Chapter 14

Graduates Progress

Members attending the earlier courses at Portsea were informed quite matter of factly that their career as an officer was limited to the level of major. This was not so fearful a sentence as it might appear to those conditioned to the expansion and growing career structure of the Vietnam War era, or the rank explosion associated with that of the Defence bureaucracy in the 1970s. Until the 1960s, with promotion above the rank of major severely restricted by a tight rank pyramid, most RMC graduates also had limited horizons, with many facing the prospect of a cut off at major and the associated retirement at age 47. As it turned out, the initial concept of OCS graduates as fill-ins to make good a deficiency of junior and middle level officers, and to replace the wasting carryover World War 2 and short service commission group, was overtaken by the growing commitment to maintain forces overseas. In particular the demands of the Vietnam War, where the system of rotating all ranks for a year followed by at least two years before return to the theatre was permitted, maintained an ongoing demand for large numbers of officers to operate the units in preparatory training as well as the training and administration system in Australia. But while RMC continued its enlarged output, and the short-course Officer Training Unit at Scheyville turned out others for limited or special service, the greatest input was from Portsea, as demonstrated in Table 17. It is apparent from these figures that Portsea provided the backbone of the Regular officer corps for over four decades.

Successful officer cadets were commissioned as second lieutenants except that those with university degrees graduated as lieutenant. The rank of second lieutenant had been suspended in 1942, though vestiges remained in the Citizen Military Forces in the longstanding lieutenant on probation, and in the School Cadets as cadet officer, both appointments wearing the one star insignia as opposed to two stars for a lieutenant, though the latter was changed to under officer with OCS's arrival on the scene. The decision to commission officers after a six month course at Portsea brought problems of equity vis a vis Duntroon graduates who had to complete a four year course before commissioning as a lieutenant. Apart from the levels of qualification and training there was the obvious problem under the automatic promotion system of two men entering OCS and RMC simultaneously, and graduating three and a half years apart: why would anyone consent to go through the RMC stream, which did not even produce a degree, and end up watching their OCS contemporaries becoming captains shortly after they themselves had made lieutenant? The solution arrived at was to re-establish the rank of second lieutenant and decree that OCS graduates should spend four years in that rank, the total including the six-month course and so over-matching the four year incarceration at the other place. And as a little salt in the wound, graduates in RMC classes were given seniority over OCS courses graduating in the same period, regardless of the actual commissioning date 1.

While there was a strong element of necessity in such a system, there arose a succession of anomalies and changes in relativities. Firstly some RMC cadets unable to continue on at Duntroon by either academic failure or marriage were offered entry to OCS if considered likely to make efficient officers. These would already have consumed part of the differential time in the rank of second lieutenant, which had also been reduced to three and a half years; then in 1955 the OCS course was extended to a year, while direct commissioning as lieutenants into RAE, RAEME and to a lesser extent other corps was further eroding the rationale for the extended promotion lag. The residual argument was that of education levels, which could not be compromised. University undergraduates were given credit for their study time, up to being commissioned as lieutenants, depending on the length or of achievement of qualifications. Then, as a result of the 1979 Regular Officer Development Committee recommendation that the rank of second lieutenant be eliminated, the period of graduates in that rank was progressively reduced to six months, so that the new eighteen month course at RMC in 1986 would finally shade out the combined period of the OCS course plus that six months.

Another hurdle was faced by most of the early graduates. An intermediate education standard was accepted for entry as a means of getting entrants from both within and without the army in the desired numbers from a community where that level of education was still the norm for entry into the public service, banks and large corporations. But there was a policy double-think which, while accepting that the School was there to provide regimental officers in numbers and not compete with RMC, still required OCS graduates, as members of the Staff Corps, to somehow meet the same standards of civil and military knowledge as those of the RMC entrants. The solution to this paradigm was to require second lieutenants to reach Leaving standard as a pre-requisite to promotion to lieutenant. And while the three and a half years after commissioning might seem to provide an adequate period to achieve this, the reality of life as a junior officer was firstly doing the military post-graduate courses, then usually a posting to a training unit, remote from education facilities and working extended hours and weekends. The time and energy necessary to complete part time subjects which took high school students two years full time study was simply not there, and even though commanding officers were exhorted to make opportunities available to facilitate such qualification, they normally required the full pound of flesh from all their junior officers regardless of liabilities for promotion examinations, military or civil. Those earlier graduates who already had the requisite level on entry to Portsea were to consider themselves fortunate in their early commissioned lives: this remained so until 1968 when the entry level was set at leaving, except for service entrants, but these latter could now earn credits from the academic side of the OCS course to qualify for the necessary four SGCE subjects which were then accepted as meeting the promotion requirement 2. Over two thirds achieved this, and so the problem fell back onto a few laggards, whose problems were of their own making.

Subsequent to their promotion to lieutenant by whatever means, the time spent in each rank was something of a moveable feast, influenced by a variety of factors. From the formation of the Australian Regular Army in 1947, officers who were qualified and recommended were granted substantive promotion automatically after four years as a lieutenant and six as a major, thereafter promotion being by merit selection against vacancies. This automatic timed system progressively created problems as rank creep in the Regular Army created an imbalance in officers at each rank, with increasing demands for non-existent experienced middle level officers who had been absorbed into the next rank on temporary promotion. The 1960s saw a prostitution of the ranks of captain and major, just as the 1970s saw the same for the senior ranks. The increase of captain and major positions created from 1960 onwards fed on itself, expanding the demand for officers of those ranks, which accelerated earlier and earlier temporary promotions to fill them, which in turn diluted the experience and performance ability at lieutenant, captain and major, so creating desires to further lift rank levels to get more capable occupants, which in turn stretched and diluted the available experience levels further, and so the cycle went on.

In a closed shop with little potential for lateral recruitment and a steady wastage rate, the remedy lay in introducing more officers at the bottom of the pyramid and waiting for them to progress slowly up it. This was a happy enough situation for those on their way up, many becoming temporary captains shortly after attaining lieutenant, and temporary majors three years after substantive captain. Some unusual cases did even better: J.O. Furner in an officer-starved Intelligence Corps became a temporary captain six months after lieutenancy, and a temporary major nine months after substantive captaincy. Some corps had been allowed to so over-establish themselves that they had virtually eliminated the rank of lieutenant: RAE, RA Sigs and RAASC troops and platoons were commanded by captains, leaving new officers without their birthright – a command – and shuffled into some basic administrative post or extended postgraduate schooling to occupy them until they could be promoted to captain in an over-ranked position which gave the trappings and remuneration but not necessarily job satisfaction or practical experience. It was in the latter aspect, however that Portsea graduates shone: the period spent as a second lieutenant had allowed acquisition of a basic grasp of practical soldiering so that accelerated promotion later did not leave them as inexperienced captains, as it did many of those who had been commissioned as lieutenants.

Sir Arthur Harold Tange AC CBE1914-2001

Joining the public service as research assistant in Department of External Affairs in 1954, he rose rapidly to Secretary of the Department, then in 1965 moved to High Commissioner to India.

Joining the public service as research assistant in Department of External Affairs in 1954, he rose rapidly to Secretary of the Department, then in 1965 moved to High Commissioner to India.

Returning in 1970 as Secretary for Defence, he set on a path of amalgamating the separate Departments of Army, Navy and Air Force into it, creating an immense bureaucracy not answerable to the Defence Force command system. This amalgamation was in place in 1975 when he is on record as stating that he 'created the super-department to facilitate efficient administration of Defence'. In this there was no mention of the fact that the function of Defence is Defence, not administration.

While there was a compelling need to push the divergent Services onto a common path of joint operation, his chosen path of a vastly overblown civil and military bureaucracy, cemented and expanded by his successors – civilian and military – consumes a large part of Defence funding, and also presides over spectacular failures in major equipment projects.

By February 1967 the number of serving OCS graduates had outnumbered those of RMC 824 to 818, though at this stage the measured cursus honorum which masqueraded as a career path in the army had not allowed any of the former past the rank of major. However times were changing. From a lean pre-Vietnam army hierarchy of 19 brigadiers and 40 colonels, it was expanded to 30 and 68 to match the doubled army by 1971; then, even in the face of a shrinking force structure, the functional command and Tange restructurings generated a continuing escalation to 46 and over 100 respectively by 1977 3. Without the ability of the public service and commerce to recruit laterally, the available talent had to fill space, resulting in many officers from all sources, who were previously without real prospects of promotion, benefiting from another bonanza at senior ranks similar to the one they had met in the middle levels a decade before. Unfortunately once again the substance of many of the new creations, especially in the Defence Central arena, did not meet the expectations which the rank level should have promised. It is only in the so-called cuts of recent years that some value has been put back to many of these positions.

Portsea graduates were fortunate in the sense of following the crest of this expansive outlook to which there were few setbacks until about the time of the merger with RMC. The Job's comforters who had made the early predictions of limited career opportunities were confounded by the demands of an expanding army hungry to use the available talent, and OCS graduates were able to provide this in quantity and quality, resulting in their being well represented in the promotions at each rank. In 1969 J.O. Furner was the first to lieutenant colonel, in 1976 L.A. Wright to colonel, 1978 Furner to brigadier, and 1991 D.J. Mclachlan to major general, with F.J. Hickling the second a year later.

At the silver jubilee parade in June 1977 commandant P.G. Cole was able to advise that Australian graduates then numbered five colonels and 139 lieutenant colonels in their ranks, with six lieutenant colonels in New Zealand and eight in Malaysia, two colonels and one lieutenant colonel in Singapore, and in Papua New Guinea one brigadier general, three colonels and eight lieutenant colonels. In 1995 serving Portsea graduates in Australia included one major general, six brigadiers, 35 colonels and 139 lieutenant colonels; New Zealand two brigadiers, four colonels, 34 lieutenant colonels, the latter two thirds of the total; Papua New Guinea unchanged, Fiji one brigadier general, one colonel, five lieutenant colonels; Malaysia two brigadier generals, seven colonels, 18 lieutenant colonels; Philippines one major general, three brigadier generals, four colonels, two lieutenant colonels; Brunei one brigadier general, one colonel, six lieutenant colonels; and Singapore three lieutenant colonels 4.

On graduation, the new officers became members of the Australian Staff Corps which since 1911 had been the sole means of gaining a permanent commission in the Australian Army, other than for some proscribed technical corps whose members were limited to employment and promotion within those corps. Originally RMC was to be the sole avenue of entry but from the beginning necessity ensured an array of exceptions to this, using such devices as continuing pre-war commissions after World War 1 and the RMC Wing courses after World War 2; then, in a less doctrinaire era, biting the bullet and amending the Defence Act to formalise all officer courses – OCS, WRAAC OCS, OUT and Officer Qualifying. Post World War 2 Staff Corps graduates were immediately allotted as a matter of practicality to a functional corps, in which area they specialised and found most of their regimental service, and which was responsible for their general career management, except that officers who reached the rank of colonel lost that overt corps affiliation; the office of the Military Secretary oversaw those facets relating to general postings and career qualifications as well as all those of senior officers. Table 18 shows the allocation to corps for each year, reflecting the army's changing needs for various professional disciplines.

OCS originally produced officers for the main combatant corps which comprised the Staff Corps – RAAC, RAA, RAE, RA Sigs, RA Inf and RAASC in keeping with the purpose for which it was established. This was soon of necessity extended by including the proscribed corps of RAAOC and RAEME, however after the initial demand for all these corps had been satisfied, it became expedient to train officers in other specialist areas. Progressively a trickle of Survey, Aviation, Intelligence, Medical, Catering, Education, Psychology, Band and Military Police graduates entered commissioned service, properly trained to a basic professional standard appropriate to career Regular officers. Whether surveyors, education officers, psychologists and bandmasters required a year of officer training to perform their task adequately might well be open to question. It could be argued that having a percentage of officers of such corps with a full military professional background would facilitate their performance and credibility in corps staff appointments and as directors of their corps, but of course there was no guarantee whatsoever that these would be the ones to end up in those positions. And there was no suggestion that medical, dental and nursing officers should do the year at Portsea, even though the argument might apply at least as strongly to them as to the other peripheral corps. However, the mainstream lay in the major combatant corps and, after completion of their corps post-graduate training they were posted to their first unit as a commissioned officer.

The Army of the 1950s was a training army. Apart from an undermanned regular brigade group not given real life until 1957, the regular component was absorbed in training and administering the National Service basic training units and the CMF units which absorbed their output, reverting largely to the Permanent army functions which had existed since Federation other than during the two World Wars. A most obvious outcome of this was that all newly commissioned officers started their careers as a regimental officer in a recruit training unit – either the regular recruit training battalion at Kapooka, or more likely one of the ten National Service training battalions located near each State capital, which conducted the three month full-time recruit training of the universal National Service inductees. While not greatly desired postings, they offered newly commissioned officers from all sources an invaluable grounding in the basic trade of training, management and administration of soldiers which would stand them in good stead for the remainder of their service.

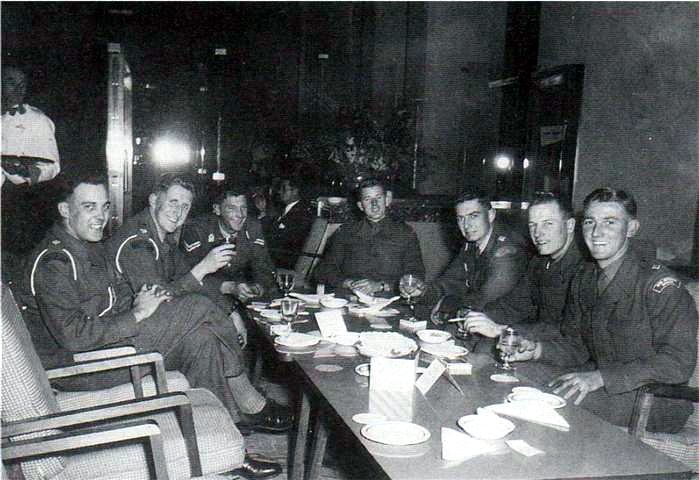

After an often extended period there, a young officer could look forward to joining a regular regiment, squadron or company depending on corps. This often meant service overseas, some with the British Commonwealth Force Korea, though few Portsea graduates made it before cessation of hostilities in 1953. Then commitment of a battalion group to anti-terrorist operations in Malaya in 1955 expanded opportunities for overseas service, with an alternative of service with the Pacific Islands Regiment in Papua New Guinea, at that stage a unit of the Australian Army with Australian officers. A combination of these recruit training and regimental postings gave the OCS graduates a depth of regimental experience which, leavened by the plethora of responsibilities as duty officer and extra-regimental duties in stocktaking and checking, regimental audit, courts martial, unit recreational activities and soldiers' welfare, made them such a valuable asset that many commanding officers expressed preference for Portsea officers over their Duntroon contemporaries who had yet to get this practical background.

An almost certain follow up to early regimental duties were postings as adjutant of a CMF unit and a grade three staff posting on the general, personnel or logistics staff at a command or area headquarters. This combination of recruit training, CMF and staff postings, while not necessarily the first choice of a young officer, was accepted as a matter of course as it was an essential element of a full career: they were for two decades one of the pre-requisites, together with written and practical examinations, for entry to the Australian Staff College or overseas equivalent, or the Royal Military College of Science in the United Kingdom, qualification at one of which was a virtual necessity for eventual promotion beyond major. Other postings such as instructor at an army school or overseas might be welcome but not essential. An officer who had commanded at each rank level, filled a grade three and grade two staff position and passed a staff college, had no obstacle other than indifferent performance in gaining selection for promotion to lieutenant colonel. For selection beyond that, attendance at higher colleges combined with satisfactory command and staff experience provided a similar effective combination.

As the course at Portsea was designed to give a basic military education applicable to all arms of the service, and indeed was limited to that scope by its duration, it was necessary for newly commissioned officers to be given some element of specialist training in their allotted corps. This was effected at the appropriate corps schools, which had a variety of approaches to the problem, ranging through a special course for infantry graduates, an artillery introductory young officers course also accommodating RMC graduates, armoured crew commanders courses, with RAASC simply using a standard all arms vehicle officer and NCO course. While there was a shortage of officers this economy mode remained, but as the basic deficiencies were overcome, broader post graduate courses evolved in some corps. While rational corps such as Armour, Artillery and Infantry retained a series of progressive short courses scheduled at different phases in an officer's career according to need, RAASC initiated a six month course covering all areas of corps activity regardless of immediate employment prospects, and RAE in 1962 capped all with a two year course for those without engineering degrees which condemned its junior officers to an extended purgatory. Even those undergoing short courses tended to resent the post-graduate courses, for newly commissioned officers wanted to get on with what they had been trained for, and their treatment at the corps schools was all too often one of harassment, which provoked a reaction against what was a virtual continuation of their officer cadet experiences, and that in turn led to a cycle of further repression and reaction. And while the short junior officer courses might at least confine such bastardry to a few weeks, the later extended courses provided an unnecessarily bitter introduction to life as a regular officer.

In keeping with the Staff Corps tradition, the key to an extended career in the Regular Army was qualification at Staff College. Entry to these courses was achieved by selection from those qualified at the tactics course required for promotion to major under s.21a of the Defence Act and also at the pre-entrance examination, originally a formidable barrier in the form of six subjects all to be passed at the same attempt, with a maximum of three attempts; from 1963 this was progressively watered down so that it became a nuisance rather than a barrier, and was finally abolished. OCS graduates began to attend the Staff College at Queenscliff from 1963-64 when H.L. Bell broke the ice, followed by a regular stream in succeeding courses. The parallel courses in overseas staff colleges at which Australian officers were offered places also attracted their share of OCS men: N.C. Munro was first to attend the Royal Military College of Science in 1960-62, L.A. Wright the Staff College Wellington in 1966-67 and J.O. Furner the Command and General Staff College at Leavenworth in 1962-63. Two years after the Joint Service Staff College opened in 1970 graduates began attending with L.A. Wright leading the way 5.

Attendance at courses of other armies was a standard component of training the Australian officer corps, following a practice inherited from the colonial forces, aimed at variously developing a breadth of military understanding, acquiring technical expertise and keeping up with new developments in operations and equipment. As well as the staff colleges, courses at British and American Army schools were used for a wide range of specialist officer training, and exchange postings had a similar basis of exposing officers to different perspectives of operations. As Portsea graduates grew in numbers and seniority they claimed their share of exposure to this overseas training. In addition to this, others demonstrated that OCS entrants were not necessarily those unable to make the academic grade and gained tertiary qualifications at a variety of universities, both while in the army and after they left. While RMC students transferred to Portsea after academic difficulties, OCS graduate D.N. Thornton seems to have been the first to reverse the process and gain a degree from RMC's University of New South Wales college. Some graduates attended universities and institutes of technology to gain civil qualifications which were of use to the army as sponsored full time or part time students, while the dedicated took courses of their choice part time under their own volition. Although these were mainly from the technical corps, with a high proportion of ex-Army apprentice graduates, others qualified in the arts and commercial fields, with some such as I.W. Coombe, O.M. Eather and R.L. Bricknell going on to higher degrees 6.

The United Nations force assisting the Republic of Korea against invasion by North Korea and China had been in being for nearly two years by the time of the first graduation from Portsea. Although G.E. Ball and R.W. Strong MM arrived at OCS as veterans of Korea, and R.G. Lange was advised to go to Portsea as the best way to get there, J.F. Williams was the only graduate to get to the action in early 1952 through the back door, attached to a British armoured unit. Of the others H.L. Bell, D.M. Bourne, J.B. Colquhoun, J.O. Furner, P.F. Kent, N.E.W. Granter, A.R. Roberts and H.J. Spalding were held back on the basis that the many ex-World War 2 veterans of K Force were unused to the idea of second lieutenants, arriving a year after the armistice. In parallel an ongoing succession of infantry graduates, starting with R.G. Lange and T.H.R. Jackson, were diverted to Papua New Guinea, where an officer-starved Pacific Islands Regiment was desperate for platoon commanders; many of these graduates returned later in their service as company and battalion commanders. The hazards of service in Papua New Guinea have only recently been recognised retrospectively with award of the Australian Service Medal.

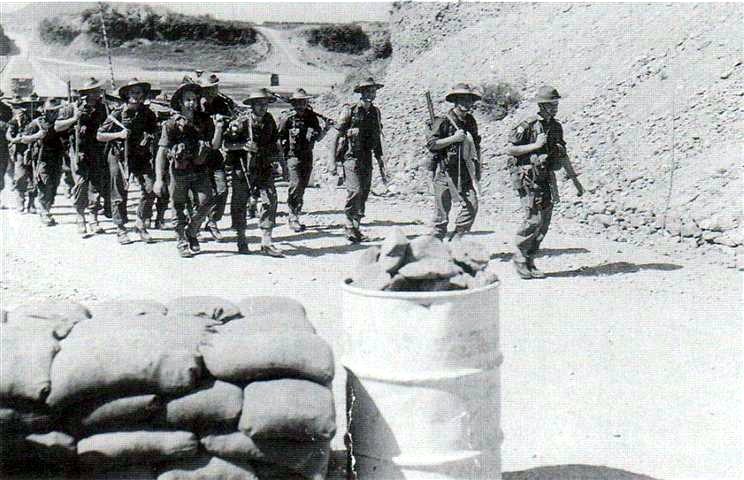

Australia's participation in efforts to suppress the communist terrorist activity in Malaya was initiated with deployment of No 86 Wing RAAF in 1950, but the political approach to army employment was conditioned firstly by a commitment to a potential rerun of the Western Desert World War 2 style, which was overtaken by absorption of army effort in maintaining two battalions in Korea. Termination of that war brought a reversion to the Middle East concept, until a political decision in 1955 to commit a battalion group to the British Commonwealth Strategic Reserve in Malaya. Successive battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment, an artillery battery plus a range of staff postings in 28 (Comwel) Bde, Australian Army Force Singapore, Far East Land Force Headquarters and its support units, and a Visitors and Observers Unit, all provided a wide range of opportunities for OCS graduates to participate in, and contribute to, the long-running campaign to ensure that the embryonic Federation of Malaya was not taken over by a totalitarian regime. In all over 40 graduates are recorded as having participated in this theatre, though at this stage up to the end of the emergency in 1960 they were all still junior officers.

Further operations were conducted against the terrorists on the Malay-Thai border in the 1960s, the battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment participating. Although not recognised for the purposes of award of the then-current general service medal, it has now been declared as qualifying for the Australian Service Medal in a belated acceptance that the colonial-mentality of accepting British dictums on national matters was much overdone. A more serious conflict arose from adventurism by Indonesia's President Sukarno in his support of the Brunei revolt in December 1962, followed by his declaration to demolish the newly formed state of Malaysia the following year, drew in Australian troops from the Commonwealth Strategic Reserve. These were committed to helping put down the Brunei insurrection, repelling raids made on the Malay Peninsula and then were involved in the extended border protection operations in Sarawak and later in civil engineer work in Sabah. It was in Malaya in 1964 that the first fatality on operations of a graduate occurred – Lt D.J. Brian was accidentally shot searching a cave. These operations continued for a decade, with 43 graduates recorded on war service in Borneo, 24 in the Malay Peninsula 7.

Australia's initial commitment in South Vietnam was the Australian Army Training Team of 30 commissioned, warrant and non commissioned officers to assist in stiffening an Army of the Republic of Vietnam hurriedly expanded as Viet Cong insurgency increased with the support of North Vietnam. The Team was doubled then eventually expanded to 100, its members employed in advisory and command appointments with the South Vietnamese army, local and irregular forces throughout the country; the OCS graduates in its ranks shared in the enviable reputation it built up, with Maj P.J. Badcoe winning a posthumous VC. This assistance was expanded to a battalion group in 1965 as part of the Free World buildup in response to the commitment of North Vietnamese regular army formations into South Vietnam, then in 1966 it was increased to a brigade-sized task force based at Nui Dat in Phuoc Tuy Province, a Logistic Support Group at the port of Vung Tau and Force Headquarters in Saigon. From thereon OCS officers filled their normal proportion of postings in all these units as well as in AATTV, the majority having at least one tour in the theatre, some two or three 8; air force ground defence and administrative graduates also participated with the RAAF component of the force. By this stage many of the graduates had reached the rank of major and were commanding companies or filling senior staff postings on the force, task force and logistic support force headquarters. The operational awards in Table 20 indicate the increasing prominence and effectiveness of Portsea graduates within the army.

Video: A Graduate goes to War

The Australian Army was at something of a loose end after the withdrawal from Vietnam in 1972 and the following year from ANZUK Force in Singapore, to face a role of continental defence. With no wars to fight, it reverted to a training army and, for the first time with a standing operational force of three brigades, looked for operational experience. United Nations peacekeeping tasks came up progressively, but herein lay a problem: infantry battalions were available from any country, but logistics expertise was rare and Australia was one of the few countries acceptable in UN forces which was regarded as sufficiently sophisticated in this field. Canada had long provided this but was tiring of the ongoing commitments which distorted its own operational structure. In consequence UN requests for Australian participation centred on this area, but the then army hierarchy wanted to find employment for infantry, and advised the prime minister of its inability to provide logistics units, so major opportunities passed over.

Some early UN observer missions had drawn on Australian support but it had been a longstanding practice of the permanent army since federation to avoid extraneous duties, leaving British officers to fill ADC positions for vice-royalty and similarly, when it came to providing observers for UN missions, the Regular Army left it to others. The first was the long-standing UNMOGIP observing the Kashmir cease-fire line, from 1952 the six observers being found from CMF officers on full time duty as was largely the case from 1956 with the four or five observers for UNTSO on the Arab- Israeli border. This remained until the post-Vietnam hiatus provided the incentive for the Regular Army to participate as a means of finding productive overseas employment with an operational flavour, particularly with governments now anxious for Australia to be a good world citizen. After filling the hitherto ignored positions on UNMOGIP and UTNTSO which have continued on to the present, an opportunity presented itself in 1979 with the Commonwealth Monitoring Force to implement the transition from Southern Rhodesia to Zimbabwe; for three months an Australian Army team monitored the disarmament process and borders; 19 graduates participated 9.

A second non-UN force, raised under US sponsorship as the Multinational Force and Observers to supervise Israel's return of the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt, from 1982- 1986 then from 1993 onwards, included six graduates. Then, following the 1988 truce between Iran and Iraq, UNIIMOG was established and remained until withdrawn on the eve of the Gulf War in 1990. This deployment was followed closely by culmination of a longstanding commitment to provide a contingent to UNTAG for the transition to independence in Namibia, realised in 1989-90 when an engineer group was dispatched to support the UN Force, nine graduates participating in two contingents. Then, with a United Nations flexing its muscles in the post-Soviet breakup, further contingents served in the Gulf War 1990-91 (seven graduates), Habitat the Kurdish relief operation in Northern Iraq 1991 (two), UNMCTT the mine clearance training team in Afghanistan 1989-92 (12), MINURSO the Western Sahara referendum 1992 (two), UNTAC the Cambodian settlement 1992-93 (17), UNITAF/UNOSOM II the Somalia relief battalion group 1993-94 (nine), ONUMOZ the Mozambique settlement 1994 (one), and UNAMIR the relief expedition in Rwanda 1994-95 (16) 10.

Overseas graduates have participated in internal counterinsurgency operations, United Nations missions and in the wider conflicts. New Zealand was involved in Malaya, Malaysia and Vietnam; Malaya-Malaysia was obviously involved in the terrorist and confrontation emergencies, R.M. Chandran being awarded a posthumous SP, equivalent to the VC, in 1971; similarly Thailand had its own insurgency to contain, and the sole OCS graduate Surajit Shinawatra was killed on the Thai-Laos border in 1973; the Philippines has also had longstanding insurgency and separatist problems, with four graduates lost on operations. The Vietnam war involved, as well as the Anzac graduates, those of South Vietnam and Cambodia who have disappeared from sight. Also involved in a civil war were the four from Nigeria, two being on the Biafran side.

Papua New Guinea faced potentially dangerous border problems with Indonesia in 1988-89 which fortunately did not come to open hostilities, but has later had to deal with serious problems in the Bougainville secession movement with, on the government side, an army commanded by Portsea graduates, and on the other side the Bougainville Revolutionary Army commanded by graduate S.M. Kauona. An excursus into international peacekeeping was undertaken in 1980 in suppression of the post-independence secessionist movement in Vanuatu, a PNG force commanded by R. Diro and A.R. Huai airlifted in by the RAAF providing a quick and effective cleanup of the problem. But one of the most operationally active groups has been the graduates of Fiji. They participated in the Commonwealth Monitoring Group in Rhodesia-Zimbabwe and continue in the Multinational Force and Observers in Sinai, but their main effort has been in a longstanding contribution to the UN force in Lebanon. Fiji has provided a battalion to UNIFIL from 1978 to the present, and OCS graduates have distinguished themselves as unit commanders and on the force headquarters, Brig Gen J.K. Konrote being deputy force commander in 1990-91 11.

While graduate Lt D.J. Brian had been a fatal casualty in Malaya in March 1964, this was an isolated loss so it was not until Capt G.R. Belleville was killed in action while serving with AATTV in 1966, with an increasing number of graduates being committed to an ongoing conflict, that the need for a substantial memorial at the School began to appear necessary. Succeeding casualties over the next year gave impetus to the idea and Mr E.R. Barrett of the Master General of the Ordnance Branch in Melbourne undertook design with most of the costs of construction met by the OCS staff and cadets, with some Melbourne companies and local residents and businesses of the Mornington Peninsula donating materials and labour.

The memorial was sited between Badcoe Hall, named after the Victoria Cross winner, and the cadet accommodation buildings so as to always be in prominent view of the students, and a reminder of both the fallen of their predecessors at the School and the dedicated nature of their chosen profession. As it also abutted the parade ground with the flagstaff flying the OCS flag at its rear, it was also a backdrop to ceremonial parades. It was unveiled on 3 December 1967, and remains in place after the handover of Portsea to the School of Army Health 12. A memorial plaque mirroring the names on the memorial has been established at Duntroon on the terrace above the parade ground alongside those of the Corps of Staff Cadets.

[afternote: The memorial has been relocated to Duntroon]

In an earlier generation it was customary to wish graduating regular officers ‘bloody wars and quick promotion', an acceptance of the inevitable outcome of war, but an unfortunate commentary on complacent attitudes to conflict. But it has been a universal blessing that the containment wars of the 1950s and 1960s, successfully aimed at holding the line against the expansionist totalitarian powers, were to Australia far less bloody than their predecessors. As a result, losses of OCS graduates were mercifully few compared with the magnitude of the eventual success and vindication of the actions in forestalling the takeover of much of the world, until the expansionist regimes collapsed under their own contradictions, inefficiency and internal revulsion against their brutality. Nonetheless the casualties were relatively significant in an era where the 'bloody wars' approach has been replaced by a professional Army perhaps more cautious about foreign entanglements than many politicians, and certainly than the jingoistic warriors left over from yesteryear. And the even greater national blessings of two decades of peace followed by the collapse, at least for the present, of the totalitarian powers which originated those proxy wars has seen the cessation of those casualties. However commitment of the Australian armed forces to Korea, Malaya, Malaysia and Vietnam has been replaced by support of ongoing United Nations humanitarian peacekeeping efforts aimed at curtailing and preventing hostilities in a continuing and sad saga of human conflict around the globe, where the dangers remain in the often thankless task of keeping opposing forces apart. The casualty list of the Company of Officer Cadets is contained in the accompanying Roll of Honour: in the words of the inscription on the Memorial:

May it remind all who pass this way

of those who served their country, even unto death

During and after their service many graduates experienced diversions from the usual run of operational and administrative endeavour, such as I.C. Teague who was expedition leader for the ANARE at Mawson in 1976-77, a succession of graduates starting with W.S. Bathurst and L.P. Tonagh commanding the DUKW detachments which supported the annual ANARE reliefs, and R. Clark who took mercenary service with the Sultan of Oman forces in 1977. While the majority of graduates remained to experience a full career in the regular army, many left for various reasons and turned their skills to other areas. For those coming to the end of their service and not wishing to leave a specific area for family or other reasons, the public service or defence support industries were an obvious avenue, especially for those well settled in Canberra. Others had a different path away: P.C. Jones, allotted to run the Governor General's household after the official secretary declined to continue this responsibility, then moved on to secretary of Brisbane Tattersall’s Club. A common route was in further education where members undertook part time studies which either qualified them to move into the public or private community or stimulated their interest in other areas.

Some continued their service after leaving in the CMF and Reserves, like P.P. Smith who went through a tangent as OC 1 Mob Malaria Control Unit before ending as commander of 7th Brigade. Others ventured into politics: RAAF graduate Gp Capt R.G. Halvorsen became federal MP for Casey and is currently Opposition Chief Whip; Lt Col D.G. Burke finished in northern Australia commanding 2nd Cavalry Regiment and then moved on to become the Minister for Power and Water in the Northern Territory government; and Brig-Gen R. Diro, after commanding the PNG Defence Force, became Deputy Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea.

In the commercial world they have moved on to a range of ventures of varying scale and scope according to their background, talents and interests: RAEME graduate F.R. Maloney is proprietor of a string of Matilda service stations, RAASC-RAAOC graduate C.R. Cox is in the health food business, and on a larger scale RAE graduate R.L. Bricknell heads the project management company which constructed the Paradise Centre, Ramada International Hotel and Marriot Resort on the Gold Coast. Other areas of venture ranged from J.G. Dorward as Staff Captain Pilot for Ansett overseeing the introduction of the Airbus into service to P. Costello as a crew member of Alan Bond's winning Americas Cup team, and L.J. Hiddins' venture into television as bush tucker man. The list is endless, matching the extensive range of skills, abilities and interests of the diverse group of individuals which made its way through Portsea and left the army earlier or later to pursue other employments and interests.

The founding commandant had indeed given the graduates high standards to live up to in the motto he bestowed on them: Loyalty and Service. The School attempted to bring this ethos out in the cadets in the hope that it would develop through their careers. With most it worked, others faded, and such being human frailty from which the broad spectrum of graduates was not immune, some black sheep strayed to activities which brought them to the wrong side of the law. The array of still-serving graduates occupying senior positions in the army were mentioned earlier (see supplementary list as at 2010), and those listed in Table 19, Table 20 and Table 21, bear testimony to the dedication of Portsea's best to service to their country in a profession never notable for remuneration and perquisites remotely approaching those in the private and more recently the public sector.

As for those who left, they had still taken with them the skills and ethos which were grounded at Portsea. Some of the best talent, as well as much of the worst or most distorted, moved into other public, private or individual service. Loss of the former could be ill afforded in an army which had to make do with the officers available until newer graduates moved up, but it was inevitable that a percentage would make the change for whatever reason. A notably arrogant attempt was made to stem resignations in the 1960s by refusing to accept them on the basis that, by applying for a commission, an officer had bound himself to the army until it no longer required him. This was inevitably reversed, and all those who had been refused left anyway, with an additional flow of others: the concept of loyalty was seen to be applied one-sidedly. Separation was unavoidable as graduates’ priorities changed, and the largely insensitive personnel management of the army provoked them to seek stability or at least a career path where self interest could share equally with dedication to work. However, enlightened personnel management practice has long accepted mobility between employers: the army's particular hurt lay in the impracticability of lateral recruitment. The problem was accentuated by inability to either bring itself to alter its authoritarian practices or provide adequate conditions of service to offset the disabilities of service. Still it was not necessarily a national loss, as one successful businessman put it 13:

From a narrow perspective it could not be said that the Army got full value for the six years of fulltime schooling ... however I hope and trust that my overall contribution to the army and to ... industry has shown a net positive return as a whole. I have certainly paid plenty of tax, and much of that was on money which my company earned from Japanese developers. That is, they were export dollars in every practical sense.

Many graduates attribute their later successes to the grounding they received at Portsea. While success is dependent on much more than initial schooling, those who had adapted to discipline and to a discipline built a sound basis for a successful approach to life and work. Tertiary education is about training the mind, and a trained mind is a precursor to successful problem solving and management. OCS provided that background. With the additional bonus of an understanding of men and the nature of leadership started at Portsea and consolidated in their early service, commodities all too rare in a bureaucratic and commercial world where self interest and cronyism tend to predominate, graduates were well equipped to succeed in any area if they had the twin sparks of real ability and motivation.

Taken over the thirtyfour years of its existence, graduations at OCS saw a wide range of abilities, skills, strengths and weaknesses which launched its alumni into the real world of soldiering and other endeavours. Some fathered sons who themselves became graduates; others came from families with a strong military tradition; some enlisted in the army and found a vocation where their potential was recognised and directed to officer training; others yet again had no connections with the armed services, electing this different career after finding little satisfaction in other areas of employment. A majority of graduates looks back on the time at Portsea with an element of nostalgia, remembering mainly the good things, but above all there is a great pride in both having come from such a well respected academy, and having been good enough to pass through its uncompromising testing and tempering of capability and character.

Make me a poem

(Portsea revisited 13 December 1985 14)

Make me a poem he said,

thirty four lines for thirty-four years.

And straightaway appears

a company of themes,

glorious thoughts, spacious phrases,

lofty and noble

as the halls they housed you in.

Thin fabric for a poem, I said,

Alma Mater praised beyond meaning

yet again. Hailed in odes

hollow as empty hallways,

barren as wind-scoured battlegrounds

buttressed above a thunder of sea.

No, wait, he said. For me

it’s not the place that holds a meaning,

nor victories, slight as they were,

nor debacles heaped flagpole-high;

and landscape revisited shapes no wish

to have it all again.

What, then, I asked,

knowing how his thoughts ambushed him –

jungled memories, greenlit bonds of friendship,

deaths, betrayals,

loves not sanctioned in a western world,

and the juggernaut of time.

There should be a poem, he said,

thirty-four lines for thirty-four years.

And straightaway appears

the essential legacy from drills and curtailed freedoms.

Out from the regimented maze

this fact remains sentinel:

That certain friends are here enjoined to prove

enduring trust, fidelity and love.

Jo Robertson

References:

1. AA MP927 A259/18/29 of 19 February 1951.

2. AWM MSS 1479 A84-11912 of 20 December 1984.

3. AA B2453/1 R284/1/lof 21 January 1969.

4. AWM MSS 1479 A182/R2/12 of 31 July 1967; Army List 1953-70; Corps List of Officers 1952 onwards; RMC Archives Commandants' Graduation Addresses 10 June 1977; Letters Australian Defence Advisers Malaysia, Papua New Guinea; Interviews J.P Cutler.

6. Letters R.L. Bricknell, I.W. Coombe, O.M. Eather, D.N. Thornton; Edwards P. Crises and. Commitments, p174f; SCMA Armyrec Printout Korea, Malaya, Borneo.

7. Inteviews J.O. Furner, P.F. Kent, I. Throssell.

8. McNeil I.G. To Long Tan p41f, 68f 179f, 230f; SCMA Armyrec Printout Vietnam.

9. Smith H. ed Peacekeeping Challenges for the Future Appendix ‘Brief History of Australian Participation in Multinational Peacekeeping’; SCMA Armyrec Printout United Nations.

10. Smith et al Peacekeeping Appendix; SCMA Armyrec Printout United Nations.

11. Editorial 'Australia in Papua New Guinea’ Australian Journal of Politics and. History 1990; McQueen N. 'Beyond Tok Win: the Papua New Guinea Intervention in Vanuatu 1980’ Pacific Affairs Summer 1988; HQ RFMF 10/38 of 5 January 1994..

12. OCS Journal June 1971, p17; AA B2453/1 R534/1/3 of 22 November 1967.