Chapter 19

Training and Doctrine

Early Training Institutions

The basic building blocks of training from the inception of the colonial supply and transport corps were the selection of men with an appropriate trade background, unit training in drill and musketry, cemented by on-the-job training in adaption of trade and work skills to the military environment. This sourcing of skills worked well enough as long as a supply of suitable men and an adequate level of supervisory experience was available. It had not been a problem in the small Victorian Corps as its elements were raised and trained within formed artillery units and, initially at least, a permanent NCO assisted when they concentrated at camps. There was a temporary fall off in experience in the early 1890s, but the unit was well enough established to remedy this with selective recruiting and unit training. In the NSW Corps, where the fostering system was not used, there was a slow build up until a base level of experience was assembled. From this base, with the addition of a permanent cadre under Maori War veteran 2Lt R.J. Beauman in 1894, a momentum was established which sustained the more ambitious scale of expansion and operation in that state 1.

Federal reorganisation in 1903 leant heavily on these established organisations. The other state components when raised, having nearly two decades of experience to catch up, were built up gradually through a base of garrison tasks. State Commandants were urged to get their AASC units off the ground by recruiting from:

Supply Branch: Bakers, Butchers, Clerks, Coopers, Grocers, Merchants, Slaughtermen, Supply Vendors, and Tradesmen connected with Forage and Produce Stores.

Transport Branch: Blacksmiths, Cab-owners, Carriage Smiths, Farriers, Horse Drivers, Saddlers, Waggon Builders, Wheelers, and men accustomed to the care of horses and to work connected with Forwarding Agencies and Carrying Firms.

With this fairly easy beginning for the AASC, the only real training problems encountered up to 1910 arose from lack of tactical practice due to over-reliance on contractors, largely due to the lack of military transport equipments 2. Although unit training, when reinforced by the continuity of permanent cadre and area instructors, coped well enough with the basic technical and military skill needs of the units, the training of officers and NCOs was a different matter. Hutton’s 1902 concept was to extend the existing limited all arms schools of instruction held in Sydney and Melbourne, the former to serve NSW and Queensland and the latter the remaining states; this scheme would then be extended to other centres on an occasional basis, to suit local requirements. For technical training, separate schools were to be established, including an ASC School authorised on 12 August 1902, which were to operate on the same basis as the all arms schools. The ASC School was incorporated into the 1903 reorganisation plan, which designated the permanent staff of the AASC in NSW, headed by Lt M.McD. Lyons, as the instructional staff for AASC courses, which were to be conducted whenever and wherever required 3.

Courses were held under military district general staff auspices, however Military Board and Inspector General reports highlight disappointing results from all schools of instruction due to over-rigid scheduling of courses and classes at inopportune times, so precluding attendance by a majority of militia and volunteer members. For AASC courses the effect was abysmal. Apart from a series of courses in Sydney in 1903 and 1905 and again in 1912 as a mass training programme for officers and NCOs of New South Wales, only the odd course was subsequently scheduled in Sydney and in Brisbane, and even they rarely proceeded; elsewhere there was nothing 4. The real benefit was achieved through the ‘mobile wing’ concept of Permanent instructors attending camps to assist in training, though on a less formal basis than the courses conceived in 1902. Training continued to be very much within units and on the job, and to the units and the quality of the men themselves must go most of the credit for the effective standards they eventually achieved.

Expansion Expedients

As noted in Chapter 2, standards fell away badly from 1911 due to the dilution factor. Restoration of the situation by 1914 was assisted by the appointment of additional instructional staff to help replace practical experience with learned experience. This was an all in effort from several sources, which replaced the School. The Director of Supply and Transport at Army Head-Quarters was appointed Chief Instructor AASC training and conducted courses in Melbourne; the Assistant Directors of Supply and Transport and their allotted instructors in the military districts also filled a similar function for their centres. The AASC in NSW again ran a series of courses in 1912 to train officers and NCOs for the Universal Training expansion. For the rest, standard programmes of training, exemplified by the initial one in General Order 130/1902 and later incorporating remedial action for weaknesses identified by the Inspector General’s staff, were provided as a basis for achieving the required standards. Where the General Staff schools and classes system earlier had largely failed the technical needs of the AASC, this system of special staffs assisted by the permanent cadre staff from NSW helped the AASC units come up by their bootstraps 5. That this was feasible rested on the relatively simple trades involved and the ability to get recruits basically skilled in those aspects, particularly as universal training began to feed in an adequate stream of young men knowledgeable in horse handling and the clerical, butchery, bakery, coachbuilding and blacksmithing trades; in an era when most boys joined the workforce by age 14, these skill levels were well developed in 18 year olds. The new officers and NCOs could call on those skills in their men and, if themselves possessed of the right qualities, quickly learn supervisory requirements from their tutors. It would not be quite so simple in the upcoming ages of mechanisation and aviation.

The first real expansion came with World War 1 where the general immaturity of Citizen Force members from the recent influx of cadet universal trainees, together with the prohibition on compulsory service abroad, necessitated raising of more broadly based volunteer expeditionary forces. The problem of generating supplies and transport support for these forces overseas was to a degree ameliorated by the British Army supplying the overall administrative structure within which the Australian formations would operate, but for the field role the existing AASC units had to be replicated in the AIF, and novel mechanised units raised and trained completely from scratch with little understanding of their function and techniques of operation in a major war battlefield 6.

The training system for the AIF in Australia was essentially one of induction, indoctrination and basic military drills and skills, although AASC units and reinforcements were required to provide supplies and transport support for the camps while also preparing themselves for departure. But to the AIF itself overseas fell the main business of allocation of tradesmen, and further technical, battle, NCO and officer, unit and formation training. This was foreseen with the raising of an AIF Training Depot with an AASC wing at Zeitoun in Egypt in March 1916, initially with considerable assistance of British schools and instructors, the AIF members progressively taking instructional positions as use of the schools and experience grew. This became a critical element in the rapid post-Gallipoli doubling of the AIF in Egypt 7. After the move to France in 1916, the throughput of the depots in England arising from the high casualty rates created ongoing training and retraining tasks of similar proportions.

Use was made of British instructors initially, and of the British ASC School at Aldershot for technical training. The AASC Training Depot was re-established at Parkhouse on Salisbury Plain, but its task was extended to providing the supplies, transport and barracks services support for the whole Australian depot complex in England plus hospitals and AIF Head-Quarters, housing, feeding and transporting about 50,000 men at any one time. The school itself was set up with a transport and a supply wing, training about 150 reinforcements and reassignments a month, feeding them through the base support role for practical experience as well as manning the structure, so killing two birds with the one stone. The AIF had learned during the Gallipoli campaign that the usual practice of getting rid of underperforming officers and NCOs to the depot system led to badly trained reinforcements and tradesmen, so by this time a system of rotating good quality members as instructors had been implemented, the performance of the AASC depot system reflecting this attention. The first commander, responsible for both support and maintaining the quality of reinforcements was Lt-Col A. McMorland, but when the duality and magnitude of the function was eventually recognised, an ADST position was created, filled first by McMorland, then successively by Lt-Col J.G. Tedder and Lt-Col A. Moon CMG DSO, original commander of 9 Coy and then of I Anzac Corps Supply Column. An officer commanding the training depot was appointed separately, first in 1917 Capt V.J.P. Hennessy from 30 Coy on its disbandment, followed a year later by Maj E.J. Munro DSO from 1 Div Train. Reinforcements were trained in courses at the transport or supply wing of the Depot’s school, then given practical experience in the units supporting the AIF depot system in England, then filtered to assigned units through divisional depots – essentially battle schools – at Etaples in France, relocated in June 1917 to Harfleur, where a separate divisional-corps-army troops depot handled non-infantry personnel.

While much of the AASC training was routine, calling on basic civilian skills readily available, the increase in motorised supply and ammunition columns necessary to support all five divisions with their own AASC units, effected in 1917, required special facilities which were aided by ASC Mechanical Transport Depots Bulford and Rouen, then establishment of the British Central Mechanical Transport Vehicle Driving School in France to handle all requirements. This system was so adequate that recruitment of drivers in Australia ceased in 1917, it being simpler to fill the need as it existed at any time in theatre. For the divisional trains of the mounted divisions in the Middle East, an AASC Training Depot was established at Moascar as part of the AIF School; it was here that the Anzac and Australian Mounted Division Trains were formed in August 1917 8. As there were no AASC motorised units in the Middle East, routine training at Moascar was essentially on horse transport, supplies and related artificer skills, with the local British school system available for advanced training.

A Permanent School

When the Army settled down to an expected long period of peace after World War 1 it could once again set about organising itself on a longer term basis. The level of availability of instructional, mechanical, administrative and catering skills in the civil community did not provide a ready source of acceptable operatives for the Army, so a part time school was planned for the tuition of Permanent staff, to begin with an ASC course in November-December 1924. Unfortunately the nominated Chief Instructor, Lt-Col J.H. Peck who had been trained in England to become DST, was diverted to another posting, and it was not until a year later that a part time School was established to conduct special courses, with Staff Officer Supplies and Transport, Movement and Quartering Capt R.T.A. McDonald allotted as Chief Instructor. The first course, ASC Course No 1 was completed at Sturt Street Depot in 1925; then ASC Supply, Horse Transport and Mechanical Transport Course No 2 in 1926 together with a Q Administration and a Cookery Course were conducted at the Sturt Street Drill Hall, the United Service Institute at Coventry Street and Broadmeadows Camp respectively, a matter which the Inspector General was anxious to label as a signal advance in his annual report 9. Separate ASC and MT Courses No 3 were held in 1927-28. Later in 1928 the ASC and Q Administration School was ‘permanently located at Sturt Street’, and given a formal charter ‘to instruct and train the permanent forces’, with four wings 10:

| ASC Wing | Technical AASC duties and administration |

| MT Wing | Driving and maintenance |

| Cooking and Catering Wing | Cooking and catering |

| Administration Wing | Movement and quartering, unit stores administration |

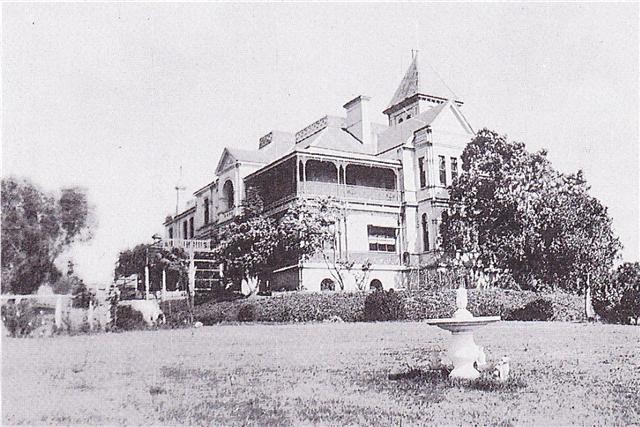

As was the case with all corps schools at that time, the staff was assembled, as necessitated by the course programme, from available instructors, in this case the Directorate and the 3rd District Base S&T Section with Capt McDonald still as Chief Instructor. In an effort to strengthen the school in the expectation of increasing mechanisation, Major E.A Wilton DSO and WO A.A. Browne were sent to England for training and on return in 1930 became Chief Instructor and MT Instructor respectively. In 1929 Cooking and Catering Wing continued to operate at Broadmeadows and the MT Wing split: two MT Sections had been formed to hold, maintain and operate the Army’s small but growing pool of gun tractors and task vehicles in Sydney and Melbourne. These sections provided the pool of vehicles for camps and the NCOs were also used as instructors for driver training of the Militia artillery, engineer, signals and AASC units in NSW and Victoria – No 1 Section at Paddington and No 2 Section at Sturt Street, the latter members also doubling as assistant instructors for courses at the School 11. The ‘permanent’ location of the School at the Sturt St Depot shortly became less so. Corps schools habitually conducted courses at a convenient Citizen Force depot, but the increasingly continuous nature of the ASC and Q Administration School programme, plus the equipment and training aids required, made this increasingly impracticable. The result was curtailment of courses from 1928 onwards, until a windfall capital gain from the sale of an unwanted property at Ascot Vale provided sufficient funds for another ‘permanent’ school and living in accommodation to be constructed in the northwest corner of Victoria Barracks Melbourne in 1930. The School operated from here, renamed as ASC Training School in 1934, until 1940 when the expansion of both Army Headquarters at Victoria Barracks and activities of the School necessitated its transfer to more practical quarters in Osborne House at Geelong with Lt-Col A.J. Stewart now Chief Instructor. Here it operated initially in four wings – Supply, Driving and Maintenance, Horse Transport, and Cooking and Catering 12.

Further Expedients

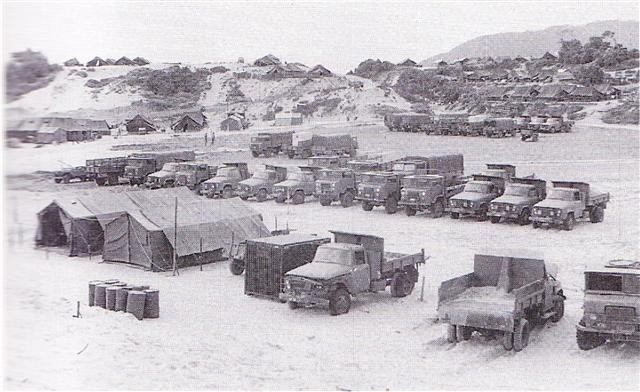

A year later the dilution factor of a rapidly expanded Army resulted in the School being reorganised to include a wing for officers and NCOs: the trade-oriented school was giving way to a training institution of greater depth. With the 1942 restructuring of the Army came the title change to Land Head-quarters AASC School with responsibility for officer-cadet training, food technology and workshop courses, the MT Wing having relocated to Fishermen’s Bend 13. Expansion and distribution of the Army had by now made it necessary to open other training establishments at home and overseas. MT schools mushroomed in each state, and overseas in each major formation. An AASC Wing of the Services Training Regiment of the AIF in the Middle East conducted clerical and catering courses from 1940 to 1942. The 1st Mobile School of Mechanisation was formed in Melbourne in August 1940 and sent to Palestine to assist in the establishment of the massive transport empire being built up within 1st Corps in anticipation of mobile operations in the Western Desert, returning in 1942 to join the LHQ AASC School at Geelong as its Mobile Workshop Wing. AASC Training Depots and units were established in each Command and military district to handle the influx of recruits and meet decentralised training needs and, for the special short response requirements of the field formations, an AASC School was established in 1st Army at Cabarlah, moving to Lae in 1944 14.

The end of the war collapsed these decentralised schools and brought a period of flux where staff and courses changed rapidly at the LHQ AASC School which was relocated to ‘Studley Park’ Narellan in August 1945 where it continued as the Officer Cadet Training Unit for RAASC and conducted supplies courses. In 1947 it moved briefly to Ingleburn where it conducted post-graduate courses for Officer Cadet Training Unit graduates and supplies and transport courses for permanent officers 15.

A Seat of Learning

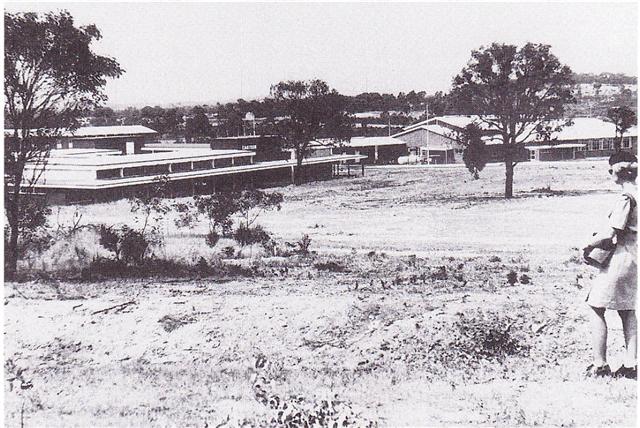

The AASC School was located at Puckapunyal in 1947 and renamed RAASC School the following year. Accommodation was in the galvanised iron huts erected for the AIF camp in 1940, but for all its imperfections was a stable environment which no one else coveted and so offered security from the previous evictions and disruptions. The run down condition of the area and buildings meant ongoing hard work by both staff and students for over a decade to reclaim the area from the semi-desert created by years of overuse and neglect. Puckapunyal was always known as a bleak and desolate place, but over years of effort its environment and amenities improved measurably.

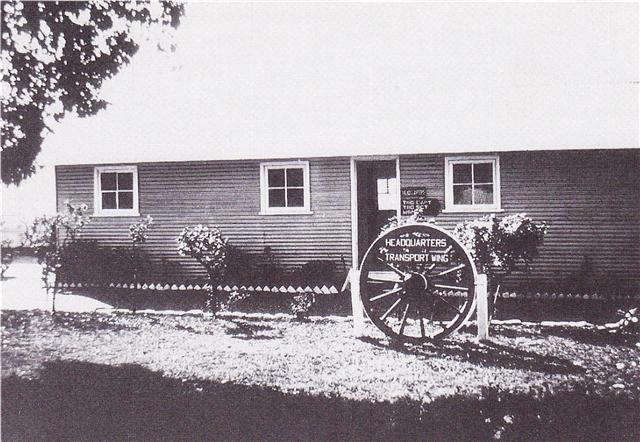

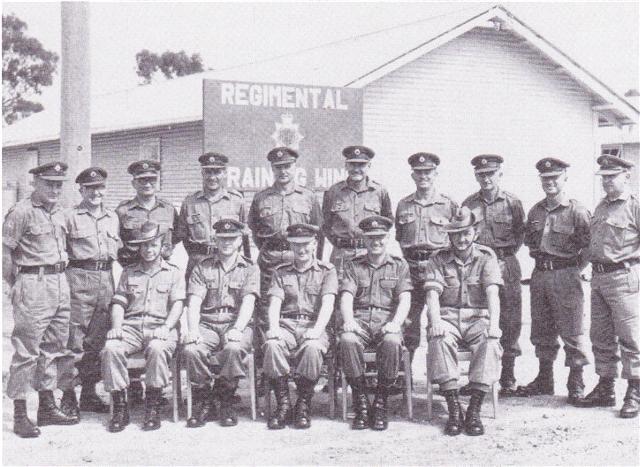

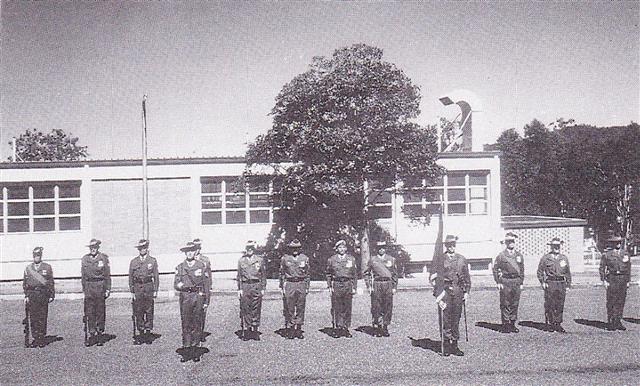

The School opened with Supplies and Transport, Quartermaster, Clerical and Cooking and Catering Wings. An RMC Wing under Col C.C Easterbrook DSO MBE MC was operated at the School in 1948 to qualify those RAASC members with wartime commissions, who wished to remain in the postwar army, for permanent ones. To complete the scope of Corps training a separate MT Wing was added in 1951, the Supplies and Transport Wing being retitled Operations Wing; the Air Dispatch Wing was brought in from the School of Land/Air Warfare at Williamtown and a Corps Training Wing was also established in 1958 to replace the basic corps training function hitherto run by 1 Coy, now transferred to 1st Brigade Group at Holsworthy. These moves concentrated all the main functions of previous schools under the one umbrella to form a cohesive teaching institution, retitled for this multiplicity of functions in 1960 as the RAASC Centre, controlling both RAASC School and RAASC Training Company. The arrangement coped until the pressures of expansion in the Vietnam era stretched the School facilities to breaking point, resulting in a detachment being established at Bonegilla from 1966 to handle overflow driver and catering training 16.

Establishment of any discipline on a permanent, professional basis is substantially reliant on a source of past, current and developing knowledge – a seat of learning. British doctrine and training material had underpinned the AASC until the Pacific phase of World War 2 forced development of techniques to cope with that environment and the novel obligation of self sufficiency, but this was essentially done on a needs basis to meet the expedient requirements of the war with the variety of purpose-oriented training units described previously. Establishment of the postwar Army brought to a head the requirements of tactical and technical training which became the primary function of an army now committed to preparing for a broader spectrum of scenarios than simply fighting the Empire’s wars. The decision to maintain a substantial regular component, together with the greatly increased technical content of warfare, dictated a larger and more formal training base, in which an RAASC School was a major element. This School went beyond the pre-war model of largely teaching drills, skills and administration, to providing the opportunity to develop tactical and technical knowledge and pass it on through training the officers and NCOs of the regular units and the cadre staffs of the Citizen Forces. The best of the Chief Instructors and the Senior Instructors of the wings of this new seat of learning made the most of this opportunity; the unimaginative ensured that the standards in some areas periodically slipped to unacceptably low levels. Overall, a continuing hard core of dedicated and able instructors and students maintained the flow of knowledge to the Army which was reflected in the ongoing success of the Corps where it counted – at the coalface in its responsibilities to the rest of the Army.

Decentralised Training

While the RAASC School provided a centre for officer, NCO and some specialised trade training, an effective means was also established for the basic trades in the raising of RAASC Trade Training Centres which mirrored the concept of the post-federation General Staff schools of instruction, the trade wings of the later Army Head-quarters ASC and Q Administration School and ASC Training School, and the various command and formation technical schools of World War 2 in their dispersed locations. Trade Training Centres modelled on those World War 2 units were established in 1952 in each of the mainland state capitals to train all arms drivers, clerks and cooks according to the needs of the Command which they served. Central and Southern Command Trade Training Centres serviced Northern Territory and Tasmania Commands respectively; Papua New Guinea used the Northern Command Trade Training Centre until its own all arms school at Lae took over in the later 1960s 17. There was also a bonus for the Commands as the Centres provided the structure to conduct all arms officer and NCO promotion examination coaching, and training, storeman and CMF MT testing officer courses: they furnished an economical and flexible means of training to suit the specific needs of each Command. Their worth was proved particularly during the Vietnam period, as infantry battalions and other corps relief-detachments under pre-embarkation training could have specially tailored short and compressed courses to bring their new drafts of recruits up to practical operating standards, rather than lose them for full length and unnecessary trade courses for such tasks as infantry company clerks and signals detachment cross-country driving.

Unfortunately the utility of these Centres was not obvious to those who had not been exposed to the practicalities of the real army, or reaped the benefits of their output, or taken the trouble to analyse the shoestring nature of their operation, or thought through what alternative means of covering their wide scope of activity would be needed and its cost. A particular Director of Quartering’s persistence in opposing their existence was rewarded with their demise in 1972. Training of the basic trades was centralised at the RAASC Centre at great cost in capital works and travel expenditure, with both quality control and flexibility lost to the user. The other functions of the Centres had to be picked up, manned by imposition of administrative and personnel levies on working units.

Following the custom of the colonial forces, a programme of overseas training was continued soon after Federation, at the Staff College Camberley and other courses in England, and with attachments to the Indian Army. Under this latter scheme AASC militia members Capt D.P. Young OC 23 Coy attended courses of the Indian Army and was attached to IASC units in 1912-13, 2Lt A. Matheson from 22 Coy following in 1913-14; this was repeated with permanent officer Lt E.M. Dollery MC in 1926-27. The problem of gaining a DST with adequate background, solved in 1912 with an ASC officer on loan, was to be resolved post World War 2 by sending an RMC graduate to the Staff College at Camberley, followed by courses at the RASC Officers School. Lt-Col J.H. Peck, then attending the Staff Course was persuaded to do the ASC courses and be interim DST until this solution could be implemented, but he was diverted to a Q Staff posting on return, later filling in briefly until Maj J. Northcott followed him in 1924-25 and then became DST; next came Capt F.L. Coldwell-Smith MC in 1927 but was diverted to the ASC and Q Administration School on the death of Maj Wilton; finally Capt A.P.O. White completed the training 1933-35, but he also ended as Chief Instructor at the School. To meet the requirements of proposed mechanisation Wilton and Browne had attended a mechanised transport course in UK in 1927, also returning for duty at the School. Lt G.A. Nichols undertook supplies training in 1937-38, returning as Deputy Assistant Director of Supply at Army Headquarters. Capt A.J. Stewart and successor Lt D.G. McKenzie, as OC 1 MT Coy and Instructor 1 Tank Section, both attended training in UK in 1938-39, both returning to successive brief stints at the ASC Training School before secondment to the AIF 18.

The pattern of training officers with the RASC was re-established after World War 2. The RASC Officers School established 12 month courses in each of transport, supplies and petroleum which provided the core of this training, a long succession of RAASC officers attending these to prepare them for technical postings in DST in those fields. For air delivery training, following acquisition of American cargo aircraft in the late 1950s, the expertise of the US Army became preferred, officers required for specialist postings undertaking courses at the US Army Quartermaster School at Fort Lee. These various courses were usually supplemented by attachments to units afterwards to gain additional practical experience. And to bring in more specific knowledge to substitute for a dwindling of experience in war, exchange postings between the RASC and RAASC and postings with the RASC in Far East Land Forces in Malaya-Malaysia were implemented. Over two decades the great majority of Regular officers of lieutenant colonel and above had undertaken at least one of these assignments, completed an overseas course as well as several at the RAASC Centre, and qualified at the Australian Staff College.

Inspection of foodstuffs was part of the supplies and transport function from the beginning. Although Inspector General’s reports were generally critical at the lack of expertise of regimental officers in food and forage, it was not until 1925 that formal training was introduced when Permanent staff and Militia supplies officers of divisional trains were cycled through food inspection courses conducted by the Victorian Public Health Department 19. To cope with the extraordinary expansion of supplies activities in World War 2 courses were conducted at the William Angliss Trades School at Caulfield and LHQ School of Food Technology at Randwick, the former continuing on in the post war era for permanent NCO inspectors. A requirement to upgrade technical training of officers for supplies specialist postings in DST, the Central Procurement Organisation in Melbourne and the Army Food Scientific Establishment at Scotsdale was met by attendance and qualification at tertiary courses at the NSW Institute of Technology, subsequently University of NSW.

Transfer of responsibility for the postal service from RAE to RAASC in 1966 without any postal units or specialists brought with it the requirement to train postal clerks, but the small numbers involved and lack of an instructor made it impractical to conduct this in-house initially. In consequence these members were trained at courses conducted by the Postmaster General’s Department at the RAASC Centre until 1968, accepting the disability of the coverage being basically PMG post office procedures. After this bedding in period the follow on courses were run in 1 Comm Z Postal Unit at Townsville with instructors who had experience in field post offices in Vietnam, with assistance from PMG members inducted into the CMF for the Australian post office procedures aspects 20.

Doctrine

Instructions for supplies and transport services made their appearance very early in Australia’s history in Governor Arthur Phillip’s instructions from George III. Being made personally responsible for this activity, Governors naturally gave some directions to their Commissaries on how they wished them to discharge their duties, operate their accounts and conduct their activities. Commissary John Palmer found it necessary to protest in 1792 that Acting Governor Francis Grose’s instructions were more appropriate to the duties of a purser than a commissary. Governor Philip King was proud to announce in 1802 that he had produced the first proper written instructions, the earlier ones being verbal or orders of the day; in this he was ignoring Governor John Hunter’s efforts a couple of years earlier 21. Whichever are chosen for first prize, they were but the forerunner of more voluminous writings as the colonial bureaucracy developed, both as an agent of the imperial Treasury and later separately as the Colonial Commissariats. There was a notable exception to this when Queensland Chief Storekeeper Hassell wrote to the Colonial Secretary on assuming appointment, asking for instructions on how to conduct his business. The Colonial Secretary either absent-mindedly or more probably suggestively minuted the file to ‘Chief Storekeeper – for instructions on operation of Government Stores’. Hassall took the hint and was silent thereafter 22.

Establishment of colonial military commissariat and transport corps merely provided uniformed agents of the Commissariats, but they quickly adopted military ways of doing things in the field. The Victorian Ordnance, Commissariat and Transport Corps adopted the current UK Commissariat and Transport publications. NSW also adopted British Army manuals such as Supply Handbook for the Army Service Corps 1895 and Army Service Corps Supply Officers Handbook 1899, a precedent which was formalised in Australia’s acceptance of the 1909 Imperial Defence Conference proposal to ‘adopt, as far as possible, Field Service Regulations and Training Manuals issued to the Home Regular Army as the basis for organisation, administration and training’ 23. In pursuit of this, Assistant Adjutant General Colonel J.C. Hoad’s report on his visit to the United Kingdom for the Conference contained the appropriate manuals for this standardisation, garnered from the schools which he had investigated. The ASC Training Establishment at Aldershot identified relevant publications to include Regulations for Supply, Transport and Barracks Services, Army Service Corps Training, Army Service Corps Drills and Exercises, Army Service Corps Standing Orders, Field Service Manual for the Army Service Corps, and Regulations for Supply of an Army in the Field and Organisation of the Lines of Communication 24. These and earlier publications already in use were incorporated in AASC training syllabuses, as exemplified in Military Order 130/1902 above.

Thereafter, in war it was generally convenient and appropriate to use British manuals, in peace it was hardly worth producing Australian manuals for a comparatively small audience when such supplements as précis could remedy any local gaps and modifications. Training publications from UK were consistent items in the annual budgets of both the Colonial and Australian Military Forces. Similarly, with the advent of training films as a major training medium, War Office Army Kinema Corporation productions were generally first rate or at worst acceptable. Some basic procedural publications such as Regulations for Supply, Transport and Barrack Services 1905 and later a series of Instructions for Supplies and Transport Services, Standing Orders for Drivers of Mechanical Vehicles and Standing Orders for Vehicle Operation and Maintenance (later Servicing), were produced in Australia, and during and after World War 2 a long series on supplies ranging from storage through breadmaking to rodent control. But it was not until 1970 that the present author wrote the first doctrinal publication on a chance availability between postings: RAASC Training Pamphlet No 30 Road Transport Operations. With this reliance on British organisation and manuals, doctrinal development in the AASC-RAASC was less than active.

The initial doctrine of the Australian Commonwealth Military Forces was that of local defence of vital populated areas by a local garrison, supported logistically by garrison details, with mobile brigades having integral supply (later renamed transport and supply) columns, supported by supply and ammunition columns. Transport was at first classified 25, after the reformed revamped Boer War model, as:

First Line Unit transport and brigade columns Second Line Supply and ammunition columns General Transport Other groups of surplus transport, from whatever source, forward of railhead

This was changed in 1912 26, but not implemented immediately in Australia, to:

First Line Unit weapons, ammunition, cooking, water and casualty carriers Second Line AASC divisional train with unit baggage, one day forage and rations plus one day non-perishable rations Third Line Reserve columns, motorised supply columns and ammunition parks Fourth Line Motor transport convoys, rail and water transport

That system applied in World War 1. Although there was some restructuring of supplies and transport units in each group, the system had not changed noticeably by the earlier part of World War 2 except for the replacement of the artillery-operated ammunition columns and siege parks which were displaced by the AASC parks and companies. The significant and permanent structural change to emerge from the war, which was accepted from the RASC in 1942, was that of the ‘brick’ system of building up AASC organisations from a shopping list of specialised platoons, grouped under standard general company and column headquarters according to local need. The lines of support then stood at 27:

First Line Unit transport and holdings Second Line Divisional transport with usually two days stocks on wheels Third Line Communication Zone transport and stocks Fourth Line Base transport and stocks

When Australian forces began operations in the South West Pacific, independently and in cooperation with United States forces, quite different and irregular conditions produced a variety of support systems tailored to the circumstances. All conceivable means of road, pack, porter, water and air transport were employed, special supplies and POL stocking and distribution procedures evolving to meet a wide variety of circumstances and, with often dispersed units and formations, the lines blurred. However the basic definition remained and continued through the post-war era without change, although as happened earlier the types and designations of units did alter.

By the end of World War 2 the Australian Army, and the AASC, were as well adapted to their regional environment as any other army. However a decision in 1951 to follow primary British strategic interests redirected tactical and administrative doctrine away from the Asia-Pacific area back to potential European and Middle East battlefields, and the consequent acceptance of British doctrine and organisations in toto. The Australian General Staff reproduced massive tables of organisation changed from their original only by the occasional insertion of the word Australian or letter A. As a consequence Australian officers spent fruitless hours on course and promotion examinations learning the details of such diverse creatures as the Divisional Regiment RAAC and Fast Launch Flotilla RAASC, which were mere figments of imagination in any real context. The real loss was the rundown in knowledge and thought, as experienced wartime officers and NCOs phased out and their successors learnt not from them and their experience of reality, but from the fictitious paper empires of an alien military environment.

An eleventh hour decision in 1955 to take heed of Australia’s own regional environment and a later commitment to the defence of Thailand under SEATO auspices rescued some vestiges of Australian experience while there were a few left who were able to pass it on. Techniques were resurrected and kept alive at the RAASC School – the benefit of a seat of learning, in 1 Coy RAASC (inf div tpt) as part of the ready brigade group formed in 1957 at Holsworthy, and in some CMF units where knowledge remained or was revived. Unfortunately those efforts were largely quarantined by a pseudo-local initiative which attempted to derive a ‘pentropic’ division from the US ‘pentomic’ division developed for the European nuclear battlefield. This aberration was discredited and discarded quickly enough, and would have caused little enough harm if it had not been accompanied by the Mackay Committee which presided over an emasculation of the logistics order of battle, dismissing much of the carefully thought out array and balance of units – Regular, CMF, Supplementary Reserve and Mobilisation – which encapsulated past experience of what it took to support a substantial force both in the field and in the home base. The transport, supplies, POL and ancillary structure shrunk on paper and in fact, re-enacting to a degree, but fortunately not entirely, the earlier periods of peacetime concentration on CMF divisions without the commensurate CMF lines of communication structure 28.

This setback was compounded by the succeeding concept of operations and logistic support, designed on the basis of air support 29. Under this aberration, where everything had to be air-transportable, the artillery regiments with 2½ ton trucks had a higher lift capacity than the RAASC companies in support, which were largely equipped with Landrovers and trailers. While the introduction of a light scales component was a perfectly valid adaption to national strategic requirements, the problem with this and the previous home-grown deviations was that they were not just specialist force components for a particular contingency within an overall standard force. Rather they were total restructurings of the Army field force, doctrine, organisation and equipment policies from top to bottom in which many specialist communication zone units virtually disappeared from the order of battle. By 1973 they had not been restored, and their function and the inescapable need for them had fallen from memory. Compounding this was the Vietnam experience which did not stop at teaching lessons of very specialised and sometimes less than responsible logistics; reliance on the immense American support infrastructure masked the lack of capability of the residual Australian logistics system. The RAASC consequently retained negligible doctrinal baggage to pass on to its successors.

While it was obvious that Australia could not continue to follow British doctrine which was designed for the nuclear battlefield, its 1960s attempts at developing its own doctrine were not memorable experiences, and when allied to the distortions and dependency learnt from Vietnam, left the Army at large and the RAASC in particular without either effective doctrine or broad practical experience. Termination of the Vietnam commitment and government withdrawal from a forward defence posture both exposed the gap in doctrine and general experience, and opened the way for recovery of a rational and broad based approach within which specialised techniques could be retained, but the upcoming termination of the RAASC paralysed development. Reconstructing and reinstituting workable doctrine for supplies and transport relevant to the Army’s future needs lay ahead for RAASC’s successors, and that was by no means a straightforward path where the sinews of war had been separated from their means of delivery.

Footnotes

1. See Chapters 7, 8 and notes.

2. MO 24/1904; CPP 1906 vol II Finn Report for 1906, p16; Finn Report for part 1906, p12; 1911 vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p10.

3. MO 24/1904; CPP 1903 vol II Hutton Report, p10.

4. CPP 1911 vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p5, 22; 1912 vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p17; 1913 vol II Kirkpatrick Report, p20; Holdsworth 'AASC' ASC Quarterly April 1907, p161.

7. Scott vol XI, p213, 227; AWM 183NN; Bean vol II, p410-1; vol III, pI63-4; AWM 224 MSS 210, p11; AWM 26 721/58.

8. AWM 224 MSS 210, p11-18, 20; Bean vol III, p166, 169, 177-8; Crew RASC, p 137; AWM 224 MSS 212.

9. AAO 452/1924; 510/1926, 398/1927, 242/1928; CPP 1926-28 vol II Chauvel Report May 1926, p13; May 1927, p17-8.

10. AAO 358/28; DMOVT-A Files History of the AASC During the Second World War 1939-1945 Chapter 26.

11. CPP 1926-28 vol II Chauvel Report May 1926, p13; May 1927, p17; May 1928, Appendix B; Army List 1929, 1930; AA B1535 763/2/2; AAO 401/1928.

12. AA B1535 869/4/70; AAO 53/1934; DMOVT-A Files AHQ AASC School, Osborne House Geelong.

13. DMOVT-A Files AHQ AASC School, Osborne House Geelong; History of the AASC Chapter 26.

14. 'The Military Forces of Victoria' Chapter 9; Par Oneri March 1940; Army ORBAT December 1941, October 1942-June 1943; '1st Australian Mobile School of Mechanisation AASC' (Wyatt paper).

15. History of the AASC Chapter 26; AWM 52 10/43/16 August-September 1945.

16. RAASC Quarterly Bulletin No 1 1951, No 10 1953, No 11 1953;'The RAASC Centre’ RAASC Digest 1967, p30; DMOVT-A Files DST Brief 20 October 1967.

17. RAASC Quarterly Bulletin 1952, 1953; 'Introduction of Pacific Islanders into RAASC units in PNG' RAASC Digest 1963; interview C.R. Cox.

18. CPP 1925 vol II Chauvel Report, p18; 1926-28 vol II Chauvel Report May 28, Appendix B; AAO 19/1937, 174/1938, 153/1938.

19. CPP 1925 vol II Chauvel Report, p18; 1926-28 vol II Chauvel Report to May 28, p22.

20. RAASC Digest 1967, p24; Department of Defence (Army Office) A1300/1/20 dated 26 May 1983.

21. HRA I.1 Instructions, p10; I.2 Palmer to Hunter 29 August 1796, p651; King to Portland 18 September 1802 Enclosure 11, p632-6; King to Secretaries of the Treasury 28 September 1802, p675; I.2 Portland to Hunter 3 December 1798, Enclosure 11, p632-6.

22. Queensland State Archives COL/R4 3839 of 15 October 1869.

23. Victoria Government Gazette 4 October 1889, p3308; Browne and Anthony 'NSW ASC', p45; V&P NSW LA 1896 vol IV Hutton Report, p8.

24. CPP 1907-8 vol II Military Board Report, p8; 1909 vol II Imperial Defence Conference, p34; Hoad Report, p62.

25. Pakenham War in South Africa, p418; CPP 1904 vol II Hutton Report, p19.

27. Administration in the Division 1956.

28. The one sound output from the 1960s, whose content was dated by organisational change but not principles and procedural guidelines, was The Pentropic Division in Battle – Administration replacing the brief and limited British Administration in the Division. The author of the former was Lt Col S.R. Birch whose wide practical experience from being a platoon commander of A Inf Coy AASC at Tobruk to Chief Instructor of the RAASC School led to a practical and comprehensive publication which became the model for later versions.