The Federated Ironworkers Association of Australia and the

1939-45 War Effort

Australian contributions to the 1914-18 imperial war effort were principally in raw materials, of which the most significant was manpower – men who were effectively equipped and supplied by the United Kingdom, and employed in theatres of war remote from Australia 1. World War 2 was to see a different picture: a beleaguered and isolated Britain facing crucial shortages and, with the emergence of a direct Japanese threat to Australia, the latter’s need for a total mobilisation of resources together with a higher degree of self sufficiency to cope with the costs and limitations in British and American support for the Australian armed forces 2. In this climate, support for Australian industrial production attained a critical status previously unknown, with the centre of effort in the metals industry – the oligarchic metals corporations and their substantially unionised employees 3, Control of these metal workers at the heart of defence production fell increasingly within the ambit of the Federated Ironworkers Association of Australia. Consequently, the current and future attitudes, and success in advancing those attitudes with the government, employers, labour movement and especially its own branches and members, held one of the keys to the national capacity to contribute to the international war effort in general and the country’s own defence in particular. It is therefore appropriate to trace the approach of the FIA federal leadership and the responses of the organisations and individuals interacting with it, internally and externally, to assess the FIA’s place in Australia’s wartime economy.

By the close of the 1930s, the FIA and its members were in the process of recovering from the depression, a position which they shared with workers in other industries. The restoration of pre-depression employment levels had enabled the Miners Federation to embark on a round of industrial action which saw the reinstatement of pre-depression industrial conditions 4. Such a lead was attractive to other major unions, where this climate of growing militancy gave scope for the advancement of activist communist candidates to trade union leadership. This advancement was also facilitated by the flexibility allowed to Communist Party of Australia members by the Seventh Comintern decision to discard its monolithic stance, seeking influence in each country through fronts which could exploit local issues 5. With an apparent independence from Moscow, freed of the single-policy, antisocialist albatross, and able to make realistic compromises, CPA members could assume a degree of respectability which, allied to their energy in promoting: workers rights and libertarian issues, made them attractive candidates for senior union leadership positions. Ernest Thornton had gained election to the crucial FIA general secretaryship in 1936 6, and flowing from the successful activism which followed, by 1940 communists held effective control at federal and branch levels 7. With this degree of control, the way was open for the communist leadership faction to promote the interests of it own cause as long as it maintained its hold of the important offices.

The communist cause was essentiality a Sovio-centric one. The CPA had established itself as the official party in 1922 through Comintern recognition 8, and consequently owed that body its primary allegiance. But although the 1935 Comintern Conference had allowed a degree of devolution of policy to national parties, this new realism was really the product of the Comintern’s subservience to Soviet Union foreign policy interests 9. Alarmed at the resurgence of Germany, the USSR was determined to organise an anti-fascist front, from which arose the overt international policy of collective security in which a coalition of the major powers would guarantee to align against any aggressor, whether external or one of their own numbers 10. This cooperative security dogma consequently gave the CPA, and in extension, the CPA faction in the FIA leadership, its theme for relations both nationally and in the workplace. The theme is clearly reflected in the FIA’s Federal Committee of Management decisions on 21 October 1939 which endorsed support for cooperative security and peace, whilst directing all branches to continue normal industrial activism regardless of the war 11. The FIA leadership was at this stage still apparently uncertain of how to handle the Soviet switch from cooperative security to a non-aggression pact with Nazism. However, at very least it recognised that the Anglo-French alliance was alien to this pact. In consequence, war production in support of that alliance was by definition similarly hostile, so it felt safe in continuing with industrial militancy, raising the very plausible spectre of the World War 1 experience of employers using the war effort as a control on workers’ conditions 12. Subsequent confrontations with metals employers and support of the miners’ strike were pursued on this basis 13.

Resolution of the quandary arising from the expedient Soviet policy of accommodating Hitler caused some heart burnings to the communist theorists as well as the practitioners. A looming war, involving a triangle of capitalist, fascist and socialist powers, for which the cooperative security formula had been devised, had now become a fascist-socialist alliance existing in parallel with a fascist-capitalist war. The only feasible solution was to shift the principal odium to the capitalist powers. So the thrust of this repositioning was exhibited in Thornton’s amendment to the ACTU’s April 1940 resolution on the war effort 14. His amendment sought to label the war as a continuation of the World War 1 capitalist struggle for colonies, markets and raw materials, oppression of the working class and a conspiracy to divert fascism against the USSR. As an imperialistic capitalist war it held no claim on Australia’s working class, which should work to retain its civil liberties and living standards, end hostilities, withdraw Australian troops and cooperate with the USSR 15. Although Thornton was defeated in both his bid for the ACTU presidency and in this amendment, the vote was close 16. But he did have his way in the FIA Federal Council meeting of April 1940 where the ACTU support of the war was condemned 17. And in furtherance of its anti-war stance, the Council also affirmed its opposition to the expanding scope of the National Security Regulations and Australian Workers Union pro-war sympathies, whilst expressing support for anti-conscription campaigning and the Council for Civil Liberties 18.

In line with this recasting of the scene as an imperialistic war, the Australian federal government had to take its place in those ranks, which upgraded the standard position of the UAP-CP coalition as employers’ puppets 19 to that of junior partners in an international capitalist conspiracy 20, This left the FIA policy cupboard somewhat bare when it came to influencing its members on support of political parties. Whilst the conservative coalition could be satisfactorily put down as capitalist imperialists oppressing working class living standards and liberties, the ALP opposition was also heavily tainted in supporting an imperialist war effort at the expense of national and international working class solidarity 21. The best that it could do for the September 1940 elections was to urge members to vote against Menzies 22. Earlier, the June edition of the Ironworker had attacked the Prime Minister’s plea for major union cooperation 23, following this up in July with a tilt at the ACTU for accepting the invitation to negotiate on participation in advisory panels aimed at facilitating trade union support of industrial productivity 24. While the FIA declaimed that cooperation with a director general of munitions supply who was also the chairman of BHP would be tantamount to cooperation with their traditional enemy, ACTU endorsement of the panels left the FIA Committee of Management with little option but to give grudging assent to cooperation, covering this retreat with fulminations against the government, the bosses and the National Register 25. However, the Committee had no intention of facilitating a dirty war – whilst the necessary formalities of the panels were observed as an unavoidable facade of responsibility, the reality became apparent as a wave of strikes spread throughout the country.

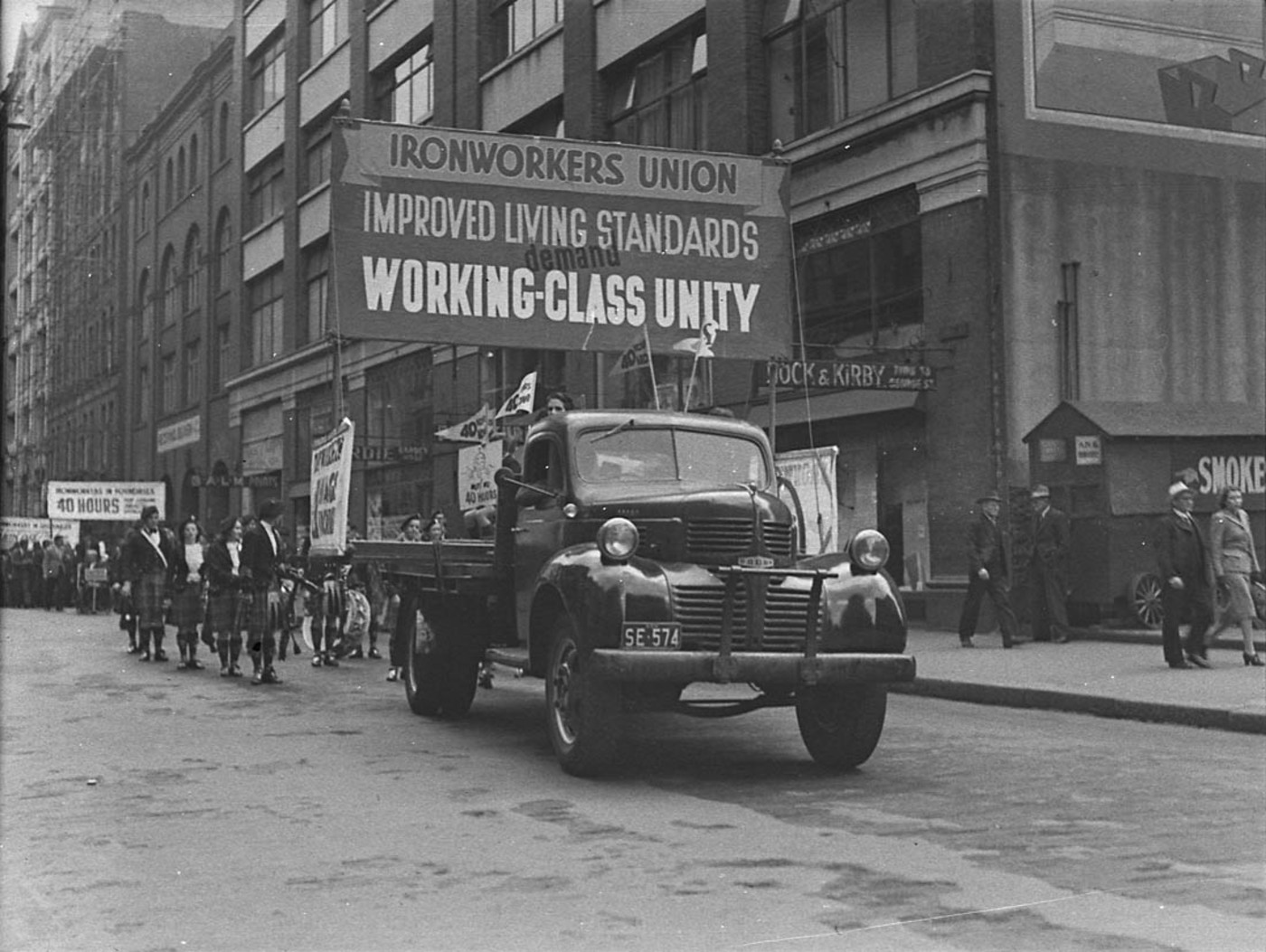

This broadly based strike psychosis could not be seen as a specific attempt to damage the war effort: the trade unions, which were either controlled or heavily influenced by communist leaders, simply owed nothing to the war effort, but certainly did have some longstanding scores to settle. Although most had recovered the depression losses by 1939 26, this left workers with no appreciable gains in living standards for a decade 27. What they did have was an enhanced bargaining position as the traditional unemployment pool evaporated and demands on production escalated with the growing seriousness of the war 28; and also the wry satisfaction of a direct reversal of the depression situation which had forced their acceptance of earlier reversals in conditions. Militant leaders had nothing to lose by industrial action, but much to gain in enhanced conditions for their members and, by reflection, enhanced personal reputations and grass roots support.

The return of the coalition government in September 1940, together with a high tax budget which could be portrayed as directed against workers, gave added grounds on which to stir up membership support 29. Yet although in November 1940 the Ironworker was depicting a national strike wave 30, the trade union movement was not so united. The ACTU under Albert Monk’s leadership was doing its level best to maintain industrial peace where this was warranted, and this with the cooperation of the more moderate unions. For one, the Australian Workers Union was not the turbulent self of its earlier days, determining to make a reasonable attempt towards cooperation in maintaining industrial harmony and production, including efforts to use its good offices in restraining disruption from other unions represented in the same workplaces 31. This brought the AWU into collision with its rival, the FIA which, bent on resisting further AWU pirating of its own membership and in maximising its gains in conditions while the industrial climate was favourable, accused the AWU of acting to break a strike at Port Kembla, discredit the FIA and curry favour with the employers and State Industrial Commission 32. Undaunted by the lack of trade union solidarity, the FIA continued its campaign through the first half of 1941. Moves to deregister the union were initiated in Victoria in April 33, and there was every prospect of continuing industrial confrontation in which, with the historical weapons of lockouts and scab labour increasingly denied to the employers, the prospect looked set fair for further Union victory.

This victory was preempted by another. Germany’s June 1941 invasion of the USSR forced the Red Army back to the outskirts of Moscow, and survival of the homeland of socialism was at risk. Although the war had abruptly lost its imperialist character, Australian communists were temporarily lacking a new direction 34, and a new direction was certainly needed. The June ACTU Congress had seen an FIA-supported Sheet Metal Workers Union counter resolution to the ACTU Executive’s proposed continuation of support to the war effort, a move which denounced British, French and American imperialism against working class and Soviet interests as well as roundly condemning Australian government actions in support of the war 35 The FIA delegates had also added demands for collective union militancy and a reaction against war production propaganda which only favoured profiteers 36. However, a change was heralded in a subsequent leading article of the Ironworker which tentatively broached the subject of ending strikes conditional on an end to ‘private profit and greed’ 37 – a small beginning for what was to become a major about face in the Union’s approach.

The Anglo-Soviet Pact of June 1941 placed the United Kingdom as firmly in the Soviet camp as Hitler’s invasion had taken Germany out of it. So the nature of the war had to be redefined: fascism was the enemy and the enemies of fascism were friends. The war against fascism demanded maximum international support, and consequently the FIA federal leadership was to throw its full weight into promoting such support 38. Yet whilst the new turn to the war could justify a change in Union attitude, the Menzies government was too well established as the enemy of the working class 39 for the Federal Committee Management to be able to offer it cooperation on the scale which was now envisaged. A war against fascism could not be prosecuted effectively by an administration so tainted with pro-fascist sympathies; a demonstrably anti-fascist government was needed to support a now respectable Britain in consort with the USSR: Menzies must go 40.

The alternative was, inescapably, the ALP whose support for the war was not so compromised, who indeed had spoken out against the use of the ‘red bogey’ in parliament 41. With the social-fascist tag buried, Thornton worked up a consortium of big unions in the maritime and metal industries, which offered to Curtin their efforts to ‘mobilise and use Australian resources to defeat the Nazis’ 42. The FIA Federal Committee of Management confirmed its support of this offer, giving production priority over all other issues 43, and with this new relationship given practicality by Labor’s accession to federal government in October 1941, the stage was secured for uninhibited support for a progressive government against the fascist axis 44. The leaderships of the key unions knew their task. They now had to convince union members of their new duty and divert the previous militancy, which they had encouraged, towards sustained productivity.

Thornton had not waited for his Federal Committee of Management’ s October public call for unity against Nazism or for the advent of the Labor government before beginning his own action. Immediately after the CPA decision for all out support of the Anglo-Soviet Pact and the war effort 45, the Ironworker of September 1941 attacked the ‘disease of militant unions’, condemning irresponsible strikes which were attributed to new members, and as a lead in to tighter control, demanding absolute union discipline. Hard on the heels of this move came the Thornton-organised offer to Curtin, and it was not until the following month that this dramatic policy shift was submitted to and approved by the Federal Committee of Management, a strong comment on Thornton’s confidence in the solidarity of support which he could expect to muster. As he said in his report which was taken at that meeting, there were probably more communists and their supporters in the FIA than in any other union in the country 46. And with full Council backing, he was able to press forward with a hard line campaign to mobilise the Union and pressure government and other unions into unreserved commitment to the war effort and support of the USSR 47.

The principal technique of this union control was not a new one, having been adapted by the CPA from Comintern democratic centralism 48. Members’ rights, although acknowledged in an overlay of ritual statements on working class liberties and living standards, were to be sacrificed on the altar of maximised production 49. Within the FIA, the duty of members and branches was to carry out the instructions of the federal organs, which continued to condemn unauthorised and irresponsible strikes, the evil of absenteeism and disruption caused by members misleading union officials into unnecessary disputes with management 50. Thornton put the whole matter of the task of unions into perspective in his pamphlet The Unions and the War Effort which took the campaign beyond the straightforward organisation of his own union into the area of lobbying other unions and government along the same path of single-minded support of maximisation of productive effort 51. The various threads of pro-war, pro-Soviet policy developed into a coherent form which was, belatedly, accepted by the FIA Federal Council meeting in mid 1942: defeat of the Axis, support of the Anglo-Soviet Treaty and United States participation, the opening of a second front that year, commendations of the Labor government, legalisation of the CPA and maximisation of defence production 52. Similar policy objectives were endorsed by major trade unions involved in production and distribution and, at the upper echelons at least, the country was now wholeheartedly behind the war effort 53.

At lower levels there were some who were not so sure. Whilst it would be uncharitable to accuse the Thorntonites, staunch internationalists though they were, of not having any concern for Australia’s own national safety in the face of the Japanese threat 54, there is little doubt that the main initiating and continuing impetus for their dedication to the war effort was the Axis threat to the USSR 55. But reaction within the Branches was mixed. The long ingrained attitudes and practices on the shop floor of workers’ struggle, and some of the branch leaders’ philosophical approaches, were not amenable to such a dramatic change in policy. The rank and file belonged to a union essentially for the benefits which it conferred on them: the increase in FIA membership from 10,000 to 29,000 56 over the previous five years was largely a measure of the union’s success in not only retrieving the losses of the depression but also in surpassing previous levels 57. The methods used had blatantly exploited the situation where employer and government urgency to maintain war production had inhibited their flexibility in countermeasures and resistance to union demands and action. FIA leadership was able to exploit this weakness in good conscience from its doctrinaire opposition to the capitalist’s war; as a consequence the General Secretary was able to report with considerable satisfaction in May 1941, on the eve of the German invasion of Russia, that the previous year had seen ‘the greatest wave of strikes yet known in the history of our Union’ 58. These were heady heights to descend from; confrontation had given members double the wage increase which they might have expected yet they were now admonished by the selfsame leadership on the scourge of militancy 59. The nuances of what was capitalistic and what was patriotic were too subtle for the uninitiated and for those whose patriotism was not synonymous with the interests of the Soviet Union. Whereas many might previously have been persuaded to ignore ALP and ACTU support of the war effort in favour of self interest, to now change to that policy at the expense of self interest was too much for those not susceptible to the underlying dogma.

Imposition of the federal policy took two forms – a centrally directed campaign to indoctrinate members, and the use of branch discipline to control and direct members’ activities. The former was evidenced in the regular articles in the Ironworker 60 which all members received, supplemented by Sydney and provincial radio broadcasts, although these latter were inevitably received by and tailored for a much wider audience. The essence of persuasion through these media was a justification of undiluted support for the war 61; the results demanded were increased production and support of institutions friendly to the USSR 62; and the practices denounced were disruption and absenteeism in the workplace 63. As the war dragged on, the difficulties of achieving and sustaining solidarity on these lines became apparent 64, with resort to the disciplinary arm becoming more obvious. Direct disciplinary measures were, however, routinely outside the sphere of the federal officers, so their success or otherwise depended on the attitudes and enthusiasm which were evinced at site level 65.

Such enthusiasm was frequently either non existent or backsliding. The Policy Committee report to the Federal Council meeting in early 1944 noted that some officials and members had reservations on the union policy of minimisation of strikes and maximisation of production, with resulting avoidable disruption that damaged output 66. It also emphasised that, good as the war news was, there should be no complacency, a reflection of the war weariness which was beginning to make itself felt not only in the community at large but also in industries whose union task masters had now been pressing their members for improved productivity for three years 67. Even at the June 1945 National Conference, with Germany defeated and Japan pressed back on its homeland, there was still pressure to maintain the industrial peace to facilitate the war 68. The Union newspaper and radio broadcasts continued to pour out exhortations against disruption and absenteeism, censuring the inadequate and praising the dedicated and disciplined 69. But whilst such a well conducted branch as the Newcastle one was commended on its wily undermining of a BHP lockout 70, others had given trouble. Some of this was fairly readily solvable – federal intervention had smoothed out the difficulties and mismanagement in the Victorian, Queensland and Port Kembla Branches 71, but the Balmain Branch had not responded to the Federal Committee of Management’s democratic centralism.

At the heart of this trouble lay the Branch’s long tradition of militancy combined with the political stance of its leadership. Its workplaces were mainly waterfront based, including Mort’s Dock and Cockatoo Island Dockyard. The area was depressed and work facilities inadequate 72 – a natural breeding ground for industrial disputation which was now being instructed by its federal office to set its legitimate grievances aside. The local leaders included N. Origlass and L. Short, whose Trotskyist inclinations 73 ensured that, although they were sympathetic to the USSR as a socialist state, even if a misdirected one, they had no sympathy at all with the Stalinist CPA and its members who dominated the FIA leadership, interfered in their Branch from the top, and subverted it from below. Quite out of sympathy with Federal policy, presented with the perfect opportunity to further their members’ interests, and under personal attack from their Stalinist opponents, the Balmain controlling group persisted in the type of industrial disputation which had long characterised the Branch. The rift between supporters of the local leaders, and the federal leadership and its sympathisers, first favoured the former in the 1942 Branch elections. These were consequently voided by the Federal Council’s Special Meeting on the grounds of irregularities 74, however a re-run gave a clear two to one majority to the local leadership 75, The next elections at the end of 1942 reversed this decision – a result which a majority of members found hard to believe, and one which became more and more resented as the new Branch officials enforced the federal no-disputes policy 76. A similarly dubious result in the 1944 elections brought the situation to a head: Origlass was removed as a shop delegate 77, and the majority of members then retrieved themselves from the control of the official Branch, setting up a separate one of their own and becoming involved in a six week strike in the process 78.

This break away was long in the making – the culmination of three years of repression by a federal leadership intent on enforcing its policy rigidly on an unwilling membership. Whilst this resentment was latent in all branches, the Balmain one was the only one which did not start the ‘support the war’ phase with a local communist leadership, sympathetic to the federal officers, in effective control. With a local leadership around which opposition to federal direction could crystallise, there existed the capacity to organise effective counter campaigns which were intensified rather than crushed by federal repressive measures 79. The federal leadership and its supporters might have done well to examine their own communist revolutionary theory to predict the result of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern which evolved – but in this case, with the communists cast as the oppressors and the working class as their opponents. The fact that workers had become unionists as a way of avoiding oppression rather than submitting to it was reflected in the continuing Balmain dispute and quickly suppressed ones in other branches 80.

Although its energies were strongly centred in controlling its own union, the FIA leadership did not neglect the pressure it could bring on government, the public at large, the rest of the union movement and the armed forces. In any international climate, the Menzies-Fadden governments would have been the target of a working class organisation; the ‘capitalist war’ phase simply gave reason to redouble the vituperation, yet the ALP’s hostility to the CPA and support of the war precluded the FIA hierarchy from positive support for Labor. Rather, political activity was on negative lines – the ousting of the pro-imperialist government. The Union’s switch in favour of the war effort made the existence of the UAP-CP government downright embarrassing, and the urgency to remove it left no alternative to wholehearted backing of the ALP under the guise of its new found respectability as a progressive party. When the Curtin administration took over federal government, the FIA was able to offer support without the appearance of selling out working class interests 81, particularly with the now less pernicious use of the National Security Regulations and relief of CPA persecution 82. The FIA was able to recommend that its members seek ALP endorsement for the 1943 elections 83, deal directly with federal ministers in settlement of disputes 84, and even demand that the government intervene against the Arbitration Court for not adopting effective strike prevention procedures 85.

Relations with the ACTU were at best ambivalent. Election of moderate Albert Monk over Thornton in 1940 resulted in early ACTU endorsement of ALP support of the war effort – over a year too early by FIA standards. However, the peak labour organisation could not be ignored, so FIA efforts were directed to upholding those parts of ACTU policy which were useful 86 and attempting to influence and use the ACTU to further its own objectives 87. FIA’s connections with other unions were oriented to encouraging their adoption of policies in consonance with its own, whilst opposing those unions which refused cooperation or competed for membership 88. It sought agreement for harmony of action initially to promote militancy and subsequently to foster industrial peace, through the media of cooperative agreement, amalgamation or absorption 89. The growth of the FIA by a factor of five during the war 90 attests to the success it achieved in expansion, although some amalgamations were unduly protracted 91.

In addition to its extended influence in the trade union movement, the FIA established connections through any front organisation, or for that matter any organisation, which allowed it a platform from which to disseminate its message or further mobilise action and support. Such contacts ranged from the Council for Civil Liberties 92, through the Friends of the Soviet Union and kindred organisations 93, to meetings with children, women and servicemen 94. Whatever reservations might be held on the doctrinal tenets of the union’s leadership, and the ethics of their placing the interests of their members behind those of war production, their patriotic rating was unquestionably high when judged against the attitude of the community in general and other organisations in particular.

After the exit of the Menzies and Fadden governments, the most significant problem in definition of relationships was with the employers. The most imminent and permanent adversary was also their co-partner in production. Here was a tightrope which would challenge the most adept dissembler, to convince the mass of membership to avoid confrontations without appearing to desert the working class cause 95. The intended solution was a delicate balance of sufficient denunciation of the bosses without crossing the brink 96, diverting further pressures and action to the Arbitration Court 97, with the argument on employers’ avarice answered by the government’s control of profits 98. The initial results were gratifying throughout the whole union movement, with Australia-wide work losses falling from a 1940 peak of one and a half million days to 378,000 in 1942. However the majority failed to remain convinced of the dictum of setting everything aside in favour of the war effort, resulting in a steady climb back towards a million days lost in 1944, peaking at 2,120,000 in the 1945 end of war scramble to enter the reconstruction era on a winning run 99.

Impact Assessment

Assessment of the results of the FIA’s attitudes to the war in terms of actual production is difficult to specify quantatively in view of the diversified nature of the industries covered and the lack of product uniformity even at a single work site. The most useful potted output figures are contained in the Commonwealth statistical summaries of metals industry production 100 which are expressed in monetary values; these are summarised in the graph at Figure 1. To allow for changes in money values, the figures have been adjusted by the Wholesale Price Index (Metals and Coal) for each year 101.

The modest increase in the early war years is a product of initial fairly low key government reaction, which was then accelerated by the end of the ‘phoney war’ in 1940, but inhibited by industrial action. The union-cooperation phase saw increasing output until 1944, when a combination of war weariness, grass roots restiveness, and shortfalls in coal supplies saw a falloff in production and a shortage of iron and steel products 102.

When this is allied to the specific information on FIA activities, there is a clear parallel of the Union’s federal attitudes towards the war and patterns of disputation, efficiency and absenteeism. There is also the disaffection which disrupted production and called down interference from the federal officers in an effort to maintain discipline and sustain flagging enthusiasm. This reaction to backsliding is evidenced not only by the strength of reaction to the Balmain revolt, but also in the increasingly authoritarian tone of the exhortations to branches and in the uncompromising resolution in keeping up productive effort in the last two years of the war, even on the eve of the defeat of Japan when post-war issues were demanding primary attention.

All this makes it abundantly clear that, for the second half of the war, and from Australia’s point of view the most critical one, a conjunction of factors worked well in its favour towards promoting an effective defence effort. Although they were general in effect, the components are demonstrated very plainly in the FIA’s activities when the communist-dominated leadership was turned by Soviet involvement in the war to unremitting support of defence production and of the overall war effort. And this support was facilitated by the advent of a visibly ‘progressive’ Labor government, together with the direct threat from Japan which convinced doubters of the USSR cause that it was now indeed a patriotic war. The FIA leaders, in fulfilling their obligations to both international communism and to their objectives in Australia, were unrelenting in enforcing a central control, which overrode the rights of branches and members, in a drive to suppress the militancy which they had promoted and the slack work habits which they had at least tolerated. Finding such deeply ingrained habits hard to eradicate amongst those less dedicated then themselves, they resorted to all necessary expedients to entreat, cajole and enforce sustained productivity, postponing the working class struggle to a time when the battle lines of that war could once more be clearly defined. The effect was fortuitous for Australian and allied defence production. But had the Soviet Union not been compelled to fight the German-Japanese axis, or indeed had actively committed itself to that side, it is not difficult to imagine the union action which would have crippled rather than buoyed the Australian war effort. It was indeed a fortuitous conjunction of circumstances.

[Minutes, Correspondence, Broadcasts, Press Statements and Union publications quoted are from the FIA deposits at the Archives of Business and Labour of the Australian National University]

1. Commonwealth of Australia Parliamentary Debates (CPD) (1940) vol 163, p 62,119; E. Scott Australia During the War 1914-1918 p 234, 248.

2. CPD (1940) vol 164, p 16-7; S.J. Butlin War Economy 1939-1942 p 5-6; Sydney Morning Herald 8 June 1940, p 16; 15 June 1940 p 14.

3. J. Hagan The History of the ACTU Melbourne 1981, p 65; Tribune 1 July 1942, p 6.

4. R. Gollan The Coalminers of New South Wales Melbourne 1963, p 213-4.

5. ‘Teach the Masses – Learn from the Masses’ Communist International January 1936, p 16.

6. Minutes, Federal Council (MFC) 24 April 1936, p 30.

7. Whilst as late as 1941 Thornton was careful to maintain the image of cooperation with non-communists in union leadership (General Secretary’s Report 8 October 1941, p 5 - attachment to Minutes, Federal Committee of Management (MFCOM) 9 October 1941), he was later quite straightforward in stating ‘the policy of the Ironworkers Union is decided in consultation with the leaders of the Communist Party’ (E. Thornton ‘Unions and the Party’ Communist Review July 1948, p 208). There was a mixture of bravado in open admission of communist office holdings (Broadcasts 3XY, 26 August 1943) and discretion in denial of communist control (Press Statements 19 May 1945).

8. A. Davdson The Communist Party of Australia Stanford 1938, p24.

9. F. Borkenau The Communist International London 1938, p386, 394

10. R. Dixon 'R. Dixon Replies to G. Crane' Communist Review p33.

12. Ironworker November 1939, p1

13. Ironworker 28 February 1940, p1; March 1940, p1; December 1940, p2

14. Ironworker April 1940, p3;

15. Ironworker April 1940, p3; cf J.D. Blake 'The ALP and the Present War' Communist Review December 1939, p715, 717, which enunciates the ideological background for this position.;

18. MFC 24, 27 April 1940, p6, 7, 10; Ironworker May 1940, p1, 4.

19. MFCOM 7 December 1940, p5.

21. Ironworker May 1940, p1, 4.

22. Ironworker September 1940, p1; however, after return of the UAP-CP coalition, there was a realisation of the need for something more positive in the resolution that the Labor Party should be called on to fight for anihilation of the government (MFCOM 7 December 1940, p5).

25. MFCOM 17 July 1940, p1-2; Ironworker July 1940, p4.

26. R. Gollan Revolutionaries and Reformists Canberra 1970, p70.

27. Ironworker September 1940, p1, 4.

28. Sydney Morning Herald 8 June 1940, p16; 10 June 1940, p10; 15 June 1940, p10; 15 June 1940, p14.

29. Ironworker December 1940, p1, 3; January 1941. p1, 3; February 1941, p1, 6.

30. cf SMH 9 November 1940, p12.

31. MFC 27 April 1940, p10; Ironworker December 1940, p4; February 1941, p4; SMH 16, 17 January 1945, p4 and p2.

32. MFCOM 7 December 1940, p4.

33. Correspondence Secretary Victorian Chamber of Manufacturers to FIA of 20 March 1941; Ironworker 19 April 1941, p1.

34. Thornton's immediate reaction was disbelief the Britain and the USSR could make an alliance work (Press Statements 23 June 1941.

35. Ironworker July 1941, p1; MFC 26 May 1941, p9.

38. MFCOM 9 October 1941, p2: E. Thornton The Unions and the War Sydney 1943, p4.

39. MFCOM 9 October 1941, p5; MFC 26 May 1941, p9.

40. Ironworker August 1941, p1.

42. Correspondence Thornton to Curtin of 17 September 1941.

44. Correspondence Thornton to Curtin of 11 November 1941.

45. SMH 17 July 1941, p11 Statement by L.L. Sharkey.

46. General Secretary's Report of 8 October 1941, p5 - attachment to MFCOM 9 October 1941.

47. Correspondence telegram General Secretary to Curtin of 10 October and 10 December 1941; see also Note 44 above.

48. The FIA leadership had begun action for centralisation in 1940 using the claim that government was exploiting federal/branch divisions (MFCOM 6 December 1940, p3); this was translated into specific power by centralisation of union appeals (MFC10 December 1942, p9) and finance (MFC 27 January 1944, p3).

49. MFCOM 9 October 1941, p3; Ironworker February 1942, p3; Broadcasts 2KY 24 October, 24 November 1942.

51. Thornton Unions and the War p9, 12-13.

54. Ironworker April 1942, p1.

55. Correspondence telegram General Secretary to Curtin of 10 October 1941; Ironworker March 1941, p4; MFCOM 9 October 1941, p2; MFC 16 June 1942

56. MFC 2 May 1938, p4; Correspondence Statutory Declaration by General Secretary of 19 May 1941.

57. Ironworker November 1940, p1, 4.

58. General Secretary's Report of May 1941, p1 - Appendix to MFC 19-21 May 1941.

59. Ironworker September 1941, p4.

60. eg November 1941, p4; January 1942, p1; April 1942, p6; August 1942, p6.

61. Ironworker November 1941; February 1942, p3; August 1942, p6; Labor News March 1944, p2.

62. Broadcasts 2KY 22 September 1942; Broadcasts 2KO 16 July 1942; Broadcasts ABC 22 December 1944; Ironworker September 1941, p1; January 1942, p1; February 1942, p3, 5; Labor News November 1944, p1.

63. Broadcasts 2KY 22 November, 20 October 1942; Broadcasts 2WL 18 December 1944; Ironworker September 1941, p4; Labor News August 1945, p1.

64. Broadcasts 2KY 20 October 1942; Broadcasts ABC 22 December 1944; MFC 3 February 1944, p25; Minutes National Conference 19 June 1945, p18.

65. MFCOM 12 January 1943, p1; Labor News September 1943, p3; November 1943, p1, MFC 3 February 1944, p26.

67. MFC 3 February 1944, p25; this was followed up in the March edition Labor News (p5) with an article patiently explaining why members should 'work all out'; for examples of pressures applied see Minutes, Balmain Branch Management Committee 14 December 1942, p1; MFCOM 7 August 1942, p1.

68. 'The Present Situation and Next Tasks' Communist Review August 1945, p578.

69. Labor News November 1944, p1; August 1945, p3; Broadcasts 2KO 17 December 1943; Broadcasts 2WL 8 December 1944; Broadcasts ABC 22 December 1944; Press Statements 12 April 1945.

70. Labor News January 1944, p1.

71. MFCOM 7 December 1942, p1; 21, 22 April 1943, p4, 7: MFC 23 September 1943, p6.

72.Minutes, Balmain Branch Management Committee Executuve Meeting 7 July 1942 Resolution; D. Golan 'the Balmain Ironworkers Strike of 1945' Labor History (1972) No 22, p28.

73. Labor News September 1943, p3; May 1945, p1.

74. MFC Special Meeting 9 December 1942, p6

75. Ironworker January 1942, p8.

76. The reversal was preceded by federal intervention which deposed the Branch officials and appointed its own nominees, who presided over

77. Labor News May 1945, p1; Origlass' threatened breakaway group forced the federal officials to remove him as shop delegate; he then applied unsuccessfully to the Arbitration Court for reinstatement.

80. FCOM 12 January 1943, p1; MFC 21 April 1943, p1.

81. Respectability was conferred by plaudits for the ALP government (MFCOM 12 March 1943, p1; 3 February 1944, p25; Tribune 1, 8 July 1943 (p3) and appeals for working class unity (Correspondence General Secretary to Acting Secretary ACTU of 20 November 1941).; Ironworker December 1941, p2; September 1942, p1. Under this umbrella, full support could be given to the ALP at elections (Broadcasts 2WL 26 July 1943; Labor News July 1943, p1; MFCOM 8 July 1943, p6)

84. Ironworker January 1942, p1; October 1942,p1.

85. MFC 16 June 1942, p1; October 1942, p1.

86. MFC 27 April 1940, p10; Ironworker July 1941, p1; January 1942, p1.

87. MFC 6 June 1942, p19, 20; Correspondence General Secretary to Secretary ACTU of 22 April 1941; left wing pressure dominated the 1943 ACTU Congress, with a drift from the official electoral ticket (Tribune 1 July 1943, p3).

88. Correspondence General Secretary to Acting Secretary ACTU of 20 November 1941; Broadcasts 2CY 20 October 1942; see also Note 32 above.

89. MFC 28 October 1935, p1; 16 June 1942, p20; MFCOM 9 October 1941, p7; Ironworker February 1943, p1; E. Thornton Stronger Trades Unions Sydney 1943.

90. MFC 2 May 1938, p4; 15 June 1945, p23.

91. For the saga of federation with the Arms, Explosive and Munitions Workers Federation, compare MFC 23 October 1944, p8 with Ironworker April 1943, p1.

93. MFC 15 April 1936, p5; the international political lines were dominated by persistent demands for a second front in Europe, even in the midst of the Japanese thrust through South East Asia towards Australia: Correspondence telegram General Secretary to Curtin of 10 October 1941; Ironworker January 1942, p1; August 1942, p1; Ironworker January 1942, p1; August 1942, p1; Labor News October 1943, p8; Broadcasts 2KO 27 August 1943.

94. MFC 16 June 1942, p24; organisation of women workers was a growth industry and potential source of Union strength (Broadcasts 2KO 16 July 1943; Ironworker February 1943, p6; Labor News July 1943, p8; the connection with servicemen was largely defensive, attempting to translate RSL demands for 'preference' into 'reinstatement within the security of full employment' (Ironworker June 1943, p7; Labor News November 1944, p12; February 1945, p1; Broadcasts 2KO 19 November 1943; Broadcasts 2WL February 1945).

95. Hence Ironworker February 1942, p3 and August 1942, p6.

96. Usually combining this with an effort to present the later stoppages as a result of employer manoeuvering (Broadcasts 2WL 18 December 1944; Labor News January 1944, p1; E. Thornton Steel Enquiry, AIS Port Kembla Sydney 1943, p16.

97. Broadcasts 2KO 8 October 1943; MFC 16 June 1942, p21.

98. General Secretary's Report of 8 October 1941, p3 - attached to MFCOM 8-10 October 1941; Ironworker December 1941, p2.

99. Butlin S.J and Schedvin C.B. Australia in the War of 1939-1945 Series 4 vol IV War Economy 1942-1945 Canberra 1977, p372

100. Commonwealth of Australia Quarterly Summary of Statistice No 167, 1942 p11; No 179, 1945 p11; No 191, 1948, p15.

101. Quarterly Summary of Statistice No 179, p70; No 191, p94.

102. Butlin and Schedvin War Economy p424; H. Hughes The Australian Iron and Steel Industry 1848-1962 Melbourne 1964, p143.

.jpg)