Chapter 1

Movement and Transportation

In modern military parlance, combat power is the product of firepower and manoeuvre. At lower tactical level this means manoeuvring combat units, but at higher tactical and strategic levels it means moving fighting formations and their support to and within theatres of operations. Wars fought beyond early inter-city strife meant moving armies and providing for their sustenance: while the hordes of folk movements moved and sustained themselves from the land as a natural means of operation and indeed existence, expeditionary armies needed a properly planned and controlled transport system to enable the forces to move effectively, and be sustained, on the way to, during and returning from operations.

While the outcome of such planning and control is apparent in the conduct of many operations, it is also apparently deficient in the failures of many others. At any level, the mobility and sustainment component provides the facilitator without which armies revert to the primitive constrictions which would negate advances in weaponry and firepower. Like all elements of logistics, the movement and transport aspect is intrinsic to the effective deployment and employment of forces.

Historical Example: Wellington in Iberia

In considering the mechanics of movement and transport, it is convenient to recognise the strata which control and execute movement. For efficient planning and supervision a Movements Staff is positioned with the other staffs – Operations and Plans, Personnel, and Logistics – at each level of headquarters, so that the movement requirements of any and every activity are built into activities from the beginning and throughout the implemetation of the activities, rather than added as an afterthought or resurrected when things go awry. Momenent plans require an executive staff to implement them, requiring Movement Control staff at all levels where movement beyond unit capability is is executed. And the movement itself is carried out by transport operators – military, public and commercial 1.

The transport modes now available encompass Railways, Sea Transport, Inland Water Transport, Water Transport, Terminal Operating, Military Forwarding Organisation, Postal Service, Road Transport, Air Transport and Air Delivery. Each has specific capabilities and limitations, and it is the function of the Movement Staff to identify and allocate the mix of modes required for any particular operation; Movement Control engages and directs the efforts of the transport agencies. From even primitive times, successful conduct of military operations has been dependent on the capability to move and sustain forces, and this has required the basic planning, control and execution functions to be integrated into the commanders' plans and carried out by available transport under military supervision. Regardless of the structures and terminology used over the centuries, effective control and action has laid the basis for success; its absence has underwritten failure 2.

Development of Transport Support

In simpler times, before the advent of industrialised warfare in the 20th Century, the demands of warfare were very much less, but in proportional terms against the means of transport available, they were often even more testing and inhibiting on campaigning. Before the 12th Century CE introduction of the horse collar, draught animals pulled with either a chest band or throat-girth which constricted their breathing, so the traction of two horses was half a tonne, as opposed to the the collar rating of a single horse at one and a half tonnes 3. While the horse collar was revolutionary in multiplying capacity sixfold, for any extended distance the animals would still consume their load en route.

King Xerxes I 519-465 BCE

Xerxes the Great ruled the Persian Empire 485-465 BCE.

Xerxes the Great ruled the Persian Empire 485-465 BCE.

He inherited his father Darius’ project of subjugation of mainland Greece to establish an ethnic frontier in the west, but lost his fleet, and its dominant amphibious and essential logistic capacity, at the naval battle of Salamis 480 BCE.

With his resupply eliminated, he had to take half his army home and so lost the land battle at Plataia the following year.

King Alexander of Macedon, The Great 356-23 BCE

Alexander tutored by the philosopher Aristotle and trained to military affairs from his youth by his father King Philip II of Macedon. After his father's assassination he was elected king in his place, took on his father's position as hegemon of Greece, and set about implementing his father's plan and preparations for conquering the Persian Empire, launching his campaign in 334 BCE at the age of 20.

Alexander tutored by the philosopher Aristotle and trained to military affairs from his youth by his father King Philip II of Macedon. After his father's assassination he was elected king in his place, took on his father's position as hegemon of Greece, and set about implementing his father's plan and preparations for conquering the Persian Empire, launching his campaign in 334 BCE at the age of 20.

Although short on financs and without an effective navy, he went about it in a methodical manner, ensuring his rear was secured by spending three years reducing the port cities of the eastern Mediterranean to eliminate the Persian fleet. After defeating Persian armies in three battles, he continued his reduction of the Persian Empire as far as India. Operating across the Asian land mass, his progress was timed to coincide with local harvests to feed his army and its animals.

He died in in Babylon of malaria, which preempted his plans to turn west and conquer Italy and Carthage.

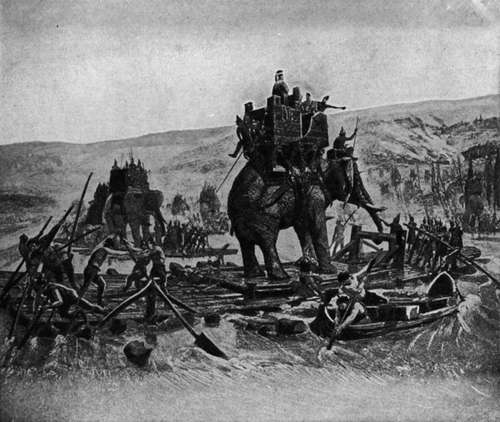

While armies attempted to live off the land – eg Alexander the Great's movements in his campaigns against Persia were defined by the upcoming harvest in the target areas – sustained campaigning was rarely possible, conditional on water transport which could deliver more supplies faster. As an example, Persian King Xerxes' invasion of Greece 480-479 BCE was dependent on both the amphibious capacity of his fleet and the sustainability from his cargo shipping. When his war fleet was defeated at Salamis, he could no longer pose the amphibious threat which kept the Greek armies at home defending their cities, nor protect his supply fleet. Unable to sustain his army, he had to take half of it home, and without the amphibious threat, the Greeks were able to concentrate and defeat the remaing half 4.

Armies continued to be inhibited by their land transport, having freedom of action only where there were waterways which they could also control. An alternative to this had to await the development of railways from the second half of the 19th Century, where a combination of rail and water transport provided a multiplier in movement which could deploy and sustain armies and permit the escalating consumption demands of increasingly sophisticated armies and their support. With the echnological advances of the 20th Century, the development of motor transport and aviation progressively and increasingly added major dimensions to the movement spectrum and capability, both matching and enabling the dramatic advances in the industrial warfare which characterised the major wars of the century 5.

As an island nation, Britain could rely on a strong naval shield to cover home defence, however with interventions in Europe and an expanding empire, its land forces increasingly came to rely on movement agencies to lodge and sustain its expeditionary forces and garrisons.

Commissariat - Treasury/military 6 Xxxxxxxxxxxxxx 7.

Commissary Andrew Miller 17xx-1790

Appointed Commissary of Stores and Provisions to the settlement at Botany Bay, he arrived with the First Fleet in 1788 and also acted as secretary to Governor Phillip.

Ill health forced his replacement in 1790 - his successor was John Palmer, purser of the Sirius - and he died on the voyage home.

Miller was held in high regard by Phillip, who reported that he 'discharged the trust reposed in him with the strictest honour and no profit '.

The First Fleet to establish the military station at Botany Bay was accompanied by Commissary Andrew Miller who had the authority to draw unlimited bills on the British Treasury to provide the transportation and supply support necessary to sustain the colony beyond its own limited resources. His successors and their delegates continued to provide this vital support without interminable delays in seeking approvals at higher levels at home, simply having to justify and account for their actions after the problems were solved. This virtually unlimited capacity to provide support enabled the British forces in Australia to function, and was carried on with the Australian forces at home and overseas through into the 1970s when unthinking generals allowed bureaucrats to place silly monetary delegation restrictions on movement officers executing approved plans 8.

Xxxxx xxxxx 9.

As Britain began to take realistic stock of the costs of providing protection for its empire, it determined that the more advanced colonies should contribute to their own defence. In 185x the Australian colonies were levied a charge of Lxx for each infantryman, Lxx for cavalrymen and Lxx for xxxxxx 10. Faced with this, the colonies, which had hitherto maintained a voracious appetite for more imperial troops, considered how they might minimise the expense to their revenues and began to develop their own land forces in the form of volunteers and militias. As these forces grew over the next 50 years, they required increasingly specific and sophisticated requirements for logistic support.

The colonies had begun to establish their own commissariats under various names to carry out the supply and transport functions for their own civil administration. NSW xxxxxxx; Victoria xxxxxxxx, SA xxxxxxxx WA xxxxxxxxxxx, Queensland xxxxxxx

Commissariat and Transport 11, water transport 12 Railway Staff 12

Lieutenant General Sir E.T.H. Hutton KCB KCMG 1848-1923

His British army service encompassed campaigns in South Africa and Egypt, and he was then appointed Commander of the New South Wales Defence Force 1892-96, during which period he not only revitalised the NSW forces but also promoted cooperation with the other colonies’ forces, and advocated a joint approach to Australian defence.

His British army service encompassed campaigns in South Africa and Egypt, and he was then appointed Commander of the New South Wales Defence Force 1892-96, during which period he not only revitalised the NSW forces but also promoted cooperation with the other colonies’ forces, and advocated a joint approach to Australian defence.

Hutton then moved to command the Canadian militia, which he set about transforming into a national army, followed by service as a mounted infantry commander in the Boer War.

Following Federation he was contracted to command the Australian forces 1902-06. During this period, although hampered by budgetary restraint, he was able to gain control of the drifting ex-colonial forces, and direct their structure and activities to progressing into a balanced national field force.

The colonial forces nominally became components of an Australian army on federation in January 1901, however the absence of a command structure meant that they meandered on as before, with the commandants exercising control and sending the bills to a newly forming Department of Defence in Melbourne. The arrival in 1902 0f a commander of the force Maj Gen E.T.H. Hutton set in place a motivating force for integrating the contingents into a cohesive army, which was however limited by very tight financial restrictions. Hutton quickly produced a plan, however within it there was no provision to extend the transportation services within the limited budget. This budget also restricted his headquarters staff to 13, so he had little room to provide any lavish command and control arrangements, of necessity allocating staff responsibilities according to availability rather than rational groupings.

QMG

DS&T

Railway War Council

Engineer and Railway Staff

Military District Supply and Transport Staffs

Lieutanant Colonel Jxxxx Txxxx Marsh 18xx-19xx

Seconded from the British AASC to at last provide for a director for Supply and Transport and Chief Instructor of AASC Training in 1910, his responsibilities also included Movements. However he failed to provide the direction required, being more content to criticise than improve. State Commandants and British inspecting officers Kitchener and Hamilton didn't agree with his carping about standards of his Corps members.

On the outbreak of World War 1 he managed to organise himself command of the 1 Div Train AASC accompanying 1st Division to Egypt and then France. His service continued to be undistinguished.

The first real test of the fledgling transportation system was in mounting the movement of the Australian Imperial Force to England for the war in Europe, and the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force to capture German New Guinea. This was immediately setback by the Director of Supply and Transport Captain J.T. Marsh managing to wangle himself a berth in 1st Division, leaving his post just when his services, which included Movements, were most needed. The 3rd Military District ADS&T WO H.E. Heydt, was moved in to take over, but with few staff was hopelessly without the capacity to handle both activities and also continue with the support of an ongoing Militia requirement. The ANMEF mounting as passed to the ADS&T 2nd Military District Lt Gibbs, another British Army loan officer, who was similary angling for inclusion in the AIF.

UK movement support

Sea Transport Service

Rail

Railhead, RSD

Postal

MFO

Repatriation

Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO PC 1870-1952

A farm worker and carpenter, Pearce joined the Labor movement, campaigned for federation and was elected to the inaugural Senate. As an anti-militarist, the defeat of Russia by Japan in 1905 converted him to espousing compulsory military training, formation of an Australian navy and establishment of military and a naval colleges.

A farm worker and carpenter, Pearce joined the Labor movement, campaigned for federation and was elected to the inaugural Senate. As an anti-militarist, the defeat of Russia by Japan in 1905 converted him to espousing compulsory military training, formation of an Australian navy and establishment of military and a naval colleges.

He was Minister for Defence from 1914 to 1921, carrying the brunt of the war effort, keeping the home defence militia active, repatriation of the AIF, and reestablishing the militia as the post-war army.

Pearce remained active politically, representing Australia at the Washington disarmament conferencs in 1921 and 1922, then taking minor portfolios until again becoming Defence Minister in 1932. He promoted an increase in expenditure as the Depression eased, mainly to the benefit of the navy. Defeated in the 1937 election, he was appointed to the Board of Business Administration, which attempted to control extravagances in the Armed Services during World War 2, and promote rationalisation between them, a topic only beginning to be tackled seriously in the present decade.

General Sir Henry George Chauvel GCMG KCB mid*********** 1865-1945

Harry Chauvel was educated at Sydney and Toowoomba Grammar Schools, then ran his father's cattle station on the Clarence River and raised the Volunteer Upper Clarence Light Horse. On moving to the Darling Downs he was commissioned in the Queensland Mounted Infantry, then transferring to the Queensland Permanent Forces as adjutant of the Moreton Regiment.

Harry Chauvel was educated at Sydney and Toowoomba Grammar Schools, then ran his father's cattle station on the Clarence River and raised the Volunteer Upper Clarence Light Horse. On moving to the Darling Downs he was commissioned in the Queensland Mounted Infantry, then transferring to the Queensland Permanent Forces as adjutant of the Moreton Regiment.

After serving with distinction in the Boer War as a major in the QMI, his return to South Africa in command of the 7th Australian Commonwealth Horse in 1902 was frustrated by the war's end. Until World War 1 he filled staff and training appointments including adjutant general and in 1914 as Australian member of the Imperial General Staff.

Transferring to the AIF in Egypt, he took part in the Gallipoli campaign, and thereafter commanded 1st Division. However when this was dispatched to France he remained commanding the Australian Mounted Division, and after successful actions clearing the Turks from Sinai he was given command of the Desert Mounted Corps. This corps successfully participated in the capture of Palestine and Syria.

Postwar he was appointed Inspector General, reporting to parliament on the condition of the army, holding this position until 1931. He also chaired the committee which recommended the structure of the reorganised Militia: this exercise was emasculated by economies which set manning levels which reduced the army from 100,000 to 40,000, with but a six day camp annually.

The force was gradually reduced and failed to mechanise in any meaningful way, keeping a horsed army at the expense of a mechanised one. He was made general in 1929, retiring shortly thereafter. The position of Inspector General was discontinued, though he reappeared as Inspector-in-Chief of the Volunteer Defence Corps in 1940.

With a considerable accumulation of transportation expertise lying fallow in the AIF in the post-Armistice period of awaiting return to Australia, a conference was called at AIF Headquarters in London in May-June 1919 to examine an appropriate postwar structure for the postwar army in Australia. While the support system in Europe and the Middle East had been substantially oriented to rail and mechanical transport, this Committee recognised that the problems of the European battlefield would he magnified by the greater distances and less developed rail, road and inland water infrastructure in Australia, and recommended that a Director General of Transportation be appointed controlling a Director of Rail Transport, Director of Mechanical Transport. and Director of Horse Transport 21. Its proposals, while recognised by the Senior Officer Committee which in 1920 met in Melbourne and reported to Minister of Defence Pearce, were downgraded on an expense basis, the preference being to keep alive the seven AIF division model, with ‘xxxxxx xxxxx to be deferred until xxxxxx’ 22. Inspector General Chauvel acknowledged the need for motor transport in his 1925 annual report but accepted that finance would not be available; water transport was not considered in any of the forums, and railways were left to a War Railway Council, the state rail systems, and the apparatus of the Engineer and Railway Staff Corps as a panacea for mobilising that resource in time of emergency 23. The transportation arm of the Army was thus left in limbo.

Responsibilities:

QMG/AG

DST&M

MFO?

Blue Book

Sea Transport Requirements Committee

Sea Transport Officers

Expedients in Tobruk and Malaya

Water Transport Service

Docks Operating

MFO Organisation

Army Transportation Corps

Postal

The Australian Army Transportation Corps was created on 6 Aug 1945 (GRO 190/1945, 20.7.1945.) to absorb the existing services of Rail and Road Transportation, Water Transport and Docks. All units of the RAE Transportation Section (Water Transport) and (Docks), the Directorates of Railway and Road Transportation, Docks, and Water Transport (Small Craft), the Water Transport Training Centre RAE, and LHQ School of Military Engineering (Water Transport), were transferred to this Corps on that date. In April 1947 it was absorbed back into the Royal Australian Engineers (Transportation).

Units:

| HQ Port Operating Groups | Small Ships Companies |

| Port Operating Companies | Port Craft Companies |

| Port Maintenance Companies | Port Landing Craft Companies |

| Landing Ship Detachments | Port Landing Craft Platoons |

| Port Operating Service Training Company | Tug and Launch Platoons |

| HQ Water Transport Groups | Landing Craft Companies |

| Landing Craft Platoons | Water Ambulance Convoys |

| Refrigeration Lighter Sections | 1st Aust Cargo Vessel Crusader. |

Japan

Army Fleet to Terminal Operations and RAE (Tn)

Tml ops

Ships staff

MC, to RACT & MCOs

References

21. AA MP367/1 631/1/132 of 11 June 1919.

22. Australian National Library MS 1827 1.1 Report on the Military Defence of Australia by a conference of Senior Officers 1920 vol II p21.

23. Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates vol 97, p11736, 12848; vol 93, p4392.