Chapter 20

Esprit de Corps

The Men

The essential fact about the Corps was that it was composed of men, men who were citizens first and soldiers by vocation or duty. As happens in any cross section of members of a community, the nature of the men varied in every conceivable way – in background, upbringing, education, skills, temperament and performance. Some made outstanding soldiers, most fair average quality and some few were as worthless in the army as they had been in civil life. But overall they proved their worth, both as a team and as individuals where they made an effort in so many ways, not just the specialist tasks expected in their particular trade, but also in just about every conceivable situation which could and did arise, where there was always someone who knew how to do something or was prepared to try his hand at it.

It was recognised from the start in the Victorian and New South Wales Corps that a particular type of man was required, and special recruitment was undertaken together with higher rates of pay. This little bit of elitism, and the implicit recognition of their importance by their respective commandants stopped them being relegated as mere grocers, as happened so easily in the Navy, and got the beginnings of esprit rolling. A similar appreciation in the beginnings of the Commonwealth force kept this going – they were not to be the leftovers from other regiments and corps but carefully selected from appropriate backgrounds and given proper training and encouragement. There was never a problem amongst the Army’s leaders in recognising both the essential nature of the AASC, its units and their sterling performance until the World War 2 emergence of a massive structure in the Australian base diluted its image as a battlefield operator. During World War 2 the British Army had given a lead by splitting the Army into ‘arms’ and ‘services’, and this was exacerbated in the dominant post-World War 2 Australian Regular Army by an increasing number of pretenders, of various corps backgrounds, without either combat experience at responsible levels or the ability to profit from that of others. To magnify their status these fostered a caste system which embodied their own corps and others into the group called ‘arms’ – now forgotten as being short for ‘fighting arms’ – which added on to the true fighting arms of infantry and armour such others as Signals, Survey and the non-combat majority of Engineers, which simply provided services that did not involve fighting. Of course ‘arm’ has always meant ‘arm of the service’, which included all combatant regiments and corps including RAASC, but this exercise in false elitism tended to relegate RAASC and other essential and effective corps into the second and by implication inferior group ‘the services’, rather than accepting that all non-fighting organisations belonged in the obvious complementary classification of ‘supporting arms’.

While in the 1930s an army leadership with war experience had no problem in passing over RAA and RAE to allot the tanks to AASC as a competent, mounted combatant corps, this later development had serious problems in status, quality and career development of RAASC’s members. It was very common in the 1960s for infantry soldiers with some physical or other problem to be recommended by the staff as a matter of course ‘for transfer to RAASC’. While this was in a way a backhanded compliment, it nonetheless required some strenuous measures by RAASC command corps representatives to head off this thoughtless action from creating a serious dilution of its standards, readiness and capability as a corps which also had to operate in the combat zone. An outline of their trades and duties has been covered progressively through the previous chapters in context and pictorially. The diversity is immense, even within their soldierly and technical responsibilities: operating and controlling road, rail water and air transport and air delivery; growing, catching, buying, storing and distributing foodstuffs; acquiring, storing, packing and distributing petroleum products; and distributing ammunition; odd occasions of fighting as infantry, commandos, cavalry and gunners. And always having to operate in the military environment, blending trade and commercial skills with the military ones, usually having to look after their own domestic needs, responsibilities and security well after the supported units had been stood down.

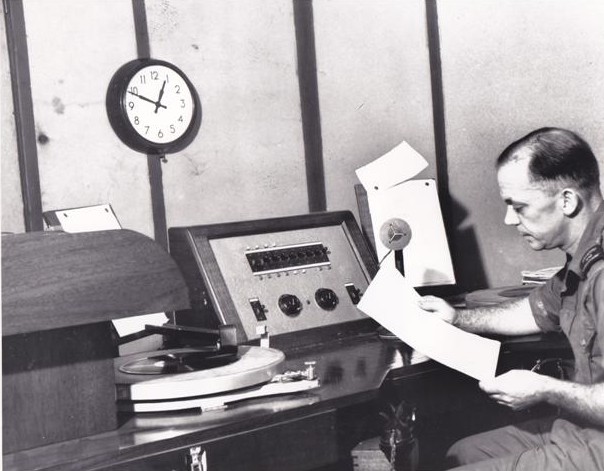

In other areas the variety of occupations performed and changes in direction was diverse and illuminating of the talents and flexibility of the individuals concerned. Those of earlier DSTs were covered in Chapter 17; many activities are described incidentally to the mainstream stories in other chapters. Other interesting diversions included a group of AASC officers taking over the Intelligence function in South Australia in the early 1930s; Maj L. Logan late of 1 Cav Div AASC formed the Papuan Infantry Battalion and commanded it from 1940-42; city boys learnt to handle horse transport and in turn 8 Aux HT Coy provided the bulk of members for 2 Bulk Pet Storage Coy operating at Milne Bay in 1943. Some as prisoners of war were escapologists, joining local resistance groups, or making precarious voyages and treks to return to United Nations-held territory; others had a temporary stint in guarding prisoners of war at Tobruk. Members produced newspapers in both wars, begun with unit newsletters on board troopships and ending with Aussie for the first AIF in France and Tobruk Truth for the garrison. Corps members were pressed as radio announcers, and organisers of sports and race meetings and social events. On the sporting side AASC units often figured prominently in inter-unit competitions, usually against numerically far stronger units, and produced higher level athletes such as Lt W.J. Humphreys who represented Australia in the 880 yards run at the 1950 Commonwealth Games. And so the list goes on. The variety of tasks and activities which came the way of units and individuals and were generally handled successfully is virtually endless, but in keeping with the diversified talents and can-do approach fostered in the Corps.

This variety and pervasiveness is not surprising when it is remembered that the Corps comprised over ten percent of the Army and, by the nature of its tasks like its Commissariat predecessor, was to be found just about any place where there was an army element. This is not realised by most people, including ex-Corps members, as the AASC/RAASC tag is rarely mentioned in historical or media portrayals for many reasons. Some of the more hackneyed photos in this book have been specifically included to put this tag where it belongs, and readers can well recognise such connections in future by becoming alert to the incidence of Army Service Corps appearances in so many events. For example:

When the sinking of the hospital ship Centaur and loss of doctors and nurses is commemorated, think of Lieut S.B. Westhorp and 40 men of the AASC transport section of 2/12 Field Ambulance who also went down with the ship, one fifth of the total.

In the movie A Town Like Alice the fictional hero declares himself a truckie – which MT Company?

People whose father or relative ‘was a transport driver’, ‘was a medical driver’ but haven’t made the connection.

The well known but unrecognised Banjo Paterson and the unknown and unrecognised Bill Doolan.

The endless photographs with bland captions which, examined with a bit of thought, are so obviously AASC units getting about their business.

All these and more are a part of the major, essential, distinguished but unfortunately unrecognised and unsung record of the Corps and its members. This book is dedicated to redressing that gap, but it can only be successful if a wide spectrum of ex-members and the RACT fosters such ongoing recognition of their proper place in the Army’s doings and history.

Corps Traditions

Every organisation has its myths (fictitious explanations), legends (traditional stories) and apocryphal tales. A longstanding myth resided in the teachings of Corps history in Corps indoctrination of new members: this was confined to the British ASC and its predecessors, ignoring RAASC’s own clearly defined beginnings and development in Australia from 1788 and the Victorian Corps’ preceding the unification of British officers and soldiers into a single corps in 1888 by two years; and indeed even largely ignoring AASC’s existence before the post World War 2 period, as if some mystical event had transmogrified whatever unmentioned arrangement was there before into the RAASC. It was just too easy to use some one else’s already written history rather than research out our own, even when the sponsors had lived part of it themselves. Two articles in the Australian Army Journal in 1950 and 1952, from the Directorate of Supplies and Transport, purport to be about the RAASC but in fact not only give straight British Army historical background but also barely mention the RAASC even in the contemporary context. Hugh Fairclough’s Equal to the Task contained some pre-World War 1 background material on the Australian Corps, some taken directly from English historian Beadon’s History of the RASC which has a short and reasonably accurate sketch of colonial origins, and some hearsay, but the beginnings of pioneering work in Browne and Anthony’s scholarly articles in the Australian Army Journal 1972-73 appeared only in the RAASC’s last year of existence 1.

While this deficiency was both remarkable and reprehensible for its lack of self esteem and pride in the Australian Army’s own Corps, there is no doubt that the RASC and its predecessors had a significant, ongoing and mostly beneficial influence on the Australian counterparts. Doctrine, organisation, dress and insignia have all leant heavily on British models, partly through habit, partly sycophancy and partly because of the inherent soundness or appropriateness of the example provided. It was not until very late that some United States Army influence appeared – indeed the US Army Quartermaster Corps in World War 1 was in tutelage to the RASC and AASC; its later influence was principally in such technical areas where it had come to excel – materials handling, aerial delivery and fuel distribution.

The origin of the Corps motto Par Oneri, a rendering of which forms the title of this book, is unclear. Fairclough assumes that the first Staff Officer Supply and Transport, Movement and Quartering (in itself an error – the appointment was Director of Supply and Transport), Capt J.T. Marsh ASC, selected it in 1913 2; its presence on the 1906 badge disposes of that speculation, but still does not provide the author, occasion or basis of selection. As a distinctive departure from following the British lead, its provenance is all the more intriguing, and in contrast to slavishly copying the RASC badge in 1952, with the appalling decision to remove the Corps motto in favour of the Garter one. An unattributed statement on an MGO Branch insignia summary claims the motto was adopted from the Victorian ASC, but no direct evidence can be found to date, other than a 1910 Army List entry above Victorian-based officers of the AASC, three years before that on which Fairclough relied, but still much too late.

However some circumstantial evidence exists in an 1896 direction by the Victorian Defence Forces Commandant for units and corps to prepare stationery crests, including a motto, the ASC being allotted the colour dark blue. It would seem that Par Oneri arose from this exercise, although it is not recorded in the Victorian Military Forces Regulations. On the other hand the NSW ASC generated a badge carrying the inscription Advance Australia worn at the turn of the century, so avoiding the matter of a motto. To imagine that they were trying to pre-empt adoption of their Victorian rival’s motto may be taking conspiracy theory a little far, but Par Oneri won out by 1906, for whatever reason and from whatever source, when the sealed pattern of the AASC badge was lodged along with those of other unit and corps with the Ordnance Department in Sydney 3.

A myth given some credence and unfortunate repetition arose from a tale in Chester Wilmot’s story of Tobruk: ‘As a reward those who fought as infantry were given the right to keep and carry bayonets they had won in the field. They value this highly, for bayonets are not issued to the ASC’ 4. This nonsensical concoction flies in the face of equipment tables, the visible evidence of photographs with ASC members wearing bayonets and doing bayonet training from at least 1891 onwards, and the existence of trophies for AASC bayonet fighting competitions; the simple fact is that drivers’ bayonets were held in their unit quartermaster stores for issue when required, being a hindrance when worn in vehicles. The statement is equivalent to saying that, because the infantry sharpen their bayonets only when warned for operations, when they do go on operations they are therefore granted the privilege of carrying sharpened bayonets. It was a silly patronisation which tends to denigrate the training and performance of so many AASC soldiers under fire in several wars and is best consigned to oblivion. The rolls which appear in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 tell a more accurate story which some other prominent corps and regiments might well respect and envy.

Like most Corps, RAASC has had its nicknames and epithets. World War 1 spawned Ali Sloper’s Cavalry, Army Safety Corps, All-night Corps and, for the over-age remount men, Methusaliers; from World War 2, Galloping Grocers and Nervous Corps; others such as Petrol Sniffers did not gain wide currency, but later Wheelies, Peas and Beans and Posties became common. Some of these implied a certain lack of enthusiasm for the Corps’ location on the battlefield or lack of warrior image. But while some other corps tried to conceal the obvious fact of their function being no more than providing a service well away from the fighting by calling themselves ‘arms’, the ASC had always been proud to declare its role, and striven to excel in providing a service to the genuine fighting arms, not hesitating to enter the battlefield in fulfilment of those tasks. Much of the name-calling was in the way of banter, in the same vein as such epithets as Drop Shorts and Shirt Lifters applied to another corps. A corps without such titles is like a man without a nickname or familiar name – without character or not worth the effort.

Most organisations aspire to some literary recognition of their efforts. AASC had the benefit of Major Banjo Paterson, a squadron commander in the remount units in the Middle East 1915-18. His poem The Army Mules 5 ends:

And if you go to the front line camp where the sleepless outposts lie,

At the dead of night you can hear the tramp of the mule train toiling by.

The rattle and clink of a leading-chain, the creak of the lurching load,

As the patient, plodding creatures strain at their task in the shell-torn road,

Through the dark and dust you may watch them go till the dawn is grey in the sky,

And only the watchful piquet’s know when the “All-night Corps” goes by.

And far away as the silence falls when the last train has gone,

A weary voice through the darkness calls: “Get on there, men, get on!”

It isn’t a hero, built to plan, turned out by the modern schools,

It’s only the Army Service man a-driving his Army mules.

A less well known Ambonese folklore verse commemorates the heroism of Driver Bill Doolan in the Japanese assault on Laha airfield in 1941; the first part translates as:

On the first day of February an Australian soldier climbed into his strongpost;

Thousands of soldiers of Japan lay killed or wounded

by the great guns, machine guns and rifles of the Australians on Ambon.

One Australian named Doolan killed many men of Japan;

He did not run away or move back until at last he was killed by the men of Japan.

The Australian named Doolan died by the side of the road,

His grave is under the Gandania tree.

The Corps has had its recorders in other fields of the arts as well. The Australian War Memorial maintains in its collections a variety of paintings of AASC subjects by war artists including Arthur Streeton, Will Dyson, William Dargie, David Barker, Frank Hodgkinson, George Lambert and Ivor Hele. And as well as amateur efforts of so many individuals, official war photographers including Frank Hurley and Damien Parrer, plus an unnamed legion of public relations, press and television cameramen in Australia and overseas have recorded its activities in peace and war. The musical side is covered later in this chapter.

Appointments

The Corps appears to have survived its first and most difficult half century quite well without patronage. While an effort to gain royal patronage made some progress immediately before World War 2, this was suspended and was not readdressed seriously until after the war. Apart from the leisure to think of such matters now being available, there was a precedent in the British Army Service Corps having gained its royal prefix in 1918 as recognition of its sterling service in World War 1. The AASC had been a young corps operating in tutelage during that war, but in World War 2 had performed with distinction in its own right. This was therefore an opportune time to seek a corresponding distinction, particularly as the feeling within the Australian Army was then favourable to entrenching alliances with the British Army and the Monarchy. A Warrant signed by King George VI gave the title Royal Australian Army Service Corps on 1 January 1949. Prince Henry Duke of Gloucester, former Governor-General of Australia, was appointed Colonel-in-Chief in 1953; to represent him in Australia an Honorary Colonel was appointed 6. Increasing ill health prevented the Colonel-in-Chief from revisiting Australia during his colonelcy of the Corps so all real representational duties were assumed by the Representative Honorary Colonel. Even so, practical difficulties in the single Representative Colonel meeting the diverse and often competing ceremonial needs of such a dispersed corps led to the appointment of additional honorary colonels to assist him. Two were appointed in 1968 with the intention of extending this to one in each state 7. This extension had not been effected by 1973, however those appointed provided some measure of predictable and reliable representation at appropriate occasions in each area, with the effect obviously of considerably greater value than that of unseen higher titular appointments. These honorary appointment holders are listed in Appendix 6.

The designation of the practical (as opposed to titular) head of the Corps changed several times. Sir Edward Hutton’s desire to establish such a staff head of AASC in 1903 was frustrated by politically-directed Head-Quarters staff reductions, so it was not until the 1912 reorganisation that a custodian was appointed as Director of Supply and Transport and Chief Instructor AASC Training. The post-war officer shortages saw an interim Staff Officer Supplies and Transport, Movement and Quartering, re-designated as Director when a suitable incumbent could be found. At the beginning of World War 2, hiving off the Movement and Quartering functions returned the position to Director of Supplies and Transport which stood until the separation of the two functions in 1972, when an interim Director of Transport bridged the changeover to RACT in 1973. These staff officers sustained several hats, the major ones being Head of Corps and Head of the Supplies and Transport Service, with earlier ones also carrying Chief Instructor AASC Training and the supply and transport staff and training functions for 3rd Military District 8. A list of incumbents is included in Appendix 6.

Of the Corps directors, one name stands out in several ways. Not only did R.T.A. McDonald fill the position of Head of Service three times, over a span of 20 years, in three different ranks from captain to brigadier, but he also had the onerous task and privilege of carrying it through the difficult early World War 2 period, and then again during the later period of maximum war activity. His dedication and sheer hard work guided a badly underprepared staff function, and service function in the field, from potential failure to resounding success. The man was not, however, without his foibles and failings: tales of his unorthodox behaviour abound, as is always the case with great men. Hugh Fairclough relates with approbation his technique in handling importunings, during visits to units, by taking copious notes, then discarding them without action afterwards 9; this is, of course a signal crime in staff officers, to raise expectations which then degenerate into despair and loss of respect for the system by those who have to make the Army work. While there is a lesson to be read from this negative attribute, it should not obscure the very significant and tangible results of his administration of the Supplies and Transport Service. That he should receive no official recognition (his OBE was awarded in 1928) is an unfortunately accurate commentary on the recognition generally accorded to successful members not only of the Corps but also of the supporting services in general. Quartermaster General Cannan, when publicly denouncing AASC commanding officers for the lack of decorations awarded to their members, missed the point that his DST had been similarly ignored, however Cannan himself received no recognition either, and awards to staff officers other than in field formations were rare 10. McDonald has been suggested as ‘father of the Corps’ 11 which, if not strictly accurate, at least acknowledged his long term and beneficial influence on both the AASC and the Supplies and Transport Service.

Alliances

In order to foster fraternal relations with the armed forces of allied nations, the Australian Army has allowed and encouraged the formation of official alliances between regiments. Close relationships between the AASC and ASC and their predecessors, dating back to the Commissariat, the Colonial Corps, and the Maori, Soudan and Boer Wars, were subsequently cemented in World War 1 and already resulted in many informal and personal connections. This relationship was formalised in 1921 by alliances between the AASC and the RASC, the Canadian, the New Zealand and the South African ASCs, then continued with the RCT when the RASC was disbanded in 1968 12. The necessity of these alliances is questionable, as the long close association with British and New Zealand counterparts in particular, built up in peace in war, and a mutual respect for each other on both a personal and group basis, already provided a bond more tangible and durable than an artificially contrived one. The alliances did however provide an official seal on what was already a well recognised reality.

Corps Associations

Immediately after World War 2 a group of senior AASC officers in Melbourne decided that positive steps should be taken to preserve active service experience from dissipation and eventual loss. Meetings were held regularly, and as a natural extension in 1947 the Victorian RAASC Officers Association was formed under the leadership of Col H.M Frencham to give serving, reserve and retired officers the opportunity of continuing a tangible link with the Corps and, at the same time, the means for developing their wartime friendships 13. With encouragement from DST, similar associations were formed in the other capitals, and as time moved on their activities encompassed social and charitable activities as well as the quasi-military ones.

Attrition and fading interest and health amongst the wartime members eventually began to change the early 50-50 ratio of serving to retired members and, in the smaller states in particular, efforts to keep the associations viable placed pressure more and more on participation by serving Regular and Citizen Force officers who really had no need of more parades. The military relevance also faded, becoming instead a briefing of the veterans on the activities, techniques and equipment of the current army. Some associations became inactive, reactivated and inactive again. Annual dinners filled the needs of the majority, whilst the old soldiers continued to retain their fraternal gatherings at Army depots and elsewhere as it suited them.

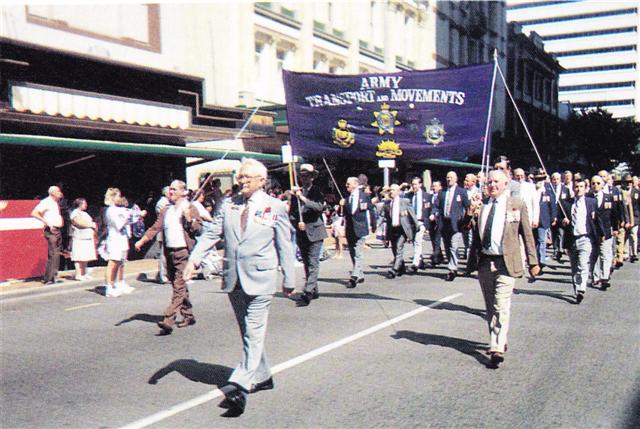

More durable associations arose within some units. Perhaps the most prominent is the 8th Division AASC Association, whose members had a particularly special experience to share. The Association has branches in each state, holding regular reunions and watching over the welfare of its members. A more recent one from the war in Vietnam, the Tea Spoon Club took its name from 1 Coy’s operators of the woefully underdesigned 2½ ton tippers which had to suffice for the construction effort in the first two years; this group maintains strong cohesion and marches under its own banner at appropriate occasions. Still other associations have been formed outside the immediate wartime influences, around Citizen Force units in their regional areas. In a future time where the logistic support side of the Army has to be expanded to match the combat side, the old units will no doubt reappear on the order of battle and it is to be hoped that such associations will ensure that detailed and accurate unit histories are prepared and preserved so that resurrected units have available to them their background, traditions, service and operations records, back to early Federation times, on which to build. The Australian Army has copied so much from the British Army, but rarely that which is perhaps the most important – the unit tradition which contributes greatly to esprit. As was the case in RAASC units, most RACT units’ knowledge of their background is sparse and RACT, as a corps which has not so far been to war, misses out if it fails to lean back on its predecessors. In consequence members are not inculcated with the fact that they belong to units with a proud lineage and tradition to uphold, and a record of service equal to or bettering many of the so-called arms units. It is an important gap to be filled.

Appendix 10 Corps Associations

Colours and Flags

The Corps colours of blue, white and gold were taken from those of the Victorian Ordnance, Commissariat and Transport Corps. The provenance of these is not clear, the myth of their having come from the British Army Service Corps failing on the irrefutable basis that the Victorian Corps predated the British ASC. There would be little doubt, however, that the Victorian colours were selected from the same shopping list. The British ASC’s colours are said to be derived from the blue of all the early uniforms, the gold facings of the Commissariat (1834) and the Royal Waggon Train (1819), and the silver facings of the Military Train (1856) 14, but it is worth noting that silver was prominent in the uniforms of the Royal Waggon Corps (1799-1802), Royal Waggon Train (1802-1819) and Land Transport Corps (1855) 15 so perhaps the tradition has its roots a little earlier. Whatever the finesse of their lineage, the colours have been incorporated in Australian Colonial and Commonwealth uniform cloth, facings, stripes and other appendages; badges and other insignia; and in flags, blazers, sports wear and neckties.

There are two corps flags on record. The basic design was taken from the RASC flag, being of standard dimensions 5ft by 3ft, comprising equal vertical panels in the Corps colours of blue, white and gold with superimposed in the centre panel the Corps officer pattern (that is, multicolour) badge. That flag was modified in 1960 by superimposition of the RAASC Corps motto Par Oneri, a move by Director V.E. Dowdy to rectify in some degree the reprehensible earlier removal of the Corps motto from the badge itself 16.

Badges and Insignia

The known range of Corps headdress and collar badges, those of the Colonial Forces in general use, and of the Australian Imperial Forces and and Australian Commonwealth Military Forces in general use in wartime, are summarised in Plate 1. Other distinctive insignia include buttons, buckles, gorget patches, badge rosettes, shoulder and epaulette titles, some represented in Plate 2; colour patches are in Plate 3. Skill badges authorised for different periods are shown in Plate 4: these were mostly in general Army use for the trades and skills involved, except for the Air Dispatch Brevet introduced in 1969 as a specific RAASC insignia 17. It is not contended or intended that these illustrations are a definitive statement of Corps militaria as there are many variants and deviants from the basic range shown here.

Further examples of badges and insignia are shown in the uniform plates and in various photographs throughout earlier chapters. The RACT Museum is building a collection to which specialist collectors, enthusiastic amateurs and bower birds can contribute their knowledge and artifacts.

Uniforms and Accoutrements

While the Colonial and earlier Commonwealth uniforms particular to the Corps are fairly easy to define, a growing variety of dress – general duty, field, working and protective uniforms shared by the whole Army – begins to blur distinctions from World War 1 onwards. Badges and titles became the main distinctions, and for some periods even these were in abeyance for various reasons. The wide variety of uniforms and orders of dress used during a period of over a hundred years makes it impracticable to describe or illustrate them all, and to these must be added the individual and unit quiffs which were common but not strictly regulation; the illustrations are merely representative of the range, and generally not exclusive to the Corps other than by colouring and embellishments.

Plate 5 Colonial Uniforms 1863-1903

The uniform worn by the Waikato Regiment’s Australian volunteers serving with the Commissariat Department and Commissariat Transport Corps was the blue jacket called a jumper, blue trousers with a red welt at the seams with leggings, pill box forage cap and leather accoutrements standard to the Regiment, but with a red band to the cap 18. Commissariat staff with the New South Wales Soudan Contingent wore the standard blue NSW Military Forces uniform with white helmet and puggaree, and were issued after arrival with the British khaki drill trousers, jacket, helmet and leggings 19. NSW and Victorian ASC volunteers in the Boer War wore the uniform of their regiment, while the special service officers wore their normal colonial unit dress and the khaki field dress of the theatre 20. The Victorian Ordnance, Commissariat and Transport Corps began with a blue helmet and uniform with white facings and gold lace; the Commissariat and Transport Corps on leaving the tutelage of the gunners switched to khaki helmet and uniform with blue facings and trouser welt; and the Army Service Corps reverted to blue uniform with gold lace and white trouser stripes, white helmet and puggaree or blue forage cap, 21. The New South Wales Commissariat and Transport Corps and Army Service Corps dress comprised the same blue uniform and white helmet, but with white edging on jacket and epaulettes and piping on cuffs and white stripes on the trousers 22. A compromise version of these blues continued to be worn by the AASC in those states as dress uniforms after Federation, even though the other state components adopted the Commonwealth khaki dress. Working uniform included khaki breeches, pullover cloth leggings and a slouch hat with blue and white puggaree.

Plate 6 Commonwealth Uniforms 1904-1942

The standard Commonwealth uniform adopted on 1 July 1904 was the prototype of the familiar khaki woollen Service Dress which lasted until the adoption of Battle Dress in 1951. The basic dress was designed both as general duty dress and, with the addition of shoulder boards, sashes and aiguillettes, as full dress, so meeting the proscription of a federal Defence Minister against some officers as looking ‘like refugees from a Turkish harem’. AASC khaki uniforms were embellished with white edging of the shoulder straps plus metal corps and company number titles, corps sleeve titles in blue, and white gorget patches with a blue braid centre line (no braid for Volunteers); helmets and slouch hats had a khaki puggaree with a single white fold (later changed to white hat band with blue centre stripe) and white rosette behind the badge; caps had a white band, again changed to white with blue stripe. Initially AASC members, as with all corps other than mounted infantry, were provided with breeches and puttees, but as a mounted corps this changed in 1908 to the more utilitarian leggings and bandoliers. NSW and Victorian components continued with their blue dress uniforms instead of the add-on paraphernalia; all were issued with canvas working dress 23. During World War 1 the AMF component at home retained these uniforms and embellishments, but the AIF adopted a more relaxed service dress and removed corps distinctions, standardised on the rising sun badge and identified corps units by colour patch.

From 1930 the basic blue uniforms affected in 2nd and 3rd Military Districts became standard walking out dress for all AASC, the original service dress with divisional or specialist corps colour patches becoming general duty dress. World War 2 brought a universal return to the World War 1 style service dress, khaki drill and later jungle greens, corps badges being replaced by the rising sun with universal buttons, both being oxidised for inconspicuousness. Colour patches again became sole identifier of corps affiliation, but proliferation of increasingly unrecognisable patches for lines of communication troops provoked overreaction to a single AASC patch in early 1945.

Plate 7 Commonwealth Uniforms 1940-1950

Plate 8 Commonwealth Uniforms 1951-1973

Return to corps distinctions in 1952 was limited to RAASC badges, sleeve titles, buttons and a gold lanyard: it was not until 1970 that white stripes on dress uniforms and corps mess dress were authorised. Battledress, khaki drill and in 1961 jungle greens replaced the old service dress as both general and field dress. Most sleeve adornments were removed from 1959, leaving the new service dress and wool/polyester summer dress of 1964 looking refreshingly clean and spartan, a fact not universally acclaimed, metal shoulder titles being subsequently resurrected 24.

As regional variations, RAASC members in Papua New Guinea from 1964 wore the juniper green drill uniforms originally allotted to the Pacific Islands Regiment; and the dark green used in Far East Land Forces was adopted for members serving there, carried across into ANZUK Force in 1971. A backdoor attempt to introduce multi-coloured stable belts for Australian members in that Force was aborted when the Senior Australian Army Officer delegated the decision to senior corps representatives; all but RAE were of the opinion that there was no Australian tradition for this form of dress and that Australian soldiers overseas should follow the strong tradition of the two AIFs – of being proud to maintain a clear national identity. It is only in peace that soldiers seek the glory of Narcissus rather than that of Mars.

Military Music

Military music came to the Army Service Corps in Australia with the establishment of a trumpeter within the NSW Commissariat and Transport Corps in January 1891, spreading to the Victorian ASC in 1896 as a trumpeter and bugler 25. But fashionable and necessary as these instrumentalists were in an army of visual and aural intercommunication, they fell short of the unit and formation bands which have always been part of the military scene. There were attempts to raise Citizen Force bands through enlistment of civilian bands in toto: the Brisbane Scottish Band was inducted as the Northern Command Troops RAASC Band in 1957, but disintegrated within a year. A more comfortable arrangement was experienced in Eastern Command where the Newcastle City Pipe Band had become the Northern Rivers Lancers Band in 1952; 16 Coy was a part of this unit and equally enjoyed its support until NRL was disbanded in 1956, after which the band became the 16 Coy Pipes and Drums, building a championship reputation throughout the State; it was a mutually rewarding situation for both the RAASC in NSW and the Band, which carried over to the RACT 26. For the other States, while the successful acquisition of bands would have been a useful adjunct, Corps units were always able to call on the services of Command and other bands for occasions when they were really required.

The RAASC corps march was taken directly from the British Army Service Corps which acquired it on a whim of the Duke of Cambridge 27, then Commander-in-Chief of the Army. At a parade at Aldershot in 1875 after a good lunch, when he directed that the ASC should, contrary to custom, also march past, he was asked what tune should be used; he replied ‘Wait for the Wagon’. Whether this was intended to be humorous or not is not recorded, but it stuck. It was used until 1945 when, due to its repetitious monotony, an expanded format incorporating The Regimental Call, a South African folk tune The Trek Song, and the existing Wait for the Wagon was adopted under the original title. This adaption still has some way to go in overcoming the original problem.

The music was composed by R. Bishop Buckley after he emigrated to the United States where he formed Buckley’s Minstrels. It was published in Boston in 1840 as a popular song; its subsequent publication by Macmillan in 1866 as an ‘old English folk song’ is questioned by both the earlier publication and its very obvious link with the mid-west genre of which the contemporary song Oh! Susannah is typical. Perhaps the theme may have had a folk song connection, however nothing is known of this. The composer of The Trek Song is also unknown. The adaption to incorporate the other components was arranged by J.F. Dean the bandmaster of the RASC Band, this arrangement being adopted by the RAASC in 1952 28. The words for both of the main components are too maudlin to be used in sober company or otherwise, and are consequently not recorded here. Sufficient that the tune itself is catchy, and in keeping with the spirit of the Corps. An official rendition was recorded by the Central Command Band and released under the Hume Broadcasters/5DN Adelaide label.

Artefacts, Memorabilia and Historical Relevance

A serious attempt to preserve any sort of collection of Corps artefacts does not seem to have been made before 1970, when a search for a GS wagon was conducted in Victoria. Efforts at unit histories for World Wars 1 and 2 and other periods have produced sketchy, patchy and mostly very defective results. There was apparently an attempt to write World War 2 Corps histories in each command in the 1950s, but apart from South Australia the products of this are no longer extant; the project which culminated in Hugh Fairclough’s book seems to be the only one which was pressed to fruition and preserved by publication. The clean-outs which tidy staff make from time to time have effectively disposed of most of the documentary and photographic material, while the lack of a retention policy left little equipment to represent the wide range operated by the Corps. And of course the continual chopping and changing of units has done nothing to encourage continuity or preservation of the past. It has been left to the RACT and RAAOC to attempt to remedy these neglects as best they can, given the serious losses of the past.

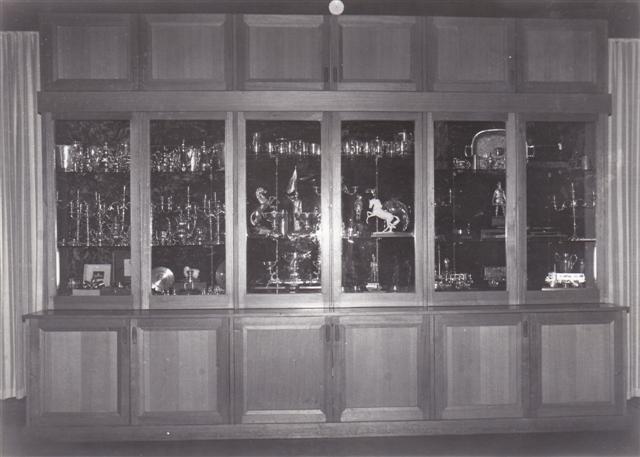

Some trophies and pieces remained, in some cases by inertia, in others by careful rules on custody. In the latter category are the silver centrepiece presented by the RASC and the collection of Corps silver. Other remnants exist in trophies, photographs, furniture of prominent Corps members and other memorabilia, some often rescued from other hands by those with a memory and feeling for the value of building the present and future on the worthwhile things of the past. A new wave of awareness of this seems to have emerged in some sections of the RACT, perhaps as part of a general increasing community appreciation of our heritage. A proper Corps Museum and unit collections are beginning to emerge slowly, and hopefully this may become more systematic and indeed more urgent, as the passing years each carry their toll of lost memories and material.

The past has many aspects: some are sheer antiquarianism, and although this rates little esteem with purist historians, it is always interesting in order to get a feel for the earlier periods and understand the great achievements of those men who managed to do so much with so little of the things we now regard as essential. Another is that of continuity and avoiding reinventing the wheel: each generation imagines it has invented everything that is worthwhile, and it is sobering and instructive to recognise that our predecessors have done it all before, often better. Sir Arthur Tange, in a moment of frustration with the senior officers facing him when he became Secretary for Defence, claimed that servicemen were ‘groping in the past’ to make up for their inability to think. While the incumbents may have justified this rebuke, there is also the opposite side of the coin where succeeding military generations somehow manage to avoid recognising that there is little new under the sun, that present problems have been handled before, often after bitter practical experience, and that it really is worthwhile to learn from that past experience, so saving the pitfalls and penalties of being historically illiterate and lazy. But perhaps the foremost benefit in a military organisation, which depends so much on morale, is the pride in unit and corps which can help maintain standards and sustain performance under the difficult circumstances which military life and activities create. A corps is a vehicle for esprit de corps and the Royal Australian Army Service Corps has fulfilled this admirably. To its successors go the heritage, the lessons and the responsibility.

Footnotes

1. Browne and Anthony 'NSW ASC' Australian Army Journal 1972, p32f and Browne 'AASC' AAJ 1973; a typical denigration prior to this is an article by and on the RAASC in We Serve 1955 when, after two pages of irrelevant Cromwell's baggage train and Newgate Blues, it dismisses the AASC half century, including two world wars, in a sentence. Little better is Willing R.T. 'The Royal Australian Army Service Corps’ Australian Army Journal June 1957.

3. Army List 1910; Victoria Military Forces GO 100/1896.

5. Kia Ora Cooee March 1918; Argus 16 January 1946.

6. AAO 99/1948; CAG No 76 of 26 November 1953.

7. RAASC Digest 1969, p21; CAG 62/1973.

8. CPP 1903 vol II Scheme of Organisation, p19; MO 269/1912; Army List 1925, 1926, 1941.

10. Fairclough, pxii; Long Final Campaigns p580.

11. RAASC Digest 1968, p2 Obituary: it is indicative of the deficiencies in Corps history that even this official Corps summary should miss his earlier appointments as Staff Officer Supplies and Transport, Movement and Quartering, and his 1939-41 period as DST.

12. MO 29/1921; RAASC Digest 1968, p4.

13. 'The RAASC Officers Association, Victoria’ RAASC Digest 1968, p41.

14. Crew RASC p316; also p30-2, 52.

16. RAASC Quarterly Bulletin No 5 1952, No 8 1953; the motto was added in 1960, RAASC Digest 1971, p115; apart from the nonsense in the first half of that article, note the plural in the title, and the implication that the RAASC somehow shares the UK motto when it has its own.

17. Army Dress Manual 196S, para 91f.

18. Ryan & Parham Colonial New Zealand Wars p107, 142; Featon Waikato War p68.

19. Sutton Soldiers of the Queen p55, 221, 224.

20. See various photographs: AWM, State libraries, periodicals.

21. V&P Vic LA 1987 No 72; 1889 No 36 Part l, s11; General Orders 252/1890; 24/1896; Victorian Gazette 27 December 1889, 12 April 1889, 18 August 1892, 2 June 1893, 2 February 1894, 10 February 1896.

22. See image Part 4 cover.23. Army List 1910; MO 67/1912.

23. CPP 1903 vol II Hutton Report, p13; MO 261/1907, 16/1908, 100/1909, 672/1912.

24. AA B1535 755/l/93; Army Dress Manual 1963.

25. NSW Government Gazette 3 February 1891, p954; V&P Vic LA 1896-7 No 38 Defence Report, p22.

26. RACT Pipes and Drums Unit Brief; Bryant C.K.R. ‘History of the Pipes and Drums 16 Coy RAASC (Amph GT)' RAASC Digest 1962.

27. The following paragraphs are derived from Crew RASC p313-6.28.