Chapter 3

War and Aftermath

Impact of World War 1

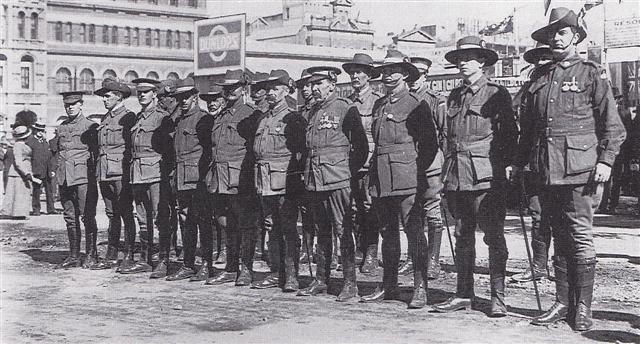

The outbreak of World War 1 brought home the reality of the nature of Australia's Army: the Australian Military Forces had been organised as a training militia to provide a substantial force for home defence against a regional threat seen to be posed by Japan. In consequence, the Australian Government's determination for the immediate despatch of two expeditionary forces to the South West Pacific and the war in Europe ran up against the twin barriers of the Defence Act prohibition on compulsory trainees being directed overseas, and the structure of the forces created to service the compulsory training scheme. The scattered units might have been readily regrouped into the divisional structure, with the majority of the compulsory trainees volunteering for overseas service as happened in Canada, but the effect of feeding the Militia from the ranks of the Senior Cadets had significantly changed its composition and experience levels. By 1914 the oldest compulsory trainee was 20: it would be another five years until the balance of 18-25 year olds was achieved, and in the meantime the voluntary soldiers had been discharged as their engagements expired. Raising of the two expeditionary forces was therefore based on volunteers from a broader spectrum of the community by age, experience and willingness. They included initially a high proportion with previous service in the Militia, rifle clubs, imperial service, the Boer War, and even some from the Soudan Contingent. The first force was designated Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force for the Pacific task, reflecting its joint and less formal organisation. The other and much greater destined for the European war was called the Australian Imperial Force in consonance with the Government's offer of a 'Force to be at complete disposal of the Home Government’ 1. It was raised on a combat establishment to match the forces it would be fighting alongside as opposed to the mixed-unit area groupings on which the Militia was organised.

Discounting the minor and soon run down component of the ANMEF, the Army thus became two armies, each with its own unit, training, administrative and promotion systems. The AIF grew to seven divisions in France and the Middle East, with an administrative and depot structure first in Egypt then in England, while the AMF remained in Australia as a home defence force, based on some standing units, but mainly Militia and Cadets of the still operating Kitchener area-system and rifle clubs, together with a staff for command, and a base structure for the recruitment, preparation, dispatch and rehabilitation of the AIF. The AMF component continued to expand with the progressive annual inputs from the Universal Training Senior Cadets, although manpower demands for the AIF progressively siphoned much of this strength away and stripped many of the officers and non commissioned officers whose presence was so necessary for effective training. But although this created a crisis resulting in 1917 amalgamations of mounted and infantry units of the AMF, the AASC units maintained their viability, supported by cadres of repatriated AIF members and the call up of mature age men in the 21-50 age bracket. In addition the camps which had been cancelled in 1916 were made up by trainees having to do additional periods in 1918 and 1919 2, all moves hard to divorce from the other pressures being used to encourage men to join the AIF before and after the failed conscription referendums. As a result of these measures, the organisations, including a renumbering of companies occasioned by the 1917 training brigade restructure, developed as follows 3:

District |

1917 |

1919 |

1920 |

1st |

1, 2, 3, 24 |

5, 17, 21, 23 |

1, 8, 17, 21, 23 |

2nd |

4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 25, 26 |

1, 2, 6, 7, 15, 19, 20, 24, 26, 27 |

2, 3, 7, 15, 19, 20, 24, 26, 27, 32, 33, 35 |

3rd |

12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 28, 30 |

3, 9, 10, 12, 18, 22, 28, 29, 30 |

4, 5, 9, 1O, 12, 13, 18, 22, 28, 29, 30, 36 |

4th |

19, 20, 31 |

14, 25, 31 |

6, 14, 25, 31 |

5th |

22 |

16 |

16 |

6th |

23 |

4 |

34 |

Raising the AIF meant that its AASC component had to face up to meeting the 1912-accepted liability of not only the horse drawn divisional train which matched the familiar brigade transport and supply columns, but also the motorised supply column and ammunition park plus the required field bakery, butchery and depot units of supply 4. Subsequently, each of these organisations had to be replicated for the 2nd Division in 1915, and the following year for two further divisions raised in Egypt and another in Australia for service on the Western Front. The one point of relief was the undertaking of the British Army to provide the infrastructure of supply and base depots and strategic transport in which the Force would operate, so obviating a drain on manpower which would have had serious repercussions on an already stretched force.

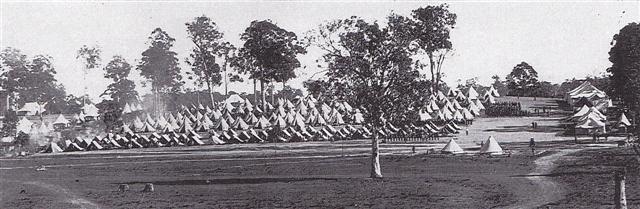

While the AMF AASC companies in Australia continued their training and supporting role for the home defence force, AIF training was essentially centred in the AIF training depots in Egypt, England and France. Preparation of reinforcements in Australia was rudimentary, many proceeding overseas in the earlier stages without having handled a rifle due to the inability of the Lithgow Small Arms Factory to meet the initial demand. The basic horse handling and related artificer skills available in the country meant that a reasonable technical proficiency in those areas could be maintained, so in both AMF and AIF horse transport units this was not a problem. Surprisingly, the low level of motor transport penetration in the civil community did not pose a problem in the raising and reinforcement of the AASC motorised units for the AIF. Such numbers offered that recruiters were able to pick and choose the most suitable, and the added ability to pick through the surplus of volunteers and rehabilitees from other arms overseas, together with the availability of British training facilities, allowed all motor drivers to be trained in England and France by 1917. Willingness of the United Kingdom to procure and on-sell the equipment solved the other part of the problem 5. The home units were relieved of any such problem: mechanisation of the AASC in Australia was two decades away.

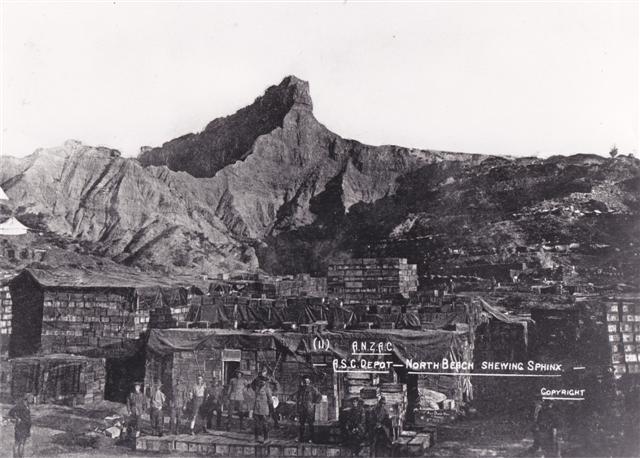

Provision of supplies, forage and ammunition was also undertaken by the British Government on a repayment basis. This eliminated a vast array of technical and financial services and units which would otherwise have been needed in Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. While no direct comparison can be made with any accuracy, some rough indication is given by the relativity of the peak 93 units and 9,735 AASC members of the AIF compared to the 612 units and 50,000 strength of the AASC in World War 2 6, where the South West Pacific theatre was supported from the Australian base. On the home front, the AASC had to support training of the AIF and AMF, plus the comparatively minor ANMEF, which latter was within the capacity of the AD of S&T of 2nd Military District. The effect was that of a large transitory population of AIF recruit drafts and Militia camps which kept a continuing pressure but no great operational drama on the supply and transport staffs and units within the military districts. The real dramas of supply and of transport resided with the war office and Army staffs in Europe and the Middle East. Australia's contribution in that area was a basic one as bulk supplier of primary and some secondary products, and of horses 7.

Had the expansion of the AASC been undertaken on the base of the fully implemented Kitchener plan, it would have been both a natural progression and a natural use of the forces so provided. But the raising of virtually another AASC from scratch, then expanding it sixfold inside 18 months, including new types of units and motorised units, was both a quantum jump and a wasteful negation of the previous standards achieved by the Corps. Progressive strength increases in the AIF were also multiplied by throughput of members, both combining to bear heavily on training levels and experience. War is a demanding and unforgiving tutor and, as with the remainder of the AIF, AASC units and staffs had, of necessity, to learn and adapt quickly, establishing with British Army assistance their system of school and on-the-job training. For all the stories of problems with overbearing British commanders and staff who had difficulty in appreciating Australian ethos and methods, and sometimes silly ways they tried to impose inappropriate standards (only gentlemen drive from the box, soldiers must ride postilion 8), the AASC owes a great debt for the unstinted and selfless assistance provided by the British ASC, staffs, depots and schools. It also owes more to the capacity of its own members to adapt and apply themselves to the missions impossible presented to them.

1st Division was dispatched to Egypt partially trained at the end of October 1914 in order to meet the time-frame agreed with the British Government. While the divisional train, supply, bakery and butchery requirement was well enough understood from its equivalents operating within the AMF context, the motorised supply column and ammunition parks were a novel proposition. Selective recruiting and purchase of the best range of vehicles available plus some ingenuity in fitting workshop vehicles saw them leave in some order, only for the majority to be sent on to England as they were not required with the divisional group in Egypt 9. Nor, as it turned out, was most of the horsed transport as the failure to break out at Gallipoli meant that the transport of both 1st Division and New Zealand and Australian Division was left at Alexandria (the NZ and A Div Train was mainly NZASC, with 5 then 7 Coys filling the extra position). This reduced requirement for AASC made the formation of the 2nd Division for service on Gallipoli from newly arrived brigades a relatively painless task, as divisional supply and transport units were raised and dispatched progressively from Australia and there were sufficient resources in Egypt to make up the small component required at Gallipoli. These extra companies, together with the elements improvised in Egypt and sent to the Peninsula, came in great use in the subsequent major expansion.

This real test of depth came with the decision in February 1916 to clone 4th and 5th Divisions from 1st and 2nd Divisions and, with 3rd Division raised in Australia, provide a major force for employment in France. In addition the Light Horse was grouped to form the dominant Australian component of Anzac Mounted Division for employment in the defence of Egypt; this was supplemented a year later by providing half of the additional Imperial Mounted Division, which in turn became the Australian Mounted Division in August 1917. The expansion, plus the requirement for lines of communication troops to hook into the British infrastructure in France, necessitated raising in Egypt an extra eight horse transport companies for the divisional trains, 13 depot units of supply, and two each of field bakeries and butcheries. These were formed from two horse transport companies (7,18) surplus from the existing two divisional trains (1, 2, 3, 4; 15, 16, 17, 20), the transport elements of four light horse brigade trains (5, 6, 12, 14) and lines of communication units (11, 13, 19, 21); by reallotting 1st Division's un-needed Reserve Park (10 Coy); from the ammunition and supply sections of 8 and 9 Coys which had remained in the Middle East; and from reinforcements. There was also a manpower multiplier in changing from four-horse wagon teams to the standard British two horse arrangement 10. Missing of course from this lineup in the Middle East were motorised corps troops units – the divisional ammunition parks and supply columns.

The motorised corps support units of 1st Division (8, 9 Coys) which had gone on to England had been re-equipped and deployed in France, where they were reorganised into ammunition sub-parks and a supply column. On arrival of the Australian divisions from March 1916 they were reallotted as corps troops ammunition sub-parks for 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions and supply column for 1st Division. The supply columns for 2nd and 4th Divisions and both sub-park and column for 5th Division were provided by British units, while the Corps Troops Supply Column for I Anzac Corps was cloned from existing Australian units 11. 3rd Division raised its own full complement at the ASC Depot Bulford in November 1916 immediately prior to deploying to France. A decision to centralise control of motorised units at corps level saw the January 1917 formation of HQ I (K) and II (Y) Anzac Corps MT, each under a Senior MT Officer, and commanding the corps supply columns and ammunition parks shown in Table 2, which were as yet still a mixture of Australian and British units. The mid-1917 arrival of 1, 2 and 3 Auxiliary MT Coys from Australia allowed plans for their conversion to 2 Div Sup Col, 5 Div Sup Col and 5 Div Amm Sub-Park at the Rouen ASC Base MT Depot, plus Australianisation of HQ K Corps Sup Col. With this in hand it was then proposed to convert the remaining corps motorised unit by using Australian reinforcements and reallocations as they became available: 4 Div Sup CoI was finally taken over in September. However a mixture of units persisted as the two Anzac corps themselves were composed of mixed nationality as divisions moved in and out of them for particular operations, and it was not until the concentration of the Australian divisions into 1 Aust Corps in December I917, with subsequent refinement by the formation of 1 Aust Corps MT on 9 March 1918, that a fully Australian supplies and transport support organisation existed forward of railhead, with its own AASC Railhead Supply Detachment (11 Coy) and Sea Transport Service terminal component 12.

By mid 1916 the AIF had reached its peak. Ideas of forming a 6th Division foundered in the Somme slaughter and failure of the first conscription referendum. Combined with a slowing of volunteers, this nearly resulted in the disbandment of 3rd Division, which until late in the year became in effect a reinforcement depot; also on the brink were the light horse brigades arriving in the Middle East to form the Australian Mounted Division, being eyed as a source of badly needed infantry reinforcements. Another attempt at raising 6th Division in early 1917 was finally abandoned in September as the continuing drain of casualties, added to loss of the second conscription referendum, ended any prospect of a new wave of soldiers available to make and maintain an expanded force. In consequence 30 and 31 Coys raised for the proposed 6 Div Train were disbanded, but Anzac and Aust Mtd Div Trains (32, 33, 34; 35, 36, 37, 38 Coys) were raised for operations in Palestine in August. So the equilibrium level was struck, with difficulty, at seven divisions 13, and for the AASC, the order of battle shown in Table 2. These units filled their roles effectively and often with distinction, as was noted by both their own commanders and those of British formations. Of the nearly 10,000 AASC members of the AIF, mortality was 341, low totals indeed when compared with the carnage suffered by the infantry, but still significant when their roles and locations are considered. It is a remarkable testimony to their performance and willingness under fire that a supporting arm of the service should have garnered the types and numbers of gallantry awards listed in Appendix 2.

Postwar Reconstruction

Return and demobilisation of Australian troops from abroad was a slow process, and planned to be so to facilitate reabsorption of the soldiers into the workforce, with the last contingent not home until January 1920. Composition of the postwar Army was not a high priority until this had been completed, but when a Senior Officers Conference comprising ex-AIF members was convened later that year to plan its future shape, it is not surprising that the shape recommended should have matched that of the AIF which had been successfully tested in battle, and for which the warlike stores had been brought back to Australia. Nor is it surprising that the system of providing the soldiers for the Army should have continued to be the universal training system instituted in 1912, which had by 1920 both matured and, to some degree at least, maintained a home training army. That system had also benefited the large number of volunteers to the AIF from its ranks, and saved the AIF having to look over its shoulder to home defence. Still less surprising was acceptance of the proposals by a government dominated by wartime Prime Minister Billy Hughes and Defence Minister Pearce, together with a new contingent of ex-AIF parliamentarians. The 1920-21 budget provided for five infantry and two cavalry divisions totalling 100,000 Militia and a Permanent cadre of 3,150 14.

The big loser in this apparent retention of a strong, balanced fighting force was the AASC. Although a 1919 AIF HQ Conference in London produced a report proclaiming the essentiality of motor transport for a modern army, and proposing a Director General of Transportation controlling rail, motor and horse transport, the motor transport was not brought back from France as were the weapons, so the motorised column of nearly 500 vehicles disappeared without resurfacing in fact or even paper in a regression to a horsed army. The Senior Officers Conference in Australia, while acknowledging that 10,000 men were required in motor transport as an essential support component in and for the seven divisions they proposed, sentenced it to be deferred in toto. And to rub salt into the wound, a 1922 decision 'that transport facilities should be used in common' allotted sea transport to Navy, horse transport to Army, and to Air Force, not air transport but motor transport, which existed in some numbers at Point Cook 15: the fledgling was showing early its propensity for grasping for empire at the expense of the other Services, and AASC reverted into a slough from which it crawled painfully and belatedly into the mechanised battlefields of World War 2. Purchase of five vehicles in 1925 was such a novelty that it called for the establishment of a mechanical transport training wing in the ASC and Q Administration School subsequently set up in Melbourne 16.

Not that this loss of capability was unique for long: the Imperial Defence Conference of I921 and the Washington Conference later in that year echoed the sentiment of a war weary world for disarmament. In consequence, although the plan for the AMF structure remained, manning was reduced to 25 percent in the Militia, and the Permanent component halved. AASC's share was the training component of two cavalry divisional trains, four infantry divisional trains and three composite brigade companies for the fifth infantry division: 1st Cavalry and 1st and 2nd Division Trains in 2 MD; 2nd Cavalry and 3rd and 4th Division Trains in 3 MD; Head-quarters of 5th Division Train and the No 4 Companies from each of 1st Cavalry and 1st Division Trains were located in 1 MD, and the No 4 Companies from 2nd Cavalry and 4th Division Trains in 4 MD. As well 11, 13 and 12 Bde S&T Coys, representing the components of 5th Division Train, were located in 1, 5 and 6 MDs respectively. Elimination of the specialised corps transport and supply units and retention of horse transport took supply and transport training and support back to Hutton-army levels and techniques, and at the reduced training manning level. Gone were not only the motor transport and the opportunity to practise the tactical skills required for support of major field formations, but also the order of battle structure for logistics units beyond that necessary to support the training camps now reduced back to six days a year 17.

Former Desert Mounted Corps Commander Lt Gen Sir Harry Chauvel as Inspector General of the Army submitted annual reports to Parliament from 1921 recording a decline in capability, as whatever emphasis there was on defence was channelled into maritime and air defences. Not only was the provision of one 30 cwt truck for each mainland military district derisory, the decline in working horse stocks as the civil community mechanised cast doubt in his mind on national capacity to supply sufficient to mobilise the Militia. Even the Army remounts were wasting away, a quarter being over 16 years old with no provision of funds to replace them, and the permanent Remount Sections insufficient to train and maintain them 18. In this losing equation, even the horse-soldier tradition could not avoid some degree of compulsion towards mechanisation. But recognition merely highlighted missed opportunities, coming too late to rectify them in a climate of reducing defence funding and competition between the services, in which the proponents of air and naval power made the extravagant claims of omnipotence which are still so familiar in present generations. In such an adversarial climate, the proponents of big equipment solutions, which make for impressive ministerial announcements and instant solutions to defence problems, understood all too well the cash translation of Army manpower and its very modest equipment needs into warships and aircraft, and sought to denigrate the need for ground forces, just as they do to this day regardless of the salutary lessons of the past.

Token mechanisation proceeded. As a face-saver, Inspector General Chauvel proclaimed after procurement of the five light trucks and eight Hathi gun tractors in 1925 'that mechanisation has been effected', and that a small mechanically trained nucleus was necessary for rapid mechanisation of the divisional AASCs on mobilisation – the nucleus was to be very small indeed as three men were trained in mechanical transport courses in that year of 1927. With so few human and materiel resources, the Permanent Army transport staff of fewer than twenty became in effect a 'mechanical remount section', holding and maintaining the few gun tractors and cargo lorries for use by Militia units and courses at camps and bivouacs in between routine base cartage tasks 19. As there was also a pool of staff cars to operate and maintain, the following year the paucity of available effort could no longer be ignored. Permanent Artillery and Engineers soldiers were detached to the Supply and Transport Section of AASC in the main military districts to prop up the few drivers struggling to undertake transport tasks not only within the Army but also for other Commonwealth departments in order to save freight and cartage costs, as well as maintaining the vehicles and assisting Militia unit training in camp. This arrangement solved nothing, as the lightly manned donor units had their own activities crippled by the diversion of members from training to administrative tasks 20. It was a very slim base from which to face even tougher times ahead.

The Depressed Years

Installation of a Labor government committed to abolish compulsory training coincided with the first steps into the Great Depression in October 1929. The Universal Training Act was suspended and all training camps for the year cancelled. Retention of the current Permanent force and a substitute volunteer Militia of 35,000 supplemented by 7,000 senior cadets undertaking eight days each of camp and home training was planned. Inspector General Chauvel's term in office ended, his final 1930 report recording 24,000 Militia and 5,300 Cadets, a remarkable achievement of rebuilding a volunteer force in such a time, and also remarkably similar to recent experience with a volunteer army. The deepening depression added a financial bite to the strictures of ideology, resulting in the Army vote being reduced by one third. By 1932 strength and funding for the Army in Australia were at the lowest level since Federation, at a time when Japan and Germany were making their transitions to overt militarism, and although a change of government in 1931 brought a gradual turnaround in more allocations to defence, the political view of primacy of maritime and air power as the determinants of future war dominated. This misconception ensured that little of a modest seepage of extra money found its way to the Army 21.

Within this dismal scene the AASC stagnated and struggled with the rest. Equipped to pre-1915 standards, it was worse off than the combat units which at-least had equipment up to the best of 1918 levels, although all was by now showing age and shortages 22. The organisational level and strength of the 15 Militia companies in no way matched the notional order of battle of seven divisions, but then those formations were mere quarter-strength shells in which dedicated militiamen and their Permanent cadre staff determined to keep the spirit of the Army alive. At least there was a permanent AASC component permitted by the Defence Act which prohibited standing army units other than artillery and some technical corps. Not that the supply, transport and remount sections in each district capital were a substantial force component in themselves, but they provided an element of continuity and benchmark of standards that, together with the instructional corps members and district staff, retained memory and knowledge which could flow through to the Militia. Amidst this apparent gloom and doom there was, however, a bright light – the enthusiasm of the soldiers, Permanent and Militia. It is a noticeable and remarkable fact that the degree of despondency increases dramatically the closer one gets to the seat of power. Practical unit soldiers and district staff are, if they are any good, problem solvers and, in the real world of unit training and support of the base and field units, are too immersed in getting things done to brood over macro problems. The microcosm of a working unit, if properly commanded, administered and employed is one of high spirit even in the most difficult circumstances; this spirit carried the AASC through the early difficult years, then the later depressed years.

For the Militia the revised field force establishments of the RASC were adopted from 1 July 1928: the divisional train was replaced by a HQ ASC (not bothering to insert the extra A to Australianise it), four companies renumbered A to D, a horse transport company, and four depot supply sub-sections (shades of the depot units of supply) for each infantry division and two for each cavalry division. This field organisation was then changed by absorbing the four companies and supply sub-sections into a divisional supply company without any transport component, and separate transport companies, giving a HQ ASC, Supply Company and Horse Transport company per division. The reason for this diversion from the well recognised integrated supplies and transport concept was 'to facilitate the training of MT personnel and provide the nucleus for the formation of baggage and ammunition units', itself a reversion from the successful World War 1 development of composite units. NSW and Victoria retained the six divisional AASCs, while mixed brigade supply and transport units sufficed the other states - 11 Bde Sup Coy and 11 Bde HT Coy in 1 MD, with HQ ASC 5 Div retained as a temporary consolation prize; HQ ASC, two supply sections and two HT sections for 4 MD; and 18 and 12 Bde S&T Coys each comprising a supply section and horse transport section for 5 and 6 MDs.

A further round of changes in 1934 expressed good intentions in the mechanical transport field by renaming HT companies as MT companies, though there was not the equipment to give reality to this. As a minor rationalisation 4 MD's supply and transport sections were upgraded to Sup Coy and MT Coy in line with the strength of the forces in the District. To put this progressive restructuring and expedient grouping into perspective, the RASC had finished motorising its divisional trains in 1928 and was now nearly completed on the same for lines of communication units. But RASC organisations were being adopted for the AASC without the motor transport to make them work, then altered to peacetime organisations to compensate for and camouflage the deficiency 23.

Towards a New Conflict

Realisation and realism began to take root after 1934 with adoption of a three year re-equipment plan for the Army. Not that any dramatic infusion was effected, but the tide had turned. Included in the plan was the follow up of the 1933 decision to motorise the AASC 24, a course that was becoming increasingly inescapable as use of horses continued to decline in the civil community and the Army became increasingly isolated in its approach to transport at home, much less in the international context. However no floodgates opened. The practical effect was to motorise the Permanent AASC which, with 169 drivers by early 1939, was tokenism in an Army of seven divisions, each of which with its corps troops slice required 3,000 vehicles. Although Treasurer Casey declaimed in 1938 that 'any money Defence wants it can get’ 25, equipment did not flow in quantity. While for major weapons this could be blamed on long back-orders from British factories struggling to re-equip the British Army, supply of motor vehicles trickled at a rate which saw the AASC grow from 13 cargo vehicles in 1933 to 100 in 1939. AASC motor transport drivers were then outnumbered by their remount colleagues by over two to one.

Although the equipment was not there, at least the structure for modern warfare was beginning to appear as organisations followed the British model. The British ASC transition from theory to practice of full field mechanisation was essentially completed by 1938, and with this came effective motor transport establishments together with provision for supply of liquid fuel in quantity. The advance was not, however, without its regressions. RASC establishments reverted from the well-learned composite or pooled system of late World War 1 to the earlier commodity system which had been progressively dismissed as inflexible and uneconomical. The result was an headquarters, a supply column, and petrol, baggage and ammunition companies, which was notionally adopted for the AASC, but its implementation was not carried through in practical terms to mechanical transport simply because the cargo vehicles available up to the outbreak of war amounted to three per division; the baggage companies never eventuated, transport sensibly being allotted to all arms units for this purpose, and the petrol companies were symbolised by a section in each supply company. There was, however, a clear appreciation of the dangers of neglect. Chief of the General Staff Lavarack wrote a thoughtful and illuminating comment to the Adjutant and Quartermaster Generals, some excerpts of which are reproduced here, as their significance on the periodic splits which occur in the distribution of the sinews of war in peace is catholic 26:

An examination of the peace organisation of our ASC indicates a necessity for revision to bring it into conformity with our war organisation. Our cavalry divisional, divisional, and mixed brigade ASC is at present organised as – Headquarters, Supply company or section, MT company or section, S&T company in 5 and 6 MDs.

The supply company or section consists solely of administrative and supply personnel and has no vehicles of its own with which it has to carry out its supply functions. For this purpose it has to obtain vehicles from the MT company. This does not appear to be a satisfactory arrangement from the functional aspect of the supply column in peace, and tends to give a false impression of its operation in war. Further, the OC Supply company has no practice in the control and maintenance of his own vehicles.

It is understood that the reasons for separating the transport personnel were to facilitate the training of MT personnel … I see no reason why the training of MT personnel should present any great difficulty if they are included in the supply unit where they properly belong.

Those statements should not be misinterpreted as a proposal to set up a separate supply organisation with its own distribution organisation; the supply column was a distribution organisation, which had been neutered by losing its transport. Transport specialists had lost sight of the distribution function and successfully sought to set up a separate transport organisation. Commonsense from an operationally experienced soldier brought the system back to rationality in time for the beginning of World War 2.

This intermediate restructuring was completed by 1938 in accordance with the establishments outlined in Table 12. It was not a clean restructuring as the sizes and variety of the specialist AASC units required, together with the sizes of the formations in each district, were way out of synchronisation. This was to a large degree a product of the pernicious habit of allotting all divisional and supporting headquarters to NSW and Victoria; it applied to the fighting units on a larger scale, as tradition and available skills had continued to influence the distribution of mixed mounted and dismounted units and formations in different States. In consequence the allocation of AASC units at the outbreak of World War 2 was both incomplete and scattered as demonstrated in Table 3. That problem was by no means new, indeed the AIF had been raised that way in 1914 although the potential benefit of such regional affiliations had not been exploited properly in the reinforcement system. Nor was this to change in the decades ahead, which always made it difficult to achieve a balance for the supporting arms in the Citizen Forces: a less than forceful command system, at least in voluntary recruitment periods, allowed available manpower ceilings to be absorbed into the preferences of traditional regional regiments and battalions rather than the real needs of a balanced order of battle which included longer lead-time skills and training.

The process of mechanisation was much drawn out. It had begun perforce during World War 1 with gifts, hiring and acquisition of some working motor vehicles which were promptly diverted to staff cars in the military districts, from which the staffs and Military Board could not later be weaned. Some lorries and ambulances were also similarly obtained, resulting in the formation of MT Depots in each capital, largely manned by civilian drivers, but withdrawal of financial cover for their wages in 1923 ended these depots and reduced the carryover to a few staff cars. Procurement of five Thornycroft 30 cwt trucks in 1925 added to this minor empire, and the addition of gun tractors and a few other vehicles enabled the establishment of MT Sections at Victoria Barracks in Sydney and Melbourne in 1928. This move to mechanisation had some interesting sidelines. AASC, after the mirage of Air Force being responsible for motor transport had faded, on the strength of its five vehicles in 1925 became doyen of matters mechanical, holding all vehicles, and training officers of all arms and drivers for RAA and RAE. The 1933 mechanisation decision resulted in the establishment of a separate ASC Training School the following year with staff trained with the RASC; Senior Instructors of its Mechanical Transport Wing doubled as staff officers of transport in the Directorate of Supply and Transport, Movement and Quartering; and officers commanding mechanical transport units in the District Bases were also variously staff officers transport and instructors of MT training 27.

This dominance of mechanical operations and maintenance led to a unique diversion of the embryonic tank unit, first formed by light horse members as an experimental unit with a Vickers medium tank at Randwick in 1927, then raised in 1930 as 1st Tank Section at Randwick from permanent RAA and RAE members. In 1932 it was belatedly realised that the Defence Act did not allow for a Permanent Tank corps, and it was also recognised that the permanent diversion of artillery and engineer members robbed the parent units of manpower and the members of career progression from corps which had no further interest in them: 'The unit to which mechanical training of the Tank Section seems most analogous and which is next in order of precedence of corps is the Mechanical Transport section of the AASC (permanent)'. The Tank Cadre became Permanent AASC and part of 1 MT Coy at Sydney and Iater its successor 2nd District MT Depot. OC of 1 MT coy, Capt A.J. Stewart became OC of the Tank Cadre (Permanent) and Instructor of the Militia 1 Tank section; successor at 1 MT Coy Lt D.G. McKenzie was also Tank Instructor; a similar arrangement was established at 3 MD MT Depot in Melbourne in 1938. There were of course no illusions here of AASC becoming the new power on the battlefield, but this sensible use of a specialist environment assisted the survival and training of the beginnings of the Australian Armoured Corps in an otherwise unsympathetic world of horse soldiers. Yet the historian of the Armoured Corps, while erroneously attributing an initial infusion of AASC drivers into the Corps when in fact they were engineers, manages to avoid this era quite completely. In addition his account of development of a prototype armoured car by Maj E.A. Wilton describes him as 'technical staff officer in Q Branch'; he was not just in Q Branch but Staff Officer (Technical and Equipment) in the Directorate of Supply and Transport, Movement and Quartering, and from 1930 until his death cut short the project in 1932, Chief Instructor of the ASC and Q Administrative School 28. These evasions are less than generous to a Corps which was a friend in time of real need.

Each district had a complement of district base Permanent and Militia troops for the provision of local support. Motor transport was catered for by a mechanical transport company or section, with mixed types of vehicles tailored to the local requirement. District remount sections were still responsible for providing horses for the Army as a whole, and the token mechanisation made this a sizeable task which resulted in the raising of a Militia remount troop for each district. In fact a larger problem was avoided with the Militia cavalry by paying soldiers to bring their own horses to training and providing rail transport for concentration in camps; horsemen were paid four shillings and sixpence a day, and five shillings for their horse. In addition to the transport, 2nd and 3rd District Bases had a Permanent supply section from 1935 and each State capital raised a Militia supply personnel company in 1938, into which the Permanent supply sections were absorbed; these supply personnel units were not the human equivalent of the remount units as the empty-headed inventor of the title would seem to have indicated, but units which supplied to personnel. Their sections could ration training courses and camps in peace and set up base and operational depots in war. District base units were under the control of the Supplies and Transport Staff on the military district headquarters - these varied in title, but essentially were comprised of an ADST or DADST, plus supply, MT and technical staff officers. A late 1939 addition in 2nd and 3rd Military Districts raised Militia HQ AASC as intermediate headquarters to command the base units planned for Mobilisation 29.

Table 4: AASC Strengths 1914-1939

In summary, the organisation, equipment and training of the AASC was on a par with that of the rest of the Army. Gavin Long comments that the Militia in general was better than that of most foreign armies 30, but of course Australia was set on a path of mixing and mixing it with professional standing and long-service conscript armies. New generations of equipment in an increasingly technology-influenced battlefield were not the stuff from which instant armies are made. The AASC as a whole faced a near standing start in the operation and maintenance of motor transport, and in acquiring that equipment was reliant on hire and impressment of civilian vehicles at the same time that increased pressure on industry required more not less transport. Also to come from a zero base were liquid fuel supply to match the conversion from forage to petroleum fuels, and raising the supply and transport units required behind the division, which had simply been left off the order of battle as had happened prior to World War 1. But perhaps the greatest hurdle lay further ahead in the Pacific Theatre, where the Australian Army was not only bereft of the hitherto-usual comfortable arrangement of relying on the British Army base and forward supply and transportation system, but also had to provide a large measure of this support to United States forces as weII as its own. The locusts had eaten twenty years; retrieval of them was a challenge which the successors to the First AIF's AASC would have to meet.

Footnotes

1. Scott E. The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 vol XI p11; Bean vol I, p33-4, 36-7, 60.

2. CPP 1917-19 vol IV Proposals of the Government for Home Defence of Australia, p3.

3. MO 1/1917, 150/1919, 103/1920 and amendments.

4. See Note 18 to Chapter 2.

5. Report upon the Department of Defence Part 1 1914-1917, p296; AWM 26 369/4 of 26 July 1918; Bean vol I, p29; vol III, p50, 163, 169, 178-80; Scott, p232-4.

6. Fairclough H. Equal to the Task, pxi, 28.

8. See Keogh E.G. Suez to Aleppo p46; yet Bean vol III, p56 stamps this as 'sound military rules'; for another view Gullett H.S. The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 vol VII, p106, and the clincher in AWM 25 327/5 Part [13] Comments by GOC.

10. AWM 25 721/29 A & NZ Force 136/46 of 23 February 1916; 136/75 of 2 March 1916; Bean vol III, p42-3, 55, 805-6.

11. AA MP367/1 631/1/132 Appx 7; AWM 25 72/81.

12. AWM 25 721/28 of 1 April 16; 327/10 Pt [3] 20/ASC/1018 (QMG 3) of 19 October 1916; AWM 26 159/1 of 17 Feb 1917; 227/16 of 7 and 17 June 1917; 227/19 of 6 September 1917; 292/8 of 9 March 1918; AWM 224 MSS 250, 241; AWM 25 227/16, 227/18.

13. Bean vol III, p866; vol IV, p316, 344; AWM 224 MSS 212.

14. ANL MSS 1827 1.1 Report on the Military Defence of Australia by a Conference of Senior Officers 1920 vol II, p21; CPD vol 97, p11736, 12848; vol 93, p4392.

15. AA MP 367/1 631/1/132 of 11 June 1919; ANL MS 1827 1.1 Senior Officers Report, p22; CPP 1922-3 vol II Department of Defence Estimates, p5.

16. Military Board Instruction Q96/1926; Australian Army Order 501/1926.

17. CPP l922 vol 2 Chauvel Report, p7, 10, 11; 1926-28 vol II Chauvel Report to 31 May 1926, p6.

18. CPP 1920-1 vol 4 Chauvel Report, para 109; 1923-4 vol 4 Chauvel Report, p23; 1926-8 vol II Chauvel Report, p21.

19. CPP 1926-8 vol II Chauvel Report to 31 May 1927, p16, 18, 20-1.

20. CPP 1926-28 vol II Chauvel Report to 31 May 1928, p14, 18, 23 and Appendix A.

23. CPP 1926-8 vol II Chauvel Report to 31 May 1928, p14; Army List 1929; Commonwealth Year Book 1929, 1934; AA MP729/6 37/401/79 of 21 August 1937.

24. AA B1535 763/A63 Military Board Agenda 65/33.

26. AA MP729/6 37/4O1/79 of 10 February 1938; 37/401/79 of 21 August 1937 and Appendix A CGS Minute on Peace Organisation AASC.

27. AA MP367/1 631/1/32 of 28 August 1924; CPP 1926-8 vol II Chauvel Reports: to 31 May 1927, p18; to 31 May 1928 Appendix B; Army List 1926-30, 1935-37.

28. AA B1535 736/2/59 Military Board Agenda 2/32; Hopkins R.N.L. 'Origins of the Australian Armoured Corps' Stand To March-April 1954, p10; Australian Armour p16, 20, 22; Army List 1926, 1930, 1935-39.

29. Army List 1934-39; AA MP729/6 31/401/79 of 21 August 1937 Appendix A.