Early Australians at Arms

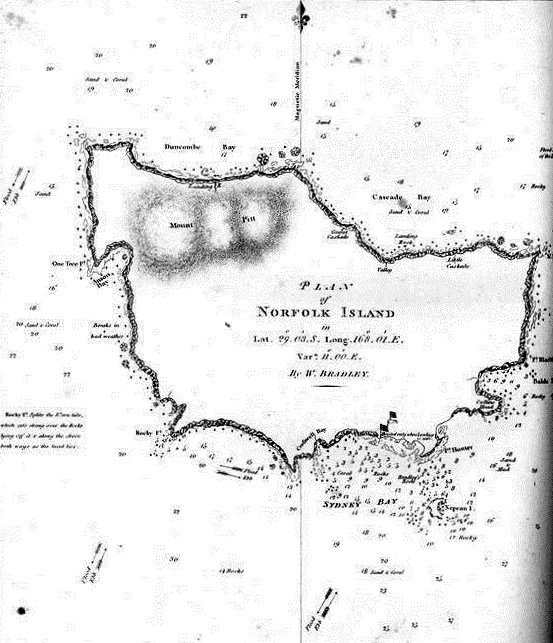

In January 1794 about half of the forty-man garrison of the New South Wales Corps at the penal station on Norfolk Island mutinied, leaving Lieutenant Governor Phillip King a severe problem of coping with protecting the settlers, stores and boats from the convicts who were stationed in several locations on the Island. His ready solution was to embody the free settlers into a militia, a not too difficult exercise as they were more than anxious to protect themselves anyway. Most were marines and sailors who had elected discharge in New South Wales, and had been given arms for self defence against convict depredation earlier by New South Wales Governor Phillip. The militia took on guard duties on roster, attended ceremonial parades and gave themselves and the other residents on the Island a feeling of security which the remaining loyal soldiers were too few to provide on a protracted basis.

King reported the mutiny to the Acting Governor in Sydney, Major Francis Grose, Phillip having left for home worn out, and his replacement Hunter still in transit to the Colony. Grose reacted angrily to the news of the embodiment of the settlers, demanding their immediate disbandment and return of their weapons to Sydney forthwith, as the latter were alleged to be needed to arm farmers on the Hawkesbury River for their self protection.

King found himself on the defensive, having to explain his action to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, but the ex-militia members demanded the right to retain the weapons given to them with Phillip’s consent. It was to no avail: they were shipped to Sydney, and the reinforced NSW detachment was restored as the sole force under arms.

Grose had been using his temporary position to replace civil authority with military judicial and administrative appointments. His reaction to the formation of a militia, even in such a demanding circumstance, reflected an ongoing characteristic of the attitude of the leadership of the New South Wales Corps to militias, and indeed that also which pervaded the rest of the regular British Army: that their existence was a slur on the ability of the Corps to do its job. A similar situation arose when King as Governor raised a small body of cavalry in 1803 in Sydney, and the existence of the Parramatta and Sydney Loyal Associations from 1803-10 was a source of ongoing simmering discontent, the senior officers of the NSW Corps using their best endeavours to render them moribund.

The progressive arrival of Irish transported for revolutionary activity introduced a strong revolutionary atmosphere into the colony of New South Wales. With his regular troops becoming more dispersed as settlement expanded, and replacements scarce due to the priority demands of the Napoleonic War, Governor John Hunter had authorised near the end of his term in 1800 a company of militia in each of Parramatta and Sydney. King accepted this but found it easy to let them lapse into disuse until receipt of news of a revival of the Napoleonic wars in 1803 caused him to resuscitate the two Associations.

Irish plotting continued, culminating on 4 March 1804 with William Johnson gathering over three hundred convicts armed with rifles, cutlasses and pikes and setting out for the Hawkesbury to double his strength and then march on to capture Parramatta and Sydney. Governor King, alerted, ordered Major George Johnston to take a detachment of the NSW Corps to suppress the rising, whereon the Corps put on a display of infantry action which belied entirely the slack and corrupt image so often attributed to them: Johnson left Sydney with a party of Quartermaster Thomas Laycock and twenty-five soldiers for Parramatta then, accompanied by the local Active Defence group, pursued the rebel band past Toongab-be to what later became known as Vinegar Hill where Johnston captured the two leaders of the of the force by a ruse with assistance from one of the Governor’s light horse bodyguard. Meanwhile the marching NSW Corps and Active Defence troops arrived, charged, dispersed and pursued the now leaderless convicts.

The intent of the rebels to capture the two towns had been betrayed by a nervous convict, so the Parramatta and Sydney Loyal Association companies turned out within the hour of the alarm being given, and took up protection of the towns, allowing the regulars and Active Defence to take up the pursuit. While the regulars acknowledged the effectiveness of the militia troops' action, the ongoing efforts of the NSW Corps hierarchy to relegate them to oblivion demonstrated that rivals under arms were not welcome.

Johnson’s coup against Bligh in 1808 was strictly NSW Corps. The Loyal Associations were not involved, indeed the possibility of their taking the governor’s side, as the petitions and increased enrollments of a year before supporting Bligh indicate may have happened, may well have added to the speed with which Johnston and Macarthur mounted the raid on Bligh’s residence. Thereafter the Associations were not heard of other than when successor Macquarie, imbued with a regular’s preference regular forces, arranged their demise.

Discovery of gold in New South Wales and Victoria was seen by conservative elements in the colonies as a great threat to law and order, with demands and pleas for more imperial troops to maintain control and to counter the possibility of privateers holding the cities to ransom for the gold held awaiting shipment. However the flood of immigrants seeking their fortune quickly became potential settlers when alluvial mining petered out.

On the goldfields of Victoria it became necessary to sink shafts to buried river beds to seek alluvial deposits, and survival during this tedious and often fruitless search made payment of £1 a month beyond the reach of the less fortunate. However licence searches were carried out with vigour and violence by the goldfields police, with digger hunts after those anxious to avoid inspection a regular occurrence.

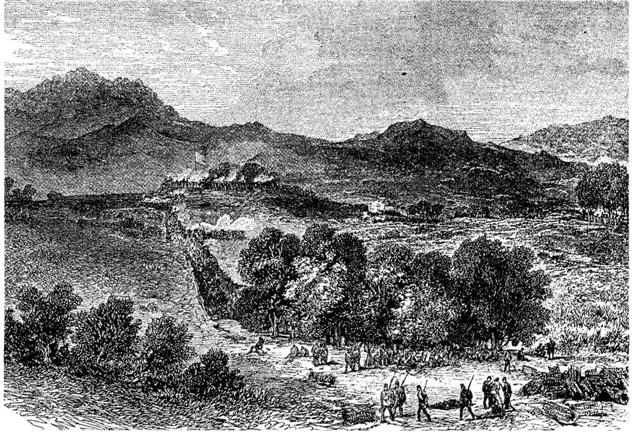

This plus a perception of miscarriage of justice persuaded the miners at Ballaarat to form an association to protest to newly arrived Lieutenant Governor Hotham, who set aside their demands and, encouraged by conservative forces in his unelected government, to make an example for law and order. The miners, alarmed by the warlike preparations in the siege-minded government camp at Ballaarat, raised a militia of about 1,500 and raised a stockade to protect their training ground from incursions from mounted police still conducting digger hunts.

The troops in the government camp were progressively reinforced to about 600 and Major General Nickle, who had recently relocated his Australian Command headquarters from Sydney to Melbourne to solve his personal housing problems, set out for the camp with a similar number.

A miners’ delegation on the evening of 2 December 1854, complaining about yet another provocative digger hunt, this time using troops as a backup, was told by goldfields Commissioner Rede that they were really plotting to form a democracy, an indeed serious accusation in that era. Early the following morning, with most of the miners’ militia gone home for Sunday leaving about 120 in the stockade, a force of 182 soldiers and 94 police made a night march to the stockade and assaulted it at dawn, with a few battle casualties on both sides during the fight, and some murders of the defeated and bystanders by the mounted police afterwards.

Thirteen suspected ringleaders were taken to Pentridge gaol which was fortifid against possible attack. But despite most strenuous efforts by the Attorney-General, the treason trial jury found them not guilty. Meanwhile a commission of enquiry set up after the uproar in Melbourne over the attack supported the miners’ against the impossible licence impost and for their enfranchisement. Ballaarat Reform League leader Peter Lalor, who was wounded in the attack but escaped, was elected to the new democratically elected parliament and later became its Speaker.

This self-defence attempt to end being ridden down, sabered and shot at like animals during licence hunts has often been condemned even in recent times as an attempt at revolution, but by the same type of conservatives as those who forced the problem to flash point in 1854. Contemporary public opinion in the Colony was strongly against the government action, the commission recommended that the miners demands be met, and their leaders were acquitted and elected to parliament.

As Lalor said in his first election speech to justify the stand made at Ballaarat: what alternative did free men have to government sponsored violence and rejection of petitions seeking relief – King John had given Magna Carta to barons with arms in their hands, not a petition.

Those Maori chiefs who signed the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 imagined that they were taking on imperial protection of their lands and rights, rather than the exploitation which followed. From 1844 intermittent warfare erupted, with increasing numbers of imperial troops from Australia and England used to control uprisings. Peace was restored in 1847, but the same troubles of land piracy culminated in a new outbreak in Taranaki in 1860-1 during which Victorian Colonial Navy steam corvette Victoria provided support to the imperial troops.

To the north in the Waikato Valley a further outbreak of trouble brought on a full scale war in 1863, for which the New Zealand Colonial Government, finding reluctance amongst its own inhabitants to join the local forces, sought to raise substantial militia forces in Australia on the promise of farms in the Waikato for those who completed their three year engagements. Rallying to the twin incentives of the call of Queen and Country, and the promise of farms on rich land difficult to come by in the squatter- controlled Australian colonies, some 1,784 men enrolled in the Waikato Regiment, sometimes referred to as the Waikato Militia, together with 31 Australians who joined the Regiment in New Zealand from the Otago goldfields. Another 553 enrolled in the Taranaki Military Settlers for service in the Taranaki district on the south west of the North Island.

The former were embodied in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Battalions of the Waikato Regiment, used initially mostly on protective duties, as the lines of communication absorbed about 40 percent of the total force deployed in the Waikato campaign. After being involved in the Waikato campaign and the following one around Tauranga in the east, they were quickly settled at Alexandria, Cambridge and Hamilton in the valley, and at Tauranga to the east, so placing the military settlers on free seized land in a defensive circle coincidentally protecting the settled areas during the ensuing eight years of guerrilla warfare, and also coincidentally saving the Colonial Government the expense of paying them.

This loss of pay left the militiaman, who were given free rations for the first year only, without the resources to pay for development of their farms, and disillusioned, many sold up as soon as they had finished their engagements. Those who wished to remain on the rolls transferred to the 4th Battalion Auckland Militia.

A more durable group was formed in the Commissariat service. Volunteers were accepted from regulars and militiamen, and about 300 Australians served in the Commissariat Department and Commissariat Transport Corps of water and land transport. As these troops were required to support the ongoing actions over the following years in the east and south, they remained on active duty and so could afford to develop their farms and became the most successful settlers. They were also awarded the majority of New Zealand Medals to Australians as these were awarded to those who had been present at the various battles of the war.

Descendants of Waikato Regiment Australians still live in New Zealand, occupying some of the richest farming land in the country.

To be entered.

More formal colonial forces were engaged in subsequent colonial wars in support of the Britain's imperial engagements: the Soudan 1885, the Boxer Rebellion 1900 and the Second Boer War 1899-1902, which latter involved not only colonial contingents but also te first of the Commonwealth of Australia ones to serve overseas. However these early ones should not be brushed over – they are the beginnings of Australia's military history and exemplify, more than overseas imperial ventures, the beginnings of our national and Anzac military traditions.

Historical Reconds of Australia

Historical Records of New South Wales

Lindsay N. Equal to the Task vol 1 The RAASC Kenmore 1992

Molony J. Eureka Penguin 1984

Silver L.R. The Battle of Vinegar Hill Moorebank 1989