Chapter 7

Recreation and Social Life

Australia was, to some degree at least, defended on the playing fields of Portsea. Sporting activities were part of both the training curriculum and recreation. The Army recognised the value of sport contributing to physical and mental fitness and as well to developing teamwork and some aspects of character, so inclusion of team sports in the weekly programme was axiomatic. But fit young men had a rather wider view of sport as elective recreation so many, as well as enjoying most of the scheduled activity, of their own accord engaged in a variety of other sporting activities as time permitted. Such activities depended a coincidence of personal preferences and availability of venues, equipment and time.

Time was a major enemy in the sporting programme. The course syllabus, with its commitments, away visits and training and scheduled leave wrought havoc with commitments to participation in regular competition. The other was timing: the twice yearly graduations and between-course breaks occurred neatly in the middle of both summer and winter seasons, so vital games had to be forfeited and for the second half of a competition a substantially different team was available as the seniors left and new juniors joined. Successful teams found themselves speculating on and hoping for a degree of talent in the next entrants, and that the intake would be large enough to provide the range of players needed for the various sports. The School approach varied between one extreme of withdrawing from structured competitions and playing one-off games against suitable schools and colleges, and the other of going all out to participate in whatever sports could be accommodated with as many teams as possible. There were many combinations in between, including individual members participating in local teams as individuals, as well as local occasional games and the standard internal OCS inter-subunit derbys 1.

Sporting venues were at first a problem. With no playing fields and no prospect of permanency, the sensible course was to use someone else's, and Flinders Shire Council was quite amenable to augmenting its income by leasing Portsea oval provided it could be used when required for occasional use by local teams. For the cadets this was a satisfactory temporary solution if they did not mind the trip from the School to there and back, naturally on the run to get there in sufficient time for a session after classes, and to get back in time for a cold shower and dinner; at least the journey back gave the opportunity to duck into Ma Hill's store for some fudge. As for other sports, the local tennis, basketball, badminton and squash clubs made the cadets welcome and the Rosebud swimming pool was hired, so some diversity from field sports was possible until the construction of the School's own tennis, basketball and badminton courts could be effected. Not that there was any rush to do this given the tenure problem, and the developing OCS sporting ovals themselves bore tribute to much sweat by the cadets in building them before they got to play and sweat on them.

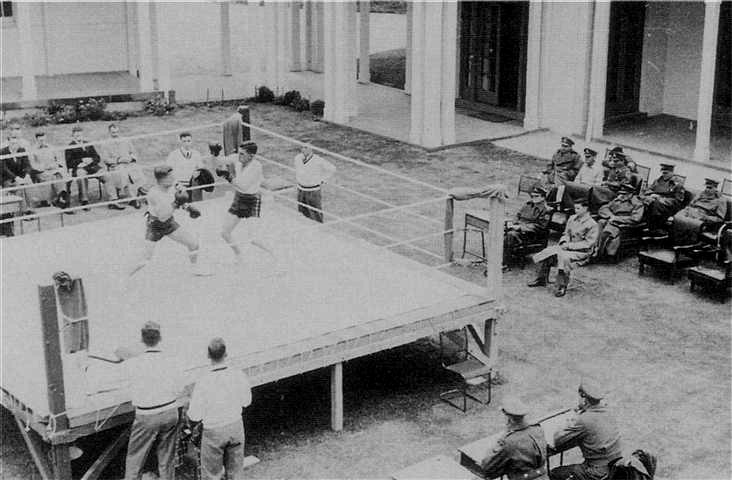

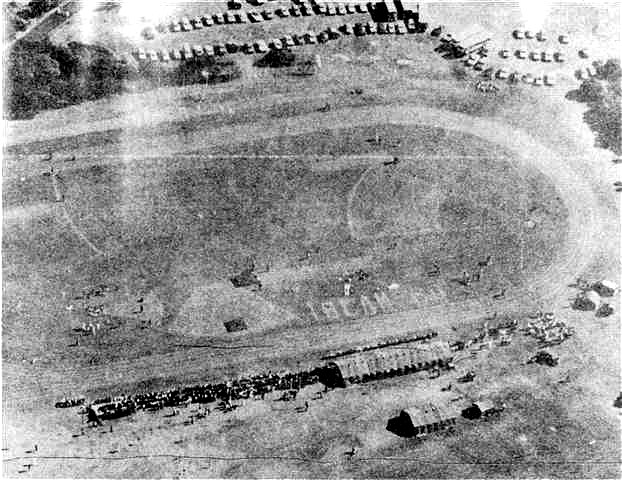

Inter-platoon competition dominated the sporting scene for the first few years. The obvious sports dominated this: cricket, rugby, tennis, hockey, swimming and the less universal sport which the army at the time considered a prime moulder of character, boxing. Athletics quickly became a leader in external competition, beginning with an internal meet for the first course, then branching out on the second to a contest at Point Cook with the RAAF Academy and RAN College. First called the Triangular Athletics Meeting, then successively Inter-Service, Combined-Service and Inter-College, it was firmed as ISCAM, the Inter-Service College Athletics Meeting, incorporating RMC and the RAAF Flying Training School (later replaced by RAAF Engineer Cadet Squadron) the inaugural sports being at RMC on 7 March 1959, then on annual rotation at each campus. In addition, OCS from 1961 gained recognition of its status by inclusion in the Lafferty Cup, a postal-results athletics competition between the military colleges of the Commonwealth of Nations. Given the preliminary training, practice against Victorian Amateur Athletics teams, state inter-service, inter-unit and intra-unit meets, and potted sports competitions, athletics was a pervasive sport at Portsea in the first half of each year.

If not as pervasive, rugby union was at least as compulsive during the winter. Beginning with the obvious forays against RAAF Academy and RAN College, the visiting RMC Second Class in August 1954 extended the scope, followed by a return bout at RMC the next year, when a team was also entered in the Melbourne B grade competition. The RMC match became annual, opportunity being taken of the industrial and military demonstration visits which both institutions carried out in New South Wales and Victoria. However smallness of numbers and the interrupted year restricted ambitions until the bumper classes of the 1960s encouraged another attempt at the Melbourne competition, which again ran up against the barrier of the disrupted season. Rugby's heyday came in the 1970s when three teams entered, one minor premier in 2nd grade 1970; in 1973 the three posted 20 wins from 21 fixtures between them, then faded as the forfeiture bugbear tore down the successes of matches won – it was frustrating to have the capability but not the opportunity to fully capitalise on it.

Supporters of Rugby's competitor, Australian Rules continually bemoaned the lack of support which their teams had in the heartland of the code. While their day of triumph came in 1973 when they played the Rugby 3rd team at one half rugby, the other Australian Rules and won both halves, they were unable to field an XVIII in a regular competition and had to be content with inter-company and some social matches against Police Cadets, Army Apprentices School and minor local teams. The real outlet came with individuals participating in the local teams in the Nepean League where by 1984 they commanded 10 places in the Sorrento team, the regular matches giving a sense of purpose to their efforts. Similar problems to both other codes afflicted the devotees of Soccer, who were strengthened by the increasing numbers of Asian-Pacific cadets but found it difficult to sustain teams in competitions with mid-season turnover of players and forfeitures. In some years they played with the Rosebud team, in others faced the frustrations of aborted competitions, being mostly content with inter-college and social matches.The other popular field sport was hockey. Well supported by both Australian and overseas students, it was a regular team effort from the beginning, entering Melbourne competition in 1962 and winning its division against the usual handicaps two years later and again in 1970, thereafter entering two teams and learning the lesson of the other sports of overstretching resources. Teams ended up in the Mornington competition where they were able to arrange extra games on weekends to cover absences and so were able to enjoy the continuity and the success which so often eluded the other field sports, regularly making the finals and often winning.

Rivaling athletics, swimming had its own Inter-Service Colleges Swimming Carnival. Popular early in the School's existence, at least in the warm weeks, it started with intra-unit, then inter-college events with RAAF and RAN Colleges, expanding in 1972 to the ISCSC incorporating RMC and the RAAF Engineer Cadet Squadron, again rotating between colleges. Other sports featured – if not great in numbers they had staunch adherents. Tennis, cricket, basketball, squash, badminton and golf, some managing on social competition, others on a training only or ladder competition basis. Not necessarily a sport to many, the cross country race was a standard term event for all comers, which meant everyone, as was the inevitable boxing, while such other diversions as judo and orienteering made spasmodic appearances. Sailing was given a fillip first when Torrent Yacht Club welcomed cadets as visitors in 1961, then in 1972 a Corsair dinghy from Amenities in Vietnam provided another recreational outlet for aficionados in free time when that could be found. Rifle shooting had an obvious attraction for those whose appetites went beyond range practices in the training syllabus, with some successes in inter-service and inter-club competitions, and the obvious side benefit, not lost on some, of going directly on leave to Melbourne after competitions at Williamstown. .

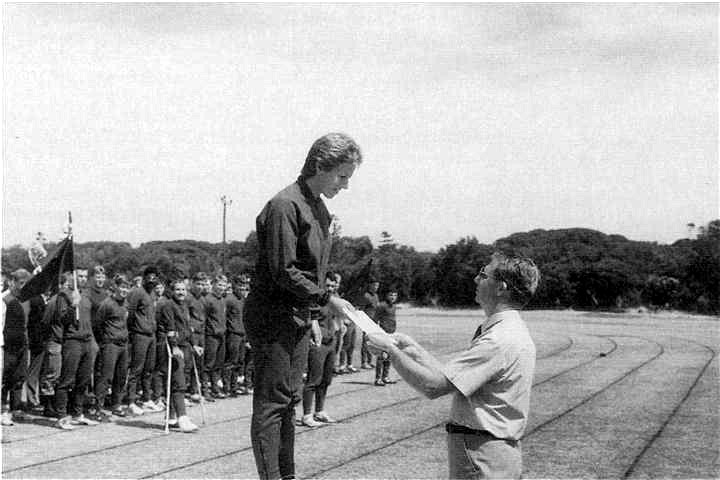

Inter-platoon and inter-company events remained the core of sporting competition. Held on most weeks over a range of mainstream sports, they settled ownership of the major trophies, after success in which a CSM or platoon sergeant often found himself adding swimming to the day's event with an involuntary dip in the Bay. The other standard derby was the Portsea-Point Cook Trophy encompassing Athletics, Swimming, Hockey, Cricket, Tennis and Rugby on an annual points system. For the scheduled activities the School awarded a variety of group and individual prizes. The prize list grew through the years, generous patrons providing a seemingly endless array for internal and external contest, some of which fell into disuse, others continuing on. The main trophies competed for within OCS and awarded on a bi-annual basis were:

The Rowell Shield 1955-85 Awarded to the platoon gaining the highest aggregate points in military and sporting competitions.

The Harrison Cup 1955-85 Awarded to the platoon gaining the highest aggregate of points in sporting events.

Champion Athlete/Sportsman 1952-61 Awarded to the cadet who was the best overall performer at sport; replaced by

Medals/Medallions 1961-85 Awarded to cadets who excelled in various sports; first started as a silver medal, upgraded in June 1963 to a gold medal with silver and bronze medals also awarded.

Winners of the Harrison Cup, champion athlete and top medals are listed in Table 3. The Rowell Shield results are shown in Table 10.

OCS was from the start dry for the cadets, the legal drinking age in Victoria then being 21, so with a number of the students being beneath that age it was decided that the fairest solution was to deny it to all. This was a difficult restriction for young men whose average age was over 20, and who had in either military or civilian life been used to consumption of alcohol as a routine amenity of life. It was therefore inevitable that they would find their own various ways of at least partially slaking their thirst. Publican Aunty Grace at the Continental Hotel proved most cooperative, making available a private bar and banning OCS staff from it, the purpose of which would not have escaped the deductive prowess of the School hierarchy, but they were sensible enough to leave well alone in the knowledge that controlled evasion is preferable to uncontrolled excesses. Of course a single watering hole will never satisfy determined topers, so their attentions were spread further afield when time off from their coursework so allowed: while the Nepean, Portsea, Sorrento and Continental Pubs met local needs, opportunities away from the School during visits, leave or absences were unlimited 2.Social life on the campus gradually developed a more settled schedule. While time was always at a premium in such an intense and purposeful programme, it was well recognised by the staff that social outlets were necessary not only for the emotional well being of their charges but also that potential army officers needed to develop ease and accomplishment in etiquette and mixing at all levels. Etiquette was included on the course programme from the start, receiving special emphasis during the regime of commandant Col J.G. Ochiltree, but that requirement was universally accepted. Dining-in nights provided the venue for practising formal dining, this being extended in the second half of 1961 to mixed formal dinners, with their partners and the officers and their wives attending. Balls were at that stage a usual means of entertainment, not only the regular graduation balls at which the pips were pinned on the graduates by wives, friends and mothers, but also others for which an occasion presented: sports or autumn ball and spring ball. The year 1952 was not a vintage year for army balls: a bereaved new queen having thoughtlessly ordered a full year of official mourning for the death of her father, this was interpreted to the maximum by old-school senior army officers and no official social functions were held, although permission was given, in a way reminiscent of religious dispensation, for graduation balls; a similar foolishness caused cancellation of the first 1953 sports ball on the pretext of the death of the dowager queen. Fortunately the populousness of the house of Windsor was outmatched by its members' longevity, and thereafter social programmes became more predictable, although in the years of small classes the scope for formal functions was limited 3.

Dancing was a particular interest of Co1 J.G. Ochiltree who strongly believed that 'the military ballroom is no place for the amateur', arranging for cadets to learn ballroom dancing as a compulsory activity for the junior class. This extra tuition was organised in consort with a group of mothers of girls who attended private schools, who shared the Commandant's view in relation to their daughters' future debuts, and so were more than happy for a co-operative venture. Each Friday night the junior class was packed off on a bus to Sorrento with Ochiltree's daughter, also due for her coming out, to join the other daughters, nicknamed Sorrento Brownies, for lessons from the mothers who were coincidentally also able to provide adequate supervision. After this lapsed when the girls had achieved their purpose, officers wives organised by Mrs Nola Hockings, wife of the Quartermaster and previous RSM Capt C.R. Hockings, continued giving tuition and another cooperative venture was struck with Toorak College at Frankston; this scheme returned to local talent in the mid 1960s with a group of young women dubbed the Dragon Squad, until dancing habits changed with the advent of the rock era, though there were later repechages for deb balls in the 1980s 4.

Organisation of functions was effected by a cadet social committee, and with increases in inmate numbers in the early 1960s a standard half year programme included two mess dinners, a mixed dining night followed by a dance, two balls, two informal parties, and four church parades followed by a buffet luncheon for wives and friends, averaging one a fortnight which was about the limit which could be fitted in between the activities of the School. Additional pre-graduation functions of cocktail parties, informal dinners, informal parties, corps drinks and graduation church services progressively expanded the six-monthly list, providing not only as active a social programme as other School activities would allow, but also a subtle avenue of furthering social education 5.

Arising from the Victorian reduction of the legal drinking age to 18 in 1965 came relaxation of the drinking embargo at Portsea, allowing sensible drinking at licenced premises from the hitherto restriction to port after formal dinners and licence at graduation. Then as another facet of normal living, a wet bar was opened in the cadets' ante-room the following year, though for limited times on holidays only. Taken a step further under the liberalisation of 1969, bar hours were extended to all weekday evenings and through weekends, though the embargo on liquor in cadets' rooms remained. Wine was also served with evening meals by mess stewards if required, and more formal wine appreciation was fostered by beginning mess wine and dine evenings in late 1972 6.

From an initial miserly two weekend breaks which was all the short courses could sustain, the full-year course provided scope for month-long breaks after the June and December graduations, extending progressively towards leave weekends in February, March, Easter, August, September, October and November 7. Adding up the social programme and sporting, demonstration and educative visits plus a later introduction of adventure training, there was plenty of scope for a varied lifestyle, beyond the routine of drill and ceremonial, a diet of academic tuition and the rigours of field training, designed in combination to produce fitness of spirit as well as mind and body.

Commandants generally held sincere and strong religious beliefs and made it their business to promote religious observance in the same way as had their predecessors since 1788. Church parades were a standard part of army life, providing an opportunity not only for members to participate in religious observance but also for inspecting officers to award further punishments for those deemed improperly dressed. For the first courses time constraints precluded compulsory parades being scheduled, cadets being free to attend church services on available Sundays as they chose, but extended courses allowed pre-graduation church parades and services. Then a mid-term parade was introduced, with monthly services on the campus. While many members had strong religious leanings and welcomed these and other opportunities for exercising their faith, many were nominal in their beliefs, and another small group recorded no religious beliefs. It is instructive to consider that it was felt necessary to use a coercive approach, with cadets being obliged to parade, after which those wishing or consenting to be bussed to the local churches doing so, while those declining were effectively punished by given other duties to perform or sent to their rooms. Military Board policy was for individual freedom of choice to worship or not to worship, but the reality was something different 8.

Policy on religion at Portsea by the middle period was based on a presumption that 'religion is the basis of character and integrity, which in turn is the basis on which leadership depends'; from this premise it was easy to move from a requirement to be on church parades to encouragements to attend the following religious services. At one stage it was proposed than any officer or cadet declining should have to apply to the commandant in writing, with provision for any exemption to be noted on personal documents. While this was stated as being to obviate future embarrassment to the member and the army, it is hard to see why a non-believer should be embarrassed by not attending church, why the army should be embarrassed over such non-attendance, or why indeed it was even necessary to apply for the freedom guaranteed by the Military Board Instruction. The end result was to place vulnerable cadets at a considerable disadvantage in exercising their right to worship or not to worship, the operative word commonly used publicly being 'strongly encouraged' 9.

Sectarian difficulties which had periodically occurred in the army were still in evidence in the 1970s. While the separatism of earlier years was ameliorated, and ecumenical trends had led to provision for united religious services, achievement of them was another matter, as the Conference of Chaplains General generally restricted such services to days other than Sunday to encourage members' attendance at denominational services. Commandant Col P.G. Cole was bent on the ecumenical approach but was disappointed when the Church of England chaplain opted out of the combined Anglican-Other Protestant Denominations services which had been usual; similarly his attempts to get a united service on the parade ground during the December 1977 graduation week, without mentioning a non-participation option, foundered on the Roman Catholic chaplain general's dissent on the grounds that it would detract from the Graduation Mass which was a dedication of the graduates of his faith. Attempts to organise drumhead services with all cadets on parade persisted, contrary to both the earlier Fox Committee recommendation against compulsory attendance at church services, and Chaplain General Holme-Moir's caution that combined services 'not be associated with compulsory church parades' and 'must be divorced altogether from any action of compulsion', eventually coming to fruition in the 1980s 10.

The main religious event remained the graduation church parades on the Sunday preceding graduation in June and December each year. These comprised a parade followed by church services: Church of England and Other Protestant Denominations at St John's Parish Church Sorrento, and Roman Catholic at St Mary's Star of the Sea at Sorrento. The School always desired to recognise the significance of the spiritual occasion by having a chaplain general officiate at each, in the same way that a general officer or vice-royalty invariably officiated at the secular occasion of the graduation parade and presentations, but apparently other priorities existed, and more junior chaplains often had to suffice 11.

While it was preferred that entrants to the course be unmarried, there was no prohibition on married members, so selection boards tended to select applicants simply on their personal merits. Indeed RMC cadets who married and were thus debarred from continuing at that college were offered a transfer to OCS. The few marrieds in the first entry in 1952 did not opt to bring their wives to the area during the course, but later students began to take a chance on the problems. Some cadets were married during courses, which was no more encouraged than was application for entry by married men – what was required was that those intending to marry first seek permission, which requests were met by counseling to defer the nuptials until after graduation, in most cases a sensible suggestion, but one which was sometimes avoided by not seeking permission. Such secret weddings often remained secret, others became common knowledge, but sensible staff members turned a blind eye to such victimless breaches of instructions to which there could be no sensible disciplinary response 12.From the outset there were much more tangible problems administratively as no entitlement for a removal at public expense existed for moves of less than six months, so families had to find furnished accommodation on the local market at the going rates in a holiday resort without rental assistance. Added to this was the education factor: soldiers' children were all too used to broken school years and over-frequent changes, and this short duration stay merely added to the disruption and trauma. When the course was extended to eleven months in 1955 the limited removal option was open – family and limited effects, while rental assistance allowed cadets to rent reasonable standard furnished accommodation in the Sorrento-Rye area and, for the January entry children at least, a full school year; fortunately school age children were few, as those of June entrants would have faced four schools in two years, a situation which made most long army courses coincide with the calendar year.

Particular problems arose with the RAAF married cadets in July 1975 and 1976. All were married but their previous units had advised them not to take their families to Portsea, instead of seeking advice from the School first. This resulted in noticeable problems for the students, so arrangements were made to ensure that proper advice was relayed to later Air Force entrants to avoid a repetition of unnecessary problems not only to families but also in the cadets' approach to a hard course with the additional burden generated by a year of separation 13.

The other real problem lay in the School's lack of recognition of cadets' married status and family needs: for 17 years they were given no leave to be absent from the school premises whatsoever, other than the general two leave weekends per half year. This may have had some validity for the short courses when waking hours were well filled with continuous activities, but the one year courses brought considerably lower pressure, and even allowing a progressive move towards monthly weekend leave, this was small consolation over the course of a full year. The result was of course married cadets absenting themselves illegally to see their families, with resultant punishments for those caught out. That some more rational approach had not developed before the reform process from 1969 is a remarkable commentary on yet another of the old world attitudes which persisted for so long amongst senior officers 14. Its effect on the morale and performance of married cadets alone, much less the marital strains and desperation which it caused, should have caused some earlier rethink of this hostile approach.

Even after married cadets were permitted and encouraged to join their families whenever not specifically required on the campus there was a major problem for wives, with husbands absent from daylight to dark, and then also for evening and weekend work, exercises and trips away. The initial loneliness until they met each other and began to develop a social life of their own was a problem which commandants' wives and those of other staff members attempted to alleviate by inviting them to morning tea to break the ice, then combined activities were organised for the wives of officers and cadets. Tennis, badminton and other sports, card parties, lunches, fashion parade with some of the wives as mannequins, sewing sessions and artistic activities were used to fill the all too frequent gaps in family life, but this was a luxurious world compared with the bleakness of that of their earlier sisters.

The weekly routine varied according to domestic circumstances. With usually one car to share, a wife had to drop the husband to first parade at 6.15 am then attend to children, domestic tasks and some to full or part time jobs in the area, then collect the husband in the evening. On Saturdays, with the cadets usually committed to work in the mornings, only occasional shopping forays to Frankston were possible, but the afternoons were also designated for sport, so some family contact could be retained by the wives attending the competitions. For entertainment Dromana drive in theatre was a last resort when dances, dinners, parties and balls were not on the social calendar. While the strains on some families may have led to domestic problems or to fall off in school performance or even contributed to the odd exit from the course, on balance, as was shown with the RAAF students, it was far better that the families accompanied the students, at least during the rational years 15. As difficult as the comings and goings of the husband and father were, the environment was supportive, and even the limited family life available was preferable by far to yet another year of separation in a service life which promised more of the same in future.

To many of the cadets there was a large social gap, ensconced as they were in a hard and unforgiving environment without family support, old friends, feminine company or any other source of tea and sympathy. Into this gap stepped a variety of likely and unlikely friends. Ma Hill of the corner store was more of a surrogate mother than a shopkeeper to the earlier classes, while Aunty Grace of the Continental Hotel earnt her sobriquet for being more than a publican. Still another group emerged in the families who took on overseas cadets who were amongst the most vulnerable, providing them with family and social outlets. While New Zealanders are great survivors and, having only slight differences to overcome, probably fared better than many of their Australian colleagues, the Asian and Pacific area students had cultural and linguistic hurdles to add to those in the School. Without the ready camaraderie which the anglocelt cadets had to lean on, the support of families of the Mornington Peninsula and even Melbourne taking them on weekends and holiday breaks solved what could have grown into a serious problem, given the steady increase in the range and numbers of overseas students 16.

As well as families such as the Matthews and Giulieri who built up a debt of gratitude for their fostering efforts, Lions and Rotary clubs on the Mornington Peninsula invited overseas cadets as dinner guests or speakers, while the Lions Club of Sorrento organised and funded an annual overseas student tour of the Ballarat-Bendigo area. During the month-long end of term leave some of the overseas students went home with Australian cadets, while others made their own pace, visiting other states and staying with compatriots. A modest sum was provided by the School from public funds to assist in holiday travel to allow and encourage them to make the most of opportunities to see the country and absorb some of its outlook 17.

Once an unavailable luxury, the programme progressively began to allow a degree of free time, and while some frittered it or used it for course related activity, many of the cadets used it to the full in such activities as treks, car rallying, orienteering and flying, yet more sport such as sailing, skiing and surfing, or simply just lost weekends. Active young men and latterly women could always find old and new ways to disport themselves. There has always been a remarkable facet of the army community: the mind-stretching range of skills, abilities and interests resident in any group of its members. The students of the COC were not lacking in this and within the constraints of their course indulged them to the full.

References

1. The following paragraphs on sporting activities are based on AA B2453/1 R723/3/1 OCS Reports 1952 onwards, OCS Journal 1971-85 and individual contributions.

2. Interviews R.G. Lange et al, I.C. Teague, D.J. Anspach.

3. AA B245311 R723/3/1 OCS Reports 12 July 1952, 17 December 1952, July 1953 et seq; December 1961;

4. Letters E.J. Ellis, O.M. Eather, Interviews D.J. Anspach, P.D. Asbury; OCS Journal December 1983, p48.

5. AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports December 1961 and onwards; OCS Journal 1984, p54-5.

6. AA B245311 R133/2/8 of 20 September 1969; RMC Archives OCS Scrapbook 1973-73.

7. RMC Archives Miscellaneous OCS Forecast of Major Events July-Dec 72, Jan.Jun 73.

8. AA B2453/1 R723/3/1 OCS Reports December 1955 and onwards; R130/3/1 Nominal Rolls; Military Board Instruction 240/2 Religion in the Army.

9. AA B2453/1 R719/1/3 Formal Church Parades (unpublished); AA B2453 1 1 R719/1/4 of 11 August 1975.

10. AA B2453/1 R71911/4 of 11 August 1975; R274/3/5 of 27 January 1976.

11. AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports December 1955 onwards.

12. Interviews R.G. Lange; Letters A.J. Ferguson; AA B2453/1 R130/3/15 passim.

13. AA B2453/3 R130/2/2 of 28 July 1976.

14. B2453/1 R133/2/8 of 4 April 1970.

15. Williams K. 'A Wife's View of Portsea' OCS Journal June 1971, p36; Mialkowski P. 'A Wife's Impression of OCS' OCS Journal June 1972, p57.

16. Interviews D.J. Anspach, J.P. Hunter; AA B2453/1 R133n117 Brief on Orientation and Entertainment Foreign Military Students of 26 March 1974.