Imperial-Australian Relations in the

Formation of the Royal Australian Navy

There is nothing new in the phenomenon of the current debate on defence preparedness being conducted in a partial vacuum of vague, unspecified or unquantifiable threats, leavened by spasmodic international crises. The environment which saw the genesis of Australian federal defence policy, and consequently of Australian naval development, was equally as undefined and erratic. Yet there was a unique flavour in this early period, with Australia still uncertain and inhibited: ‘a navy within a navy – a logical outcome of a nation within a nation, which is the recognised position of each of the self governing dominions within the Empire' ’1. The major step towards reduction of this ambiguous position was consolidated at the Imperial Defence Conference of 1909, although this development cannot be considered in isolation. An examination of the establishment of an independent Australian naval force needs to include both the extensive debate, manoeuvrings and tradeoffs of previous years, and the subsequent Admiralty rearguard action which persisted until the actuality of the Australian fleet, followed by the practical arrangements of the Great War, finally terminated the debate.

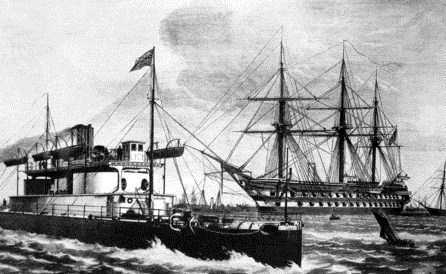

Argument on the status of local naval forces started relatively early in colonial history. Legal opinion in 1860 found that, in international waters, official status could be given only by commissioning into the Royal Navy – the opening shot in the ‘one navy’ doctrine. In consequence Australian colonial governments were left in no doubt that there was but one navy: their own maritime units were relegated to the three-mile limit. Subsequently the Colonial Naval Defence Act of 1865 allowed Colonial warships to exist at imperial pleasure, and provided the machinery for absorption into the Royal Navy: this plus the legal position effectively limited them to harbour defence 2. Herein lay the seeds of future disagreement as whilst some colonial governments were anxious to have ocean-going warships to project their influence across their perceived security zone in the Pacific, the Home government wished for just the reverse 3.

This fear of irresponsible colonial and federal governments committing Britain to unsolicited and unwanted adventurism, particularly against the territories of European powers, haunted imperial ministers up to the Great War, and was an equal force to that of the Admiralty fetish for absolute control, in the opposition to the emergence of an autonomous Australian fleet. Australia’s security was Empire security and so the province of the Royal Navy, which established an Australian Station with a permanent squadron in 1859. That arrangement, supplemented by colonial defensive batteries and inshore warships, was fairly satisfactory until German and French penetration into the Pacific, together with the 1885 confrontation with Russia in Afghanistan, stimulated demands for greater and better guaranteed protection. The most coherent enunciation of colonial demands, including those of New Zealand (and tacitly of Fiji) was formulated at the inter-colonial convention in 1883, but it was not until the 1887 Colonial Conference in London that these demands gained some response, with an Australian Auxiliary Squadron to be raised (in addition to the imperial squadron on station) which could not be employed outside the Australia Station without colonial government authorisation; the colonies met the expense. This agreement was re-endorsed at the 1897 Conference on Admiralty assurances that their requirement of uninhibited control did not include the withdrawal of Auxiliary ships to other theatres 6.

Federation rested partially on defence considerations 7. Consequently mid-1901 saw Prime Minister Barton canvassing the opinion of the Flag Officer Commanding the Australian Station on a national naval force. The response predictably proposed the retention of an updated Royal Navy squadron, with costs shared with Australia and New Zealand, and provision for some dominion manning and reserve capacity. Consolidation of the colonial naval forces into an indigenous navy was deemed impractical 8. This line of advice was consistent with the guidance of the Colonial Defence Committee, which postulated no threat to Australia or its sea lanes as long as the Admiralty maintained general supremacy at sea 9, advice strongly supported by the Commandant of the Australian Military Forces, Major General Sir Edward Hutton, who was pushing his land force proposals 10. However, the then Naval Commandant in Queensland, Captain W.R. Creswell, differed strongly, calling for the progressive build up of an Australian fleet, so beginning his long and unrelenting personal crusade which culminated in the arrival on station of the Australian fleet in 1913. Yet Creswell’s initial demand was made without the identification of any particular threat, simply that a situation which concentrated the British fleet in Europe left Australia at the mercy of the ‘merest privateer’ 11 The lines of debate were falling clearly about the credibility of Britain’s will and capacity to honour its obligations for imperial defence in the East 12.

Although this debate was gaining momentum, a persuasive Admiralty hard line ‘one sea’ approach at the 1902 Colonial Conference succeeded in convincing a relatively naive Prime Minister Barton to remain with an imperial fleet encompassing the Australia, China and East Indies Stations, with provision for training of Australian and New Zealand reservists as well as continuance of partial funding by those countries. He rejected an Australian navy on the basis of unity of naval forces and cost of an adequate independent force, against home-based counter-argument that this agreement was an abandonment of the Australian Auxiliary Squadron and its expected development into a national force – a concept which had been conceded by the Admiralty in 1887 and one encouraged by Admiral Tryon, the then station commander 13. Yet these arguments were largely academic without the focus of a perceived threat other than faceless ‘raiding cruisers’. By 1905, Creswell was still pressing his argument on the platform of contributing to imperial sea power combined with defence against an unspecified and unquantified local sea threat 14.

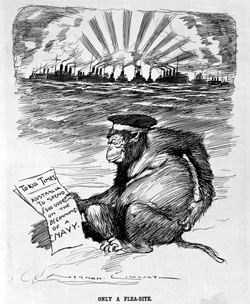

Prime Minister Deakin was well aware of widespread lack of enthusiasm for the naval subsidy or ‘tribute’ scheme, having earlier reported public distrust of Britain’s reliability, and the well-accepted expectation of an Australian navy, under a pseudonym in the British Morning Post of 6 January 1903 15. However by 1905 there were some hard external threats to conjure on: Britain’s indifference to Australian concern on the New Hebrides issue, and the recognition of Japanese power after its defeat of Russia 16. Deakin consequently raised the prospect of a revision of the 1903 Naval Agreement, a proposal which met a cold response from the Admiralty. Similarly, Creswell’s proposal for a local naval defence force drew a negative response from the Committee for Imperial Defence 17.

In these successive rejections, Britain not only showed insensitivity to Australia’s concerns and aspirations but also overplayed the hand of paternalism to the extent where Deakin’s government partially authorised Creswell’s proposal, in the form of a 'three year trial of a basic local naval defence force, to be extended and expanded if this should prove workable’ 18. Subsequently in a brief to the Prime Minister prior to his departure for the Imperial Conference of 1907, the Australian Station Commander Admiral Faulkes made counter suggestions to these decisions 19, which drew from Creswell the criticism that their thrust was to alienate Australian control of any naval forces whatsoever. In rendering his own advice, Creswell for the first time came forward with a clear and specific strategic assessment which identified European and Japanese threats to Australia as the basis for a progressive move to naval self sufficiency 20.

This proposition was not pressed at the Imperial Conference by Deakin, who was satisfied by a newly-flexible Admiralty approach supporting the mooted local defence force ‘solely under Commonwealth Control’ 21, a limited gain but nevertheless one which encouraged Creswell to advise the government in terms which embodied termination of the ‘tribute’ and the raising of an Australian flotilla 22. Still the Admiralty prevaricated and the government’s uncertainty on public support and availability of funds resulted in procrastination. Early in 1909 Creswell was constrained to advise that the residual colonial-era ships were now ineffective, the imperial squadron was under strength and liable to redeployment, and measures for the raising of the Australian squadron agreed at the Imperial Conference two years earlier were in limbo. In consequence, the incoming Fisher Labor government ordered three destroyers and advised the Colonial Secretary of its intention to allow the 1903 Agreement to run its ten year course, whilst proceeding to organise a local naval force 23.

This decision was made parallel to the ‘dreadnought crisis’ – Britain’s reaction to a German naval expansion which threatened her naval superiority. Canada had offered assistance and New Zealand, in line with its customary approach of subsidising imperial naval protection, offered to pay for a battleship. The Fisher government offered unspecified support, an evasion which led New South Wales and Victoria in consortium to guarantee that New Zealand’s offer would be matched. As a counter to this, Fisher requested a Dominion Conference to formulate naval proposals, which arrangement was already being pursued by the United Kingdom. However, before this conference the Fisher government fell, and the incoming Deakin administration found it expedient to offer to contribute an Australian battleship or its equivalent to the imperial forces 24.

Public sentiment and the consequent opportunism of the two senior state governments had forced Deakin to make this gesture of imperial solidarity, as much as he may have wished to send his delegation to London without any prior specific commitment. His own position as a proponent of an independent Australian capacity is attested by both his parliamentary statements 25 and his self-confessed astute manoeuvring over the ‘Great White Fleet’ visit of the United States Navy in 1908. This latter exercise, following on the failure of the Hague arms limitation conference and local anti-Japanese reactions, and added to subsequent further German naval expansion plans 26, provided the catalyst which allowed him to get his stalled 1907 Conference initiative moving 27. But even though this strengthening of public support may have become more enthusiastic than he would have preferred, resulting in the New South Wales-Victoria initiative in outbidding his federal offer, he was astute enough to retrieve the situation by offering an Australian dreadnought. As a consequence of these manoeuverings, the delegation to the Imperial Defence Conference on July 1909 could be briefed to insist on an Australian naval force in the confident expectation that public support and the attendant budgetary support could be assured.

This trump card was made all the more effective by Britain’s awkward situation in Europe. Either or both as a consequence of its straightened circumstances, and perhaps of facing the inevitable but hoping to manipulate the result, the Admiralty submission to the Conference acknowledged the Dominions’ entitlement to make arrangements which best suited their own needs and preferences, and accepted the definite prospect of the establishment of Dominion navies. Where such a choice was made, the proposal recommended that a navy be constituted as a balanced fleet unit so as to be capable of both independent defence and integration into a fleet 28. The full implications of this duality were to become apparent in later years as Britain’s strategic centre of gravity shifted more clearly to the North Sea. However, the Dominions found these proposals very persuasive and agreed that the Pacific should have a fleet with three units – one each to the China, East Indies and Australia Stations. The Australian unit was to be provided by Australia, while the New Zealand sponsored battle cruiser would head the China fleet, a decision it was later to regret. Canada, sheltered by America’s Monroe Doctrine, was satisfied with two minor units, one on each of its seaboards 29.

Of the three Dominions, Australia alone came out of the Conference with the prospect of a clear cut self-contained and significant naval force, at an affordable price and under undisputed command of the Australian Government. In all, it appeared an equitable agreement – Britain offered a subsidy for the fleet unit (later waived by Australia), training, manning and supply support 30. Also included was the free gift of the Sydney base facilities, a move as astute as it was generous, as Australia would bear the future costs while British units could make use of it.

The Australian Government was observably pleased with this deal which so obviously satisfied the country’s and public’s need for both security and a feeling of independence. This solution apparently resolved the incipient widespread doubt on whether Britain could be relied on to guarantee protection in the East in the face of a crisis in home waters. It also gave some relief to those proponents of the ‘yellow peril’ who remained unconvinced that Britain’s treaty with Japan was a positive force for Pacific security or even a neutral one 31: yet even the proposed tripartite Pacific fleet would not in anyway match the Japanese Navy 32. Although the United Kingdom might be quite prepared to chance the value of that treaty in the Pacific compared with the clear and present home danger of the German fleet, Australia could not afford to be so sanguine about fine odds on a threat which embodied the novel but immanent prospect of direct attack by an Asiatic power.

Deakin’s response to this prospect was an attempt to arrange joint USA-European guarantees for the Pacific, although the effort fell on stony ground 33. Nevertheless the Commonwealth Parliament endorsed the new naval proposals with, significantly for the later implementation phase, strong Labor support. The Naval Loan Bill to finance the fleet was not passed without Labor opposition, but this related to the propriety of the proposed British subsidy and a desire not to make a later generation pay for present decisions – matters which the following Fisher government was able to rectify in view of the upcoming termination of the Braddon Clause of the constitution 34. Labor’s essential sympathy with the concept was not at issue.

An early initiative of the incoming Fisher administration was to arrange for Admiral Henderson RN, to advise on the setting up of the Fleet Unit. His report contributed nothing that Creswell had not produced or was not capable of producing, but it lent a stamp of approval to what was to follow, in the form of a 22 year plan 35 – a remarkable presumption on the capacity of governments to see much beyond their immediate term of office. Action on this plan was postponed until after the Imperial Conference later in 1911, but both the Naval Defence Act and authorisation of construction of the warships agreed to at the 1909 Conference had been finalised by the close of 1910 36.

By the opening of the Imperial Conference of 1911, the coming reality of the Australian Fleet Unit was beyond question, however its real ownership was not. Nor was the 1909 Conference Agreement sacrosanct. Britain faced the continuing problems of European naval defence and accompanying budgetary pressure, which made attractive the renewal of the Anglo-Japanese alliance and consequent avoidance of buildup of the promised three-unit Pacific fleet – and this at a time of Dominion insistence on a voice in Imperial foreign relations coupled with US fears of Japanese aggression 37. However, a facade of agreement was worked out, on the basis of British acceptance of the Dominions’ right to consultation 38 (albeit without an effective standing machinery) and the exclusivity of national control of naval forces 39. The Dominion representatives left the Imperial Conference and its associated Defence consultations with a warm glow of having established their national integrity while still retaining close cooperation with the Empire.

Months later the Morocco dispute between Germany and France brought this euphoric attitude back to reality. Australia was not consulted in the British efforts to resolve the problem which included concessions to Germany in the Pacific 40, and Britain turned even more strongly to the European theatre, particularly after the subsequent German decision of 1912 to expand its fleet even further 41. Australia was also to have its first taste of Winston Churchill’s egocentric sense of defence priorities in his plan to leave the Dominions to fend for themselves, again without consultation and in default of the 1909 Conference Agreement. In this climate, Churchill’s inability to recognise any aspirations than his own surfaced in his demand that the Dominions not only provide for their own defence but also make their navies available to the Imperial Fleet 42.

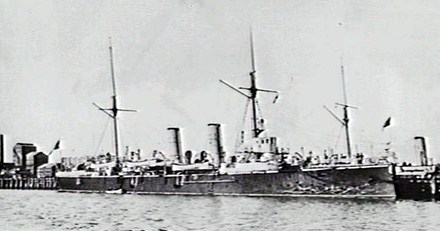

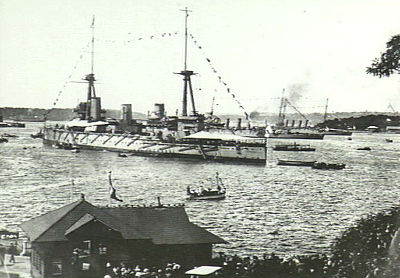

Interestingly, apart from dismay and disgust, the effect of these defalcations on the Australian naval force was one of upgrading and acceleration, based on renewed interest in the Henderson Report. Additional warships and bases were authorised and Australia could patently claim that it had met its part of the bargain struck at the 1909 Imperial Defence Conference, even if others had not 43. On 4 October 1913, the ships of the Royal Australian Navy approved as a consequence of that Conference entered Sydney Harbour; and in accordance with the agreement at that Conference, confirmed at the Imperial Conference of 1911, they were firmly under Australian control 44.

The commissioning of the Royal Australian Navy operational force was not the result of any single event or decision. The concern of the people of an island continent, isolated in a hemisphere of alien races, apprehensive of major power competition and conflict, and mistrustful of Britain’s sense of commitment and priorities, must inevitably have led to an independent capacity for naval defence. Imperial opposition, lack of unanimity on the real source of threats, variable public support and lack of funds clouded the issues and delayed fulfilment of early federal initiatives. As well, the usual competition between the Defence services for preeminence and even a considerable variety of opinion within each service also featured strongly as ingredients of political vacillation. But several notable features provided the necessary impetus to achieve the final result: Deakin’s conviction of the threat from Japan, Creswell’s doggedly persistent efforts, and the generally bipartisan political attitude to defence, which enabled the process of transformation of decisions in principle to actuality to survive changes in government.

The watershed in the progression to naval autonomy was the Imperial Defence Conference of 1909, where Australia’s uncompromising attitude forced British Government and Admiralty acceptance of the inevitability of the establishment of an Australian navy. Although there were subsequent imperial regressions on agreements reached at this Conference, the formation of an Australian naval force survived, both in physical realisation and in retention of its control by the Australian Government. The 1909 Conference sealed the pattern which successive Commonwealth governments followed through to establishment of the Royal Australian Navy.

Notes

1. G.F. Pearce, Minister for Defence, retrospectively in 1913 (Macandie G.L. The Genesis of the Royal Australian Navy Sydney 1949 p272).

3. Meaney N. The Search for Security in the Pacific 1901-14 Sydney 1976 p27.

5. New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings (1883-4) Vol IX p13-14.

6. Commonwealth of Australia Parliamentary Papers (CPP) (1901-2) Vol 2 No 31 p2; Parliamentary Debates (CPD) (1903) Vol XIV p1773; Macandie RAN p42, 57.

7. Reynolds J. Edmund Barton Sydney 1948 p75-7.

8. CPP (1901-2) Vol 2 A12 ‘Naval Defence of the Commonwealth of Australia’ p4 paragraph 4.

9. CPP (1901-2) Vol 2 No 31, ‘Memorandum of the Colonial Defence Committee’ p3.

10. CPP (1901-2) Vol 2 A36 ‘Minute upon the Defence of Australia by Major General Hutton, Commandant, 7th April 1902’ p1.

11. CPP (1901-2) Vol 2 No 52 ‘Report by Captain Creswell on the Best Method of Employing Australian Seamen in the Defence of Commerce and Ports’.

12. Meaney Search for Security p84.

13. Macandie RAN p105; Johnson F.A. Defence by Committee London 1960, p50; CPD 1903 V XIV p1775, 1782, 1784, 1793-4, 1804, 806-7, 1906, 1969.

14. CPP (1905) No 66 ‘Report Submitted by the Naval Director to the Honourable the Minister of State for Defence’ p2.

15. Meaney Search for Security p84.

16. CPD (1905) XXV p811; La Nauze J.A. Alfred Deakin Vol II Melbourne 1965, p448; CPP (1905) Vol II No 31 ‘Views Expressed by the Honourable Alfred Deakin, MP on the Present Condition of the Defence of the Commonwealth communicated to The Herald on the 12th June 1905’.

17. CPP (1906) Vol II No 66 pl-3, No 62 pl2-13.

18. CPD (1906) Vol XXXV p5571-2, 5576.

20. For Creswell’s criticism: Macandie RAN p173-5; his strategic assessment: p179-80.

21. CPD (1907) Vol XLII, p7514-5; La Nauze Deakin p525.

23. Macandie RAN p216-21, 235-6; Meaney Search for Security p179.

24. Meaney Search for Security p180-1; Macandie RAN p237-8; Deakin Morning Post 17 May 1909.

25. CPD (1907) Vol XLII pp75l2-8.

26. Deakin Morning Post 14 April 1908, 17 May 1909.

27. Meaney Search for Security p195.

30. Deakin Morning Post 13 November 1909; Macandie RAN p243.

31. CPD (1909) Vol LI p3615; (1905) Vol XXIX p5546.

32. CPD (1909) Vol LIV p6945; CPP (1914) Vol II No 33 ‘Navies - Relative Strength in the Pacific’

33. Meaney Search for Security p192.

34. CPD (1909) Vol LIV p6259, 6657-8, 6663.

35. CPP (1911) Vol II No 7 ‘Naval Forces Recommendations by Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson’ p24.

36. Deakin Morning Post 22 January 1910; Macandie RAN p246-7, 264.

37. Meaney Search for Security p214-5 and Note 64.

38. CPP 1911 Vol III No 68 ‘Minutes of Proceedings of the Colonial Conference, 1911’ p15, 1x.

39. CPP 1911 Vol III No 12 ‘Memorandum of Conference between the British Admiralty and the Representatives of the Dominions of Canada and Australia, June 1911’, para 1.

40. Meaney Search for Security p226; it is interesting that Johnson Defence by Committee makes no mention of Dominion consultation in the handling of the crisis in the Committee of Imperial Defence (p114-8) but in pushing the ‘drive to secure complete co-operation of the Dominions’ (p120) exposes the reality as no more than ‘sharing of information’ (p121) which took place post-1911, when it happened at all.

41. Marder A.J. From Dreadnought to Scapa Flow Vol 1 London 1961 p279-80; Meaney Search for Security p230, 232, 244.

42. Meaney Search for Security p232, 240.

43. Meaney Search for Security p236, 239, 261.

44. There was, however, the caveat that it should come under British Admiralty control on outbreak of war, which led to most of the RAN coming under its control and being employed in the Atlantic and Mediterranean during World War 1 and the first part of World War 2.

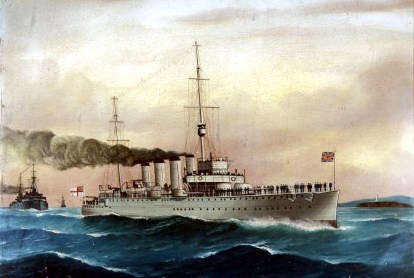

Third Class Cruiser HMS Mildura

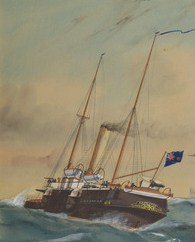

Third Class Cruiser HMS Mildura Torpedo-Gunboat HMS Boomerang

Torpedo-Gunboat HMS Boomerang Torpedo Boat HMS Mosquito

Torpedo Boat HMS Mosquito Battle Cruiser HMAS Australia

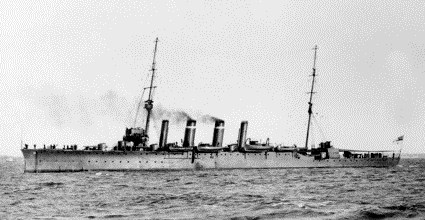

Battle Cruiser HMAS Australia Light Cruiser HMAS Sydney

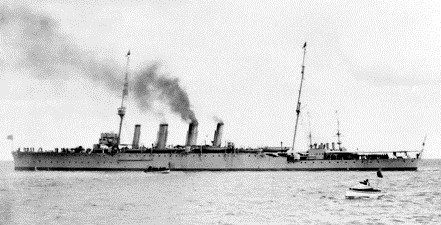

Light Cruiser HMAS Sydney Light Cruiser HMAS Melbourne

Light Cruiser HMAS Melbourne Destroyer HMAS Yarra

Destroyer HMAS Yarra Destroyer HMAS Parramatta

Destroyer HMAS Parramatta Destroyer HMAS Warrego

Destroyer HMAS Warrego Initial RAN fleet entering Sydney Harbour 1913

Initial RAN fleet entering Sydney Harbour 1913 RAN ships after entering Sydney Harbour 1913

RAN ships after entering Sydney Harbour 1913