypt. Of these 49 were eventually commissioned and six became company commanders, so the Anzac, and later Australian Mounted Divisions had a strong national component in their supporting camel transports 30.

The drain on the brigade supply sections caused enough problems to gain authorisation for formation of 26 and 27 DUS to take over the railhead duties in September 1916, but once Palestine was reached, wheeled transport was again feasible. Divisional trains were raised for Anzac Mounted Division and the newly formed Australian Mounted Division at the AASC Training Depot at Moascar in August 1917, their wagons being transported across Sinai by rail. These Divisional Trains were considered to be experimental as it was widely considered that horse transport would not be able to keep up with mounted formations, but in the absence of sufficient motor vehicles the expedient had to be tried. Anzac Mtd Div Train comprised 32, 33 and 34 Coys and 5 Coy NZASC, Aust Mtd Div Train 35, 36, 37 and 38 Coys, with 26 and 27 DUS now allotted one to each division. From thereon the general system was for British ASC MT companies or camel Transport companies, depending on the going, to deliver from railhead or port dumps forward to the Depot Units of Supply at replenishment points, from whence the horse transport of the divisional train distributed to the brigades and to divisional units. However this was often changed by allotting camels to brigades where the wheels could not cope. As the force moved north through Palestine and Syria, the composition of support changed – in late 1917 Desert Mounted Corps had L, H and N Coys totalling 6,000 camels and no lorries in convoy support; a year later it was B, M and part A Coy of 2,600 camels and 256 lorries of British ASC MT companies 31.

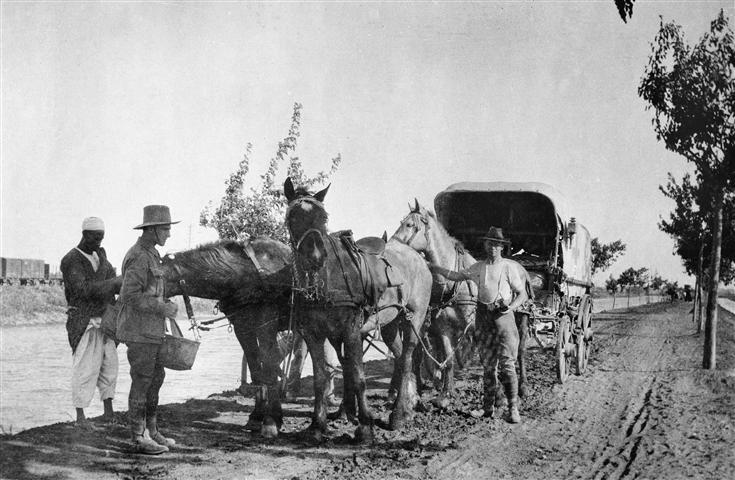

While the Brigade sections, DUS and camels had served Anzac Mounted Division and the two Australian brigades of Imperial Mounted Division well enough in the Sinai operations and static situation in front of Gaza, the plans for envelopment from Beersheba and subsequent break north required a support system to match the expected movement of the regiments. When the unavoidability of horse transport trains was accepted, and a decision was made to hive off Australian Mounted Division from Imperial Mounted Division shortly before the third Gaza offensive, Anzac and Aust Mtd Div Trains were hastily assembled from the Brigade Sections, other units and the Training Centre at Moascar. Australian drivers were rationed to one per wagon, with two companies of the Egyptian Army allotted to each Train to man the second driver positions, and mostly mules rather than horses were provided for the four-horse wagons. After a scant two weeks training for drivers and animals the companies were deployed forward to Rafa and Khan Yunis for their final training and to ease into routine support duties. The original prejudice against the mules was replaced by such a growing appreciation of their performance and endurance that whenever horses were issued as replacements, the units exchanged them for mules with any later arriving units before they came to realise the relative merits 32.

October brought the beginning of the third battle of Gaza, which sent the Desert Mounted Corps to the Beersheba flank. The Trains ferried supplies from the Advanced Supply Depot at Gamli to forward dumps at Esani, and from there delivered forward in support of the assaulting troops. The success of the attack left 30,000 animals competing for water from the damaged wells, and the Trains were withdrawn back to operate forward from the railhead at Karm. After the fall of Gaza the Trains moved with their divisions to the coast for the pursuit north through the Plain of Philistia: the viability of the wagon transport in support of mounted troops was now to meet its first real test. Initially Desert Mounted Corps Head-Quarters did not believe that the Trains could cope and detached them to directly under its control, using the horsed companies as part of a composite effort with lorries and camels forward of the Advanced Supply Depot at Julius where 26 and 27 DUS operated. The need for close support reasserted itself and the Trains, operating forward of lorry-head at Ramleh, followed their divisions tenaciously, often operating 20-hour days, covering 400 km during the pursuit to Jaffa and the Judean hills, until the rains brought mounted operations to a halt.

From hereon the Trains had the difficult task of operating in the hill country over poor roads and tracks which were barely passable in the wet conditions. Convoys were restricted to packets of six to facilitate passing on narrow roads and to minimise targets for air attack; CO of Anzac Mtd Div Train Lt-Col N.B. Loveridge recorded earlier 'we had a Hotchkiss gun with us ... so the ASC opened at him. He went away and came back and gave us a real dust up'. With the onset of winter, motor transport was grounded and camels limited in operation, the additional distances fell on the divisional trains: the effects of cold, wet and steep rocky grades so severe on the mules that each company had to be spelled in turn every third day. Life became temporarily easier after the fall of Jerusalem on 9 December, the divisions being withdrawn in the new year to the sand hills of Belah for rest and training, although the Trains still had to keep up their daily resupply routine, but at least away from the hills and boggy black soil plains of Palestine 33.

The next major activity commenced at the end of March 1918, using Jericho as a base for operations in the Jordan Valley and eastwards. It was the beginning of a long hot summer in which heat, dust, insects and malaria took a severe toll on the whole force, keeping both unit doctors and veterinarians endlessly busy. First, Australian Mounted Division bore the brunt of this until mid-June, when relieved by Anzac Mounted Division. That Division became part of a larger Chaytor Force in which Loveridge became CO ASC, having under command, as well as his own Train, 29 Indian and 235 Inf Bde Trains, M Coy Camel Tpt Corps, 357 and 1040 MT Coys, tractors and first line wagons.

These operations in the Valley and Mountains of Moab extended to Es Salt and Amman from September until the end of October. Aust Mtd Div Train was sent to Bethlehem to repair the ravages on men, animals and wagons, until recommitted to the Valley a month later, however this time it was for only two weeks as, at the end of the month, the Division was pulled out to Ludd in preparation for the attack at Megiddo in September. The break out in that battle meant a period of rapid movement in following the cavalry advance through Nazareth and then into Syria, the companies being replenished by motor transport and pressing on behind the brigades 34.

By October 1918 Turkish resistance was crumbling, prisoners and booty were beginning to pile up. Anzac Mounted Division's deliveries of forage, food and ammunition to the brigades in trans-Jordan became interspersed with collecting and evacuating sick and wounded prisoners and captured materiel. Aust Mtd Div Train was following up its Division's dash to Damascus, then Aleppo, with 35 Coy taking its own share of prisoners en route; even with the speed of the advance and congested routes, CO Lt-Col H.A. Maunder claimed that 'on no day did the Train lose touch with the division' 35.

Official Australian historian Gullet ascribes some credit for the success of the AASC to its direction by Desert Mounted Corps DA&QMG Brig-Gen E.F. Trew, AQMG Lt-CoI W.P. Farr and ADS&T Lt-Col W. Stansfield 'the Queensland magician of supply and transport'. This was a far cry from the inertia and defeatism of command and staff at Gallipoli, and one which allowed the AASC to achieve its full potential. Stansfield had been at Gallipoli in command of the 5 Coy detachment, and was well enough aware of the problems and failure of his superiors to confront them face on. As subsequent OC AASC Egypt then ADST Desert Mounted Corps he ensured that mistakes were not repeated, that problems were for solving, and that planning, and drive in implementing plans and overcoming obstacles, replaced finding problems but no answers. The success of the AASC staff, commanders and of the divisional trains, their companies and their members is commented on in W.T. Massey’s account of The Great Drive in Philistia, that:

During that diagonal march across the maritime plain I heard the infantry officers remark that the Australians always seemed to have their supplies up with them. I do not think the supplies were always there, but they generally were not far behind, and if resource and energy could work miracles the Australian supply officers deserve the credit for them.

The Aust Mtd Div Train account is more specific: ‘not one day did the Division go without a ration' 36.

While it was not the responsibility of British historian Massey to identify Australian units involved, Australian historian Gullett had that responsibility, but omits, throughout his volume on the campaign, naming the units although he invariably does this for the light horse, artillery and infantry units and would have considered it a gross discourtesy not to have done so; but he apparently felt no sense of short selling the divisional trains and companies in saying ‘transport came up’, 'Australian Army Service' and 'supply troops'. He even quite specifically discounts Massey's 'resource and energy', choosing instead to romanticise the performance with the platitude 'the efficiency of the service was due to the deep admiration and affection in which the supply troops held the light horsemen in the firing line' 37. This view is patronising to say the least. Perhaps it did not occur to him that the members of the AASC companies wanted to do a good job, took pride in doing it and took pride in their unit in just the same sense as did the light horsemen. They were as much a part of the organisation as were the regiments and in their own way turned in an equally sterling performance. There seems to be a mental paralysis in military historians in handling the logistics services and recognising that they are comprised of named units and soldiers doing an essential job, often facing hardships equal to and sometimes exceeding those of the fighting units. The commanders of the fighting formations did not lack this understanding and had no such inhibitions in recognising it in the form of the numerous performance and bravery citations and decorations awarded to the units, officers and soldiers of the AASC, both in this theatre and the Western Front, as recorded in Appendix 2.

Western Front

After a minimum of training in the Egyptian base, 1st and 2nd Divisions were moved to France to meet an urgent call of the upcoming Somme offensive, arriving at the Armentieres front in March. Here the two divisional AASCs were rejoined by 1st Division's erstwhile 8 and 9 Coys – the motorised Supply Column and Ammunition Sub-Park. In England, these units had been reequipped with Peerless 3 ton and Daimler 30 cwt lorries for standardisation and reformed as 301 and 300 Coys ASC, being dispatched to France in July 1915 for duty as 17 Div Amm Park and 17 Div Sup Col respectively, until again reorganised as part of the British restructuring to economise in supplies and transport units in the static operations which had developed on the Western Front. They became corps units allocated as 17 Div Amm Sub-Park and a reduced 17 Div Sup Col; the surplus members from each were incorporated into a third unit 23 Div Amm Sub-Park. However, with the arrival of the Australian divisions, those units were reallotted as 1 Div Amm Sub-Park, 1 Div Sup Col and 2 Div Amm Sub-Park; a British ASC unit was allotted as 2 Div Sup CoI. Similarly 4th and 5th Divisions were supported by British ASC corps motorised units on arrival in France in June 1916, 4 Div Amm Sub-Park being Australianised within a month, the remainder waiting until the arrival of MT units from Australia in 1917. When 3rd Division, which arrived in England from Australia in July 1916, was finally released from its reinforcement role and joined the force in France in November, it brought its full complement of horse transport units, the motorised 3 Div Sup CoI raised in Australia, and 3 Div Amm Sub-Park cloned from the Supply Column and from reallocated manpower in England. There was also an ongoing drain on the motorised units as their talents were recognised, a large number of drivers and NCOs being commissioned into other areas: Light Horse, Artillery, Infantry, Machine Guns, Pioneers and Ordnance; Dvr H. Bateson became a commander in the Royal Navy, others joined the British ASC and other regiments; and a remarkable number became pilots, 36 in the Australian Flying Corps, 15 to the Royal Flying Corps and one to the Royal Naval Air Service 38.

The Australian divisions in the Western Front were, with the New Zealand Division which had been raised from the disbanded NZ and A Division, formed progressively as they arrived into I Anzac Corps comprising 1st, 2nd and NZ Divisions and joined in October by 5th Division; and II Anzac Corps comprising 4th and 5th Divisions until 5th left for I Anzac Corps, being replaced by 3rd Division in November. This arrangement remained basically unaltered until late 1917, although divisions were employed in other corps for particular immediate tasks. The Anzac Corps were alternatively coded as K Corps and Y Corps, under which title they and their corps AASC units were commonly known, from 1916 to December 1917, when the five divisions were concentrated into I Anzac Corps, the NZ Division joining XXII Corps; on 24 December I Anzac Corps was given the Christmas present of being renamed 1st Australian Corps 39. Together with these changes in grouping went the AASC units, which were also twice reorganised in line with the British Army search for economy of support units to release men and materiel to make good the fearful losses in the front line. The first was withdrawal and consolidation of divisional supply and ammunition motorised units into corps parks and columns which had affected 8 and 9 Coys; the second rationalisation disposed of the reserve columns which released 10 Coy to help form the new divisional trains, and combined the myriads of small depot units of supply into sensible corps supply companies which latter the AIF studiously ignored, preferring to maintain the direct links between brigades and their 'own' depot in the rear 40. This unique holding out from an otherwise firm policy of mirroring all British tactical and administrative organisation, although a minor and therefore tolerable aberration, was an early demonstration of a recurring shibboleth of Australian middle level command – that it is better to have your own puddle than access to a big pool: the logic of breadth and depth of support of a pool, and economies of scale were usually lost in the urge for possession and false idea that only possession can guarantee response.

An intermediate transition from the beginning of 1917 established ASC headquarters to control each corps' MT, including artillery ammunition columns and siege park, and field ambulances. Motor transport resources were now theoretically pooled, though each formation in practice had a sub-unit dedicated to a single commodity regardless of the fluctuating workload resulting from divisional locations and employment at a particular time, so a final reorganisation was effected in March 1918 when corps motorised ammunition parks and supply columns were consolidated into all-purpose columns. The Australian columns and sub-parks were now more effectively pooled into 1 Aust Corps MT Col comprising a headquarters and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 MT Coys to provide all transport between railhead and divisional trains: one company for direct support of each division, with 6 Coy a reduced one for corps troops. At the railhead was Aust Railhead Supply Section to manage transfer of corps supplies to the MT Column, and at Southampton and Harfleur, the Australian Sea Transport Service ensured AIF stores were moved, recognised and directed to the correct destination. The divisions retained their trains, with their direct support Depot Units of Supply at the railhead, tramway supply distribution points, replenishment points or forward dumps; however all 25 of the depot units could not be found such employment in the static operations and were lent for extended periods to work for British units – 1st Army Purchasing Board (1 DUS), scattered throughout 4 BSD (5 DUS) and running 3 BSD forage depot (19 DUS). The field bakery and butchery units allotted to each division were employed in civil facilities or constructed static installations at Rouen to achieve optimum operating conditions 41.

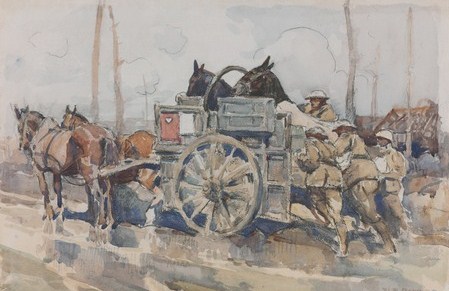

As each divisional train had arrived in France in the spring of 1916, it drew equipment and horses from the British depots and moved into the line. The basic resupply system was for divisional supply columns to draw from railhead and deliver to a refilling point into the custody of the divisional depot units of supply, from which the divisional train companies would collect and distribute to the brigade/divisional troops which they supported. This intermediate point was frequently necessary as the daily turnaround distance of the horsed train from the unit QM stores was limited, often even more so by enemy ground and air action, poor roads and weather. These latter factors affected the motor transport as well: in extreme conditions or when roads were closed to motor vehicles for maintenance, snow, thaw or rain, the motor transport was laid up. When this happened the divisional train wagons had to make the turnaround from rail to units, resulting in heavy casualties to the draught horses affected not only by the greater distance but also the constant work in slushy conditions; and to make the equation worse, the drivers were then so overcommitted to time on the road they were unable to erect shelters for the horses and drain the horse lines 42. While the motor transport provided an irreplaceable lift capacity under good conditions, its pre-multi axle drive performance meant that the horse and pack mule were indispensable to guarantee supply from the rear, and the only means of supplying the front.

The tasks of the trains and motorised columns were varied. The train companies had a basic obligation to carry baggage and resupply food, forage and water for the headquarters and units of the division, but their additional tasks were more numerous. The daily work sheets of the companies show a continuing variety of general tasks from providing drivers for formation headquarters and field ambulances to carting roadmaking materials, operating snow ploughs, using sledges to evacuate casualties through the mud, providing transport for postal deliveries, repairing unit equipment, and operating ad hoc pack transport units 43. The supply columns and ammunition sub-parks, in addition to their basic tasks, hauled lumber, road metal, ordnance and postal cargo, petrol, quicklime, rails and medical comforts, as well as emergency mass medical evacuation and incidentally filling in as medical assistants at dressing stations, 1 Div Amm Sub-Park even publishing the AIF newspaper Rising Sun, later renamed Aussie 44. The units on the Western Front were involved in the following actions 45:

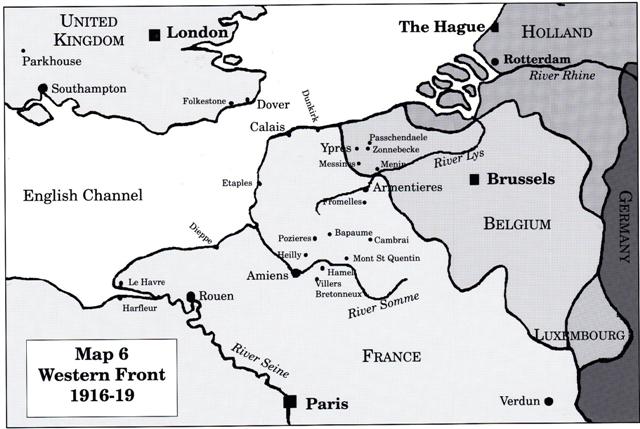

Map 6: Western Front 1915-1919

Phases of Operations |

Periods of Operations |

Year |

Activities and Battles Supported |

Divisional Trains (1) |

MT Coys(2) |

| British Army Support | Jun-Apr | 1915-16 | Somme | 8, 9 | |

Armentieres |

Apr-Jul |

1916 |

Induction |

1, 2, 4 |

1, 2, 4 |

Somme |

Jul-Nov Jul Sep |

1916 |

Offensive Pozieres, Moquet Fm |

1, 2, 4 |

1, 2, 4 |

Ypres Salient |

Sep-Oct |

1916 |

Holding line |

1, 2, 4, 5 |

1, 2, 4 |

Somme Winter |

Nov-Feb |

1916-17 |

Holding line |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

1, 2, 3, 4 |

German Withdrawal |

Feb-May |

1917 |

Offensive |

. |

. |

Battle of Messines |

May-Jul |

1917 |

Offensive |

3, 4 |

3 |

3rd Battle of Ypres |

May-Nov Oct |

1917 |

Offensive |

. |

. |

Battle of Cambrai |

Nov-Jan |

1917-18 |

Reserve |

4 |

4 |

Flanders Winter |

Nov-Apr |

1917-18 |

Holding line |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

German Offensive |

Mar-Jul Mar-Jul |

1918 |

Defence-Offence Defence of Amiens |

2, 3, 4,5 |

2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

Final Offensive |

Aug-Oct |

1918 |

Offensive Mont St Quentin |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

1-6 |

1. Includes the depot units of supply, field bakeries and butcheries attached to each. The several divisions were rotated into different parts of the line and so are shown in overlapping periods.

2. Until March 1918, numbers refer to divisional supply columns and ammunition sub-parks, thereafter to mechanical transport companies; further, until mid 1917, 1 and 3 refer to both 1 and 3 Div Sup Cols and 1 and 3 Amm Sub-Parks; 2 and 4 refer only to 2 and 4 Amm Sub -Parks as those divisions were supported by British ASC Sup Cols, as was 5 Div for both Sup Col and Amm Sub-Park, which are consequently not listed.

An adequate description of the actions needs a separate history for each of the units, which is properly the task of unit historians. Of course there is much which has an inevitable apparent sameness as the unending routine of daily resupply and general transport tasks repeats itself over three years. To the men there was much of sameness but also the daily problems of operating in an environment which was basically hostile to the achievement of their tasks – getting supplies forward meant overcoming not only the natural ones of difficult going but also keeping control under artillery and machine gun fire, air attack and gas attack. And when the daily tasks were over, the vehicles or wagons and horses demanded constant attention. Inspecting British officers were less than enthusiastic about the spit and polish of driver, wagon and lorry, but noted the good condition of the horses; however these horses were often the indirect cause of their drivers becoming casualties as they had to stand at the animals' heads under shellfire to quiet and control them 46. But both horse and motorised units could keep going only as long as unit veterinary officer, remount depot and veterinary hospitals kept draught and riding animals in health, and artificers kept lorries, wagons and harness repaired to a taskworthy state. In the usually poor working conditions prevailing, their task was as exacting and difficult as that of the drivers. And when the divisions came out of the line for rest, the work of supply, transport and repair did not stop but had to continue, albeit under less arduous conditions, as the fighting units rested and retrained.

Western Front Support Activities

The following selections from the war diaries of the companies give an indication of the range of experiences in operations and some explanation of the origin of the awards shown in Appendix 2 47:

1 Div Sup Col – Rubempre, 27 July 1916

Lorries from this Unit were required to proceed to Railhead by 3am, load and deliver supplies and afterwards proceed to rendezvous for duty in connection with wounded. The Medical Officer at the Tramway Dump Dressing Station had only a small staff so that the lorry drivers were able to render valuable aid in connection with the handling of the wounded in addition to giving the necessary attention to their vehicles.

2 Div Train – Senlis, July 1916

29 July: Detail of 20 wagons required for evacuation of wounded. Directed to report to CO 5th Field Ambulance.

6 August: A letter received from 5th Field Ambulance warmly praised the work of the 12 GS wagons under Lt Gravely evacuating wounded.

5 Div Train - Sailly, September 1916

13 September: During transport of trench material to front lines enemy opened fire with machine guns on wagons.

20 September: Coolness of Lt Franzini Charles 8th Bde Supply Officer in assisting civilian population with first aid, under shell fire, and with stopping a runaway wagon that had been frightened by shellfire.2 Div Train – Albert, 5 November 1916

Lt Cox was detailed to take charge of 40 horses for ambulance sledge work at Thistle Dump.

1 Corps Amm Park – Heilly, December 1916

Lorries on daily engineer work December: 148, 146, 134, 141, 116, 136, … (etc)

1 Div Train – Ville, December 1916

1-6 December: Transport drivers have not got the time to do the fatigue work which is necessary to keep the horse lines in a satisfactory state ... all transport fully employed and have been for the last two months.

7-30 December: Many men and horses evacuated which would have undoubtedly been avoided if the proper accommodation had been attended to at once.4 Amm Sub-Park – Albert, February 1917

Thaw precautions were adopted on the 18th and all lorry details cancelled ... Lorries recommenced running on the 25th; speed not to exceed 5 miles per hour.

3 Div Sup Col – Messines, March-May 1917

Unit employed on road work in advanced area frequently under shellfire. Lt Dawson was selected early in May to superintend the whole of the transport working in the advanced area around Niepple, Neuve Eglise and Wulvingham. This change resulted in the work of roadmaking being pushed on in preparation for the June offensive which culminated in the capture of Messines Ridge.

4 Div Train – Messines, 31 May 17

Prior to the attack an incident occurred in daylight, a convoy when off-loading road metal was violently shelled and an 18 pr dump was burning in the vicinity. The infantry sought cover and left the Drivers with an officer to extricate themselves on a narrow road impossible to turn in. The drivers, assisted by the Officer, with great coolness unhooked and removed the horses, rescued one from a shell hole and got away with one horse wounded only.

SMTO 7 Anzac Corps – Hoograaf, September 1917

1,200-1,400 lorries on charge, tasks supplies, ammunition, personnel, stone, timber, miscellaneous.

1 Div Train – Dickebusch, 17 September 1917

Lt F.L. Smith & CSM Lane of the Divisional Train have been employed on pack convoy duties, transporting water and engineer Stores to forward dumps – and up to date have performed their duties with few casualties only, although the ground is pitted with shell holes and the ground swept by Enemy's artillery and machine gun fire.

16 Coy 2 Div Train – Reninghelst, 30 September 1917

When proceeding from Hellfire Corner to Bellewarde Ridge, owing to the dense fog and enemy fire 5 vehicles were precipitated into the ditch alongside the road. The fire became increasingly severe but the courage and initiative displayed by Sgt Finck enabled the wagons to be extricated and the load duly delivered. The road was under heavy fire the whole time, and this convoy the only transport which had not abandoned it.

20 Coy 2 Div Train – Zonnebecke, November 1917

This day was one of our worst experienced, the enemy shelled the track from Westhoek Ridge to the North side of Anzac Ridge continually, putting in a number of gas shells; it was one of the greatest tests our drivers have been through, the road being continually blown up by shells ... making the road quite impassable, but quite heedless of their own dangers, the Drivers would dismount and stand to their horses heads while the road was being repaired. Our NCOs played a great part in this work, collecting what men they could, would at once lay sleepers across the shell holes, then proceed to the next damaged part.

3 Div Train – Ypres, September 1917

Each brigade formed its own Brigade Pack Transport ... an officer was made available for the purpose of taking charge of the Divisional Pack Troop.

4 Div Train – Peronne, 17 December L917

2Lt F. Cawley MC was awarded the Military Cross for his services as OC Convoy on road work in the vicinity of Passchendaele Ridge. This officer was occupied from 7/10/17 to 23/10/17 in Forward Area subject to heavy artillery fire.

4 Div Train – Merris Bailleul, 24 March 1918

March of train transport south to Somme 24-27 March – 79 miles at 1 mile per hour for the whole march.

2 Div Train – Beaucourt, 21 April 1918

Anti-aircraft defensive arrangements have been made as follows: one Hotchkiss gun is mounted and manned by each company of this train.

1 Div Train – Lys, JuIy 1918

The transport duties for the month have been heavy – but the horses continue to keep in excellent condition. The transport in the forward area has for the month resulted in 4 men and 5 horses being wounded and two horses killed. Health of men is good, discipline good and spirit of men excellent.

5 Div Train – Camon Gardens, April-September 1918

On entering the district in early April it was noticed that the gardens, some of the finest in this part of France, had been evacuated in toto by the inhabitants and that vegetables already planted were going to seed and waste ... From May 8th to 14th September 151 tons of fresh vegetables have been cleared from the Gardens on account of requisitions and our own cultivation.

2 Div Train – Mont St Quentin, 25 August-4 September 1918

It was clearly indicated that no lorries could be made available owing to the pressing need for these vehicles for other work, and that the Train would have to perform the work of the Supply Column in addition to its normal and proper duties ... The distances travelled by the Horse Transport varied considerably, in some cases being 15 miles for the double journey, in others 18 miles. These distances would have been considerably increased had the weather not been fine and dry, thus enabling the cross country tracks to be made use of. In mobile warfare of any duration this substitution of Horse for Mechanical Transport between railhead and Refilling Point could not be maintained, but in this instance the period was not long enough nor the daily advance great enough to do more than strain our Transport resources.

4 Div Train – Villers-Bretonneux, 8 August 1918

One party, under Lt Vassy from 14th Company, working on the left of our advance, carrying engineer stores, arrived at the 'Green Line' and had to wait with a Machine Gun Company in action until our boys hopped over and took the 'Red Line' ... Shelling was lively at this spot. The wagons pushed on with our infantry …

The flanking party on our right consisted of the 7th and 26th Companies also carrying Engineer stores, and they, in turn, had to halt until the advance was continued from the 'Green Line'. At that period they were in advance of our Field Artillery in action, who wanted to know what the hell the ASC was doing there ...

The night before all the Engineers and other stores were blown up with the Tanks, which were detailed for this duty, while standing parked in Villers-Bretonneux. At a late hour the CO was asked to supply twenty wagons to help replace this loss, as Engineer material was urgently wanted to accompany the advance on the morrow ... It was a long journey and one which called for courage and skill ... it adds another page to the history of this Train, to which, I am sure, you are proud to belong ... I like to think that when the Tanks fail the ASC can fill the breach, and what is most pleasing to me is the cheerful way you put up with the difficulties and hardship and carry on.Allen A. Holdsworth Lt-Col

Commanding 4th Aust Divisional Train

Aftermath

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 saw an end to immediate fighting on the Western Front, the Middle East fronts having already concluded with Turkey's surrender at the end of October. However the 'war to end wars' failed that test very quickly, with European countries fighting against the Reds in Poland and Russia until 1921, and against Turkey until 1923. Although the Australian forces were withdrawn from commitment to the occupation of Germany, they did not entirely escape involvement in some of the aftermath, AIF volunteers being involved in a limited but bitter action against the Bolsheviks in north Russia, supported by the RASC, and 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Brigades were also unfortunate to be committed to suppression of a political uprising in Egypt from March to May 1919, with 34 and 37 Coys reconstituted from partial disbandment to provide support 48. Also the AASC units remained committed to their support role after the ceasefires as, although ammunition expenditure collapsed, food, fuel and forage were in continuing demand and transport was at a premium. As the divisions in the Middle East and France were progressively repatriated through 1919, so the AASC units closed down their activities and followed. The last of the AASC units in Egypt was disbanded by the end of June 1919 and home by August; in Europe, although the main units were gone by then, the Sea Transport Service remained to the end, seeing off the last contingents of the AIF at the end of the year.

This baptism of the AASC had seen it grow from the training base in a militia army to a seasoned component of field armies in Europe and the Middle East. There was no question that, after initial problems where inexperience had hampered enthusiasm and after talent had replaced place men, it had become at least as effective as its equivalents in the professional armies of Europe, though its extension into base responsibilities had been curtailed by an obviously rational reliance on the British Army infrastructure. The AASC had met its obligations at an exemplary standard within this limitation; a fuller test was to come when the Australian forces fought their own war a quarter of a century later.

Footnotes

1. Bean vol I, p9, 21-4, 27-8.

3. Bean vol I, p28-9; Scott, p11.

6. MO 1/1914, 150/1919, 103/20; Scott, p197.

7. Scott, p212, 226, 286, 290-4, 397-400, 402-4, 43 -443, 452-3, 469; MacKenzie S.S. The Australians at Rabaul p23, 28; Broinowski Tasmania's War Record p3, 5-7.

8. CPP 1917-19 vol IV Proposals of the Government on Home Defence of Australia, p3.

9. Report upon the Department of Defence 1914-17 Part 1, p267-8, 27 4-6, 278; Long Final Campaigns p636.

10. MacKenzie, p1-2, 29,180-1; Scott, p197.

11. Commonwealth Military Journal January, July 1915, January 1916; Bean vol I, p109-112; AWM 224 MSS250.

12. Broinowski, p40-1; AWM 224 2 DRL 1160.

13. Bean vol I, p192; AWM MSS 245; Bean vol III, p14.

14. Bean vol II, p805-6 is at variance with the arrivals of the brigade trains in CMJ July 1915.

15. Bean vol I, p14-5; AWM 224 MSS 211.

16. Bean vol III, p22-5, 30-1; AWM 224 MSS 228.

17. Bean vol I, p192-3, and 200-1.

18. Bean vol II, p362-3; vol III, p14.

19. Bean vol II, p398 Note 18.

20. Beadon RASC p161, 165-6; AWM 224 MSS 218; Bean vol II, p363.

21. Broinowski, p41; Bean vol II, p352-3.

22. Bean vol I, p281; vol II, p347-9, 352, 359 Note 24, 847; AWM 224 MSS 218; Beadon RASC p172.

23. Beadon RASC p165-6; Bean vol II, p352-3, 361; AWM 224 MSS 228.

24. Broinowski, p32; Bean vol II, p364 and Notes 33-6.

25. Bean vol I, p547-8, 552; ‘Heaps Diary' Australian 24 April 1990.

26. Gullett H.S. Sinai and Palestine p50.

27. Badcock G.E. A History of the Transport Services of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force 1917-1918, Appendix II.28. AWM 224 MSS 471.

29. Paterson A.B. Happy Dispatches p178.

30. Badcock, p27-30, Appendix I; AWM 224 MSS 214.

31. AWM 224 MSS 212, 213, 214; Badcock, p152-3, 212.

33. AWM 224 2 DRL 1160; MSS 212, 213.

34. AWM 224 MSS 254; MSS 2 DRL 1160.

35. AWM 224 MSS 212, 254; Broinowski, p165-6.

36. Gullett, p451-2; Massey W.T. How Jerusalem Was Won p89; AWM 224 MSS 212.

39. Bean C.E.W. Anzac to Amiens p202, 219, 266, 349, 402.

40. Beadon, p128: cf Table 2; AWM 26 368/16.

41. AWM 25 721/30; AWM 26 292/8; AWM 224 MSS 229, 231, 236-7.

42. AWM 26 28/15, 55/17, 60/34, 79/24, 239/27, 124/20-22.

43. AWM 26 58/25, 98/4, 128/14, 239/27, 239/30, 248/33.

44. AWM 5 vol 100 17 December 1917; AWM 26 55/17, 79/24, 118/10, 128/13, 227/20, 369/4; Bean vol III, p955 note 23.

45. Bean vol III-VI, and, also Anzac to Amiens passim; Smith S. The Australian Campaigns in the Great War passim.

46. AWM 26 58/22, 79/24, 204/11, 239/27, 239/30, 248/33, 378/5; Bean vol III, p957.

47. In sequence: AWM 26: 55/17, 58/25, 79/24, 118/10, 124/20-21, 128/14, 159/1, 204/11, 227/20, 239/27, 248/33; AWM 5 vol 100 17 December 1917, AWM 26 248/36, 256/19, 413/1, 465/26, 566/4, 521/5, 551/15.