Chapter 16

Containment Wars

Korea

The beginnings of the proxy wars, sponsored by the totalitarian regimes of the USSR and newly-established Chinese Peoples Republic set on expanding their hegemonies, opened when North Korean forces crossed the partition line of the 38th Parallel into South Korea on 23 August 1950. Australia committed first the RAAF, then Third Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment to the United Nations forces rushed to the defence of South Korea after a Soviet walkout in the Security Council had fortuitously removed its veto of the action.

To facilitate logistic support a small Australian Force in Korea Maintenance Area (AUSTFIKMA) was set up by Capt W.R. Barrett at Pusan in which he, a five man supply detachment headed by Sgt C.N. Govett and the transport element of AUSTFIKMA Field Ambulance Section represented the RAASC. The supply detachment was not there to provide full support which was undertaken by the US Army, rather to supply special Australian calibres of ammunition, canteen supplies, replacement items for those US ration components not attuned to Australian tastes, and to expedite and escort the forward movement of freight consigned to the front through the congested transportation system managed by the US Army – the first rail move of a box car of stores and flat car of vehicles to north of Seoul took seven days. Subsequently as the front stabilised around the 38th Parallel and the lines of communication became established, the operative element of AUSTFIKMA was dispersed in January 1951, as a more routine system for supporting Commonwealth forces in Korea from the base in Japan was developed 1.

British Commonwealth Force in Korea (BCFK) grew by March 1952 from the initial brigade group into 1st Commonwealth Division with an Australian component of two battalions plus small elements in the Divisional and 28th Brigade headquarters and in the British Commonwealth Communication Zone organisation. Establishment in Korea of the separate supplies and transport organisation, after the early expedient of relying on the Americans, provided a base to front line system which met the specific needs of the national components; costs were rationalised under inter-governmental arrangements. The Australian base units at Kure, established to support a diminishing BCOF and until the outbreak of the Korean hostilities planned for disbandment, issued stocks to the British Communication Zone units for distribution to Australian, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Indian and on occasion Turkish and other units. This arrangement kept in place the already smoothly running arrangements of 41 ASD, but as this effort in Japan was counted as Australia's AASC contribution, the divisional and communication zone units in Korea were provided by the United Kingdom and New Zealand 2.

A small element of representation and experience was, however, gained by attachment of individuals to the units in theatre, but the strongest numerical intrusion by RAASC into the peninsula was a 58 vehicle convoy led by Maj B.J. McNevin from Kure on 8 December 1950 carrying Christmas fare forward to the force which was blocking the Chinese advance at Uijonbu, just north of Seoul. The RAASC contribution was also augmented by the secondment of officers to infantry units. To meet the demand for infantry junior commanders after the second battalion was committed Lt R.R. Harding joined 1 RAR in 1951, Lt R.C. Wilson was allotted to 2 RAR while Lt D.C.J. Deighton was seconded to 3 RAR in 1953 after the truce. In addition from early 1953 RAASC was required to provide 21 percent of the infantry reinforcements and replacements, filling rifleman, LMG number, driver and clerical positions in the battalions, amounting to about 40 per month 3, a considerable number serving in 2 RAR and 3 RAR in the closing stage of the war.

Resistance to the Japanese occupation of Malaya during World War II was substantially organised by the Communist Party of Malaya, which carried on the struggle afterwards against returning British rule from the base of a large rural Chinese population which the Japanese had resettled in the countryside to grow food for their army. Australia provided initial RAAF assistance from 1950, but with a foreign policy reappraisal which turned from the Middle East back to South East Asia as the primary area of strategic interest, it was decided in 1955 to participate more seriously in the counter-revolutionary effort through an infantry battalion and supporting elements.

The first contingent of RAASC members accompanying 2 RAR arrived on MV Georgic in November 1955, joining 3 Coy RASC at Ipoh. This contingent included a component for the company headquarters, a transport platoon and a relief driver increment. Capt A.E. Goodall joined HQ 3 Coy as second in command but, as the UK had already established a full headquarters staff, the others were allotted to the transport platoon for employment until vacancies should occur. 126 Tpt Pl was commanded by Lt A.T. Hall who, with the spare headquarters members and relief driver increment, had a command of over a hundred soldiers. The relief driver increment was allotted to bring manning up to the two drivers per vehicle necessary for prolonged operations and defensive measures. This was shown to be necessary when, in December shortly after its arrival, the unit was ambushed by terrorists 80 km south of Ipoh on a routine task to the Cameron Highlands, the first Australian troops in action, as 2/3 Res MT Coy had been fourteen years earlier against the Japanese. The convoy broke through the ambush without casualties, with the assistance of the standard escorting scout car and armoured car.

Life for the platoon continued to be varied. With its over-strength, it was obviously set to be allotted extra responsibilities. For the first six months it was tasked to provide an infantry platoon at weekends to relieve a Malayan infantry battalion in patrolling duties in the area. Apart from a variety of troop and cargo tasks, the routine run lpoh-Highlands continued and a second ambush was encountered, this time while the convoy was carrying Special Air Service members, one of the drivers Pte Williamson distinguishing himself by felling an opponent in a rugby tackle. The unit was withdrawn from Malaya at the end of the second year.

Other positions were held by RAASC members within 28th Brigade. Capt D. White was Staff Captain A on brigade headquarters and Maj L.C. Chambers commanded a rifle company of 2 RAR. And as a further part of its contribution to the Reserve other elements were also included in British units: six drivers in the transport section of 16 Fd Amb which was part of 28th Brigade; 30 clerical positions on Brigade and Force Headquarters and RASC depots; one or two officers with 55 Air Dispatch Coy and one with the HQ AASO; and an ADST on the DDST staff of Headquarters Far East Land Forces. In addition eight officers were phased into other British units through the Visitors and Observers Unit, including Lt WG.R. Fleming as a pilot with the UK Reconnaissance Flight. The State of Emergency was terminated on 30 July 1960, however RAASC members continued to occupy positions in 28th Brigade, now stationed at Terendak, others continued to serve with RASC supply depots and on Headquarters FARELF in Singapore, and two sections of 39 Air Dispatch Pl were allotted to 55 AD Coy from 1960-62 4.

Malaysia Confrontation

The actions of an ailing, erratic and opportunistic President Sukarno of Indonesia in creating external enemies to distract popular attention from a failing economy and living standards led to his denunciation of the State of Malaysia on its formation in September 1963, and military intervention to destabilise it. Indonesian sponsorship of an earlier attempted coup in Brunei on 8 December 1962, followed by uprisings in and cross border raids into Sarawak and Sabah, and attacks on the Malay Peninsula and Singapore, kept up an ongoing silent war which saw Australian Infantry, Special Air Service and Engineer units involved in helping to suppress the incursions and promote civic action to counter the campaign 5. It was conducted as a silent war because it was decided that security force successes, and they were significant, would if published only discredit the Indonesian Army, and that Army was the major force for stability in Indonesia against the growing influence of the Communist Party. Media releases were generally made only to explain Commonwealth casualties.

In these operations, while there were no RAASC units, some members assigned to RASC units entered the operational area. Lt R.T. Willing managed to accompany HQ Army Air Support Organisation to Brunei, while Lt D.R. Woolmer, who was commanding Kemar Platoon of 55 Air Dispatch Company based at Seletar in Singapore, was deployed with his unit to Brunei two days after the outbreak of the revolt. The latter's involvement in a command position brought problems on whether Australians were permitted to be there, Australia at that stage not being officially involved. This reawakened echoes of the Suez war of 1956 when an Australian squadron commander in a British armoured regiment was withdrawn from the unit on its deployment into action, resulting in subsequent exchange officers being held in supernumerary positions. This had eventually been overcome on the assurance that such withdrawals would not reoccur, yet Australian Army Force FARELF requested Woolmer's withdrawal after it was committed to operations. Faced with a repeat of the earlier repercussions, authority was given for him to remain for the period of deployment, and he returned for two subsequent tours of operations of two and three months at Brunei and Labuan during 1963 6.

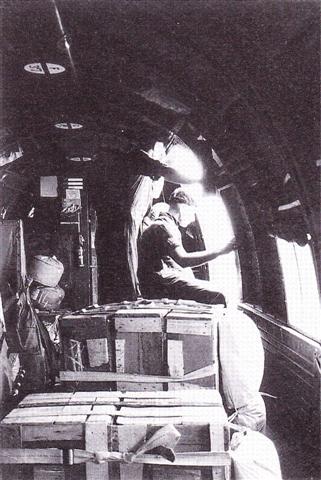

Operations in North Borneo were supported on a shoestring, in an example of how to avoid adding logistics overheads which come to feed on themselves and demand their own infrastructure and overheads. A signal demand system allowed quick response from the Singapore base, which allowed minimisation of forward stocks and units, including regular air supply of isolated posts and bases; RAASC participation in this with 55 AD Coy continued with Lts J.D. O'Neill and L.P. Miller, the two air dispatch sections having unfortunately been withdrawn to Australia a few months before the outbreak of hostilities. The campaign's spartan operational logistic support arrangements are especially deserving of study as a comparison with both the logistics infrastructure which grew up in the subsequent commitment in South Vietnam, and contemporary and subsequent logistics components included in operational contingency plans and training exercises.

Vietnam

Entry of North Vietnam's regular army into the guerrilla warfare in South Vietnam escalated involvement by the US Army from advisers to fighting units. Australia, eager to cement US resolution in arresting the potential fall of the South East Asian dominoes and also wishing to be seen as an active ally and participant, contributed a battalion group, including the Australian Logistic Support Company comprising a headquarters commanded by Maj R.B. MacDonald, a transport platoon, supplies, ammunition, petroleum and air dispatch elements plus medical, ordnance and maintenance detachments. This 1 RAR Group was incorporated into 173rd US Airborne Brigade located at Bien Hoa airfield, where the logistics company set up its base, drawing its supplies, fuel and ammunition from US sources.

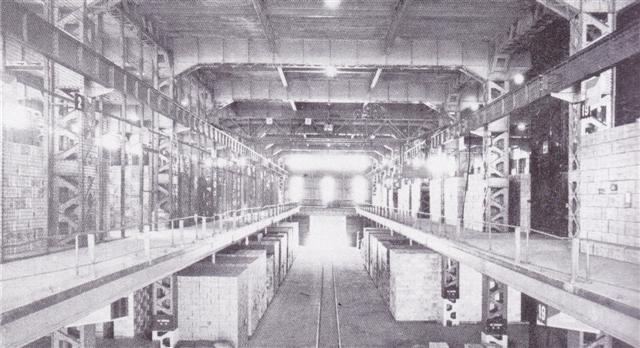

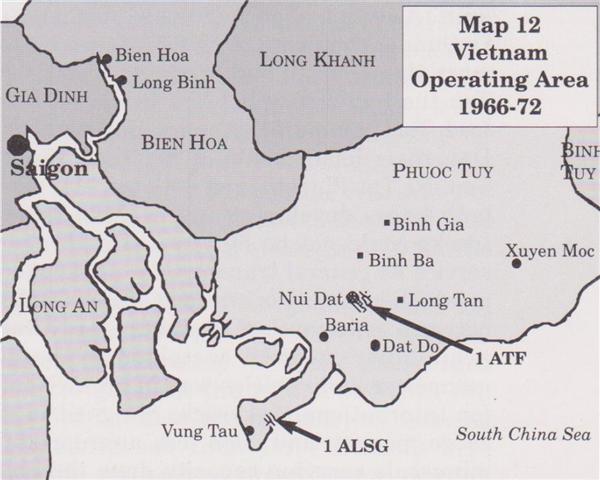

Escalation of Australia's commitment to a two-battalion task force in April 1966 resulted in 1st Australian Task Force being allotted responsibility for Phuoc Tuy Province and its resident 5th Viet Cong Division manned largely by North Vietnamese. The Task Force set up an operational base at a Nui Dat, while 1st Australian Logistic Support Group established itself at the port of Vung Tau. The first foolishness lay in the planning for this Group, which was done at Army Headquarters in Canberra: its composition was determined by first satisfying the needs of the fighting elements, then allocating to logistics units the leftover manpower within the specified numerical ceiling. The result was a logistic support element woefully inadequate for the dual task of both establishing a base from scratch and simultaneously supporting operations. This was belatedly recognised, and a year later a considerable augmentation arrived, at a time when the teething difficulties were largely overcome, but these increasingly excess troops remained until overall force reductions began in late 1970.

The other dubious decision lay in establishing a garrison area at Nui Dat with its own administrative component which in many ways competed with the 1st Logistic Support Group units and vice versa. While at the outset this was minimal, the base being basic, and 1 ALSG providing most of the support, the growing infrastructure at Nui Dat and establishment of duplicate logistics units there, created substantial unnecessary overheads. When resources were short, this diluted those available in either area; when they were plentiful, it allowed for two systems to grow, uninhibited by realistic resource limitations. Poor lessons were learned by the generation of officers and NCOs who passed through, witnessed or were taught from this unrealistic system.

From the beginning it was established that mainstream support would be provided by US forces on a repayment system. The Australian logistics element was there to provide the interface and field distribution service, plus handle a limited range of specialised Australian-sourced items. The later oversufficiency of logistics units permitted the provision of increasing services and supply, leading progressively to extensive Australian-sourcing of items available from the American system. While much of this unnecessary demand was in the field of Ordnance stores, the RAASC units found that they also had the resources to provide a rolls royce service which avoided the periodic scarcity which the US system accepted as the inevitable result of peaks of supply and demand. It also allowed growth of a routine of leisurely supply action and transport operation, only occasionally interspersed with short periods of realistic activity in which performance was not enhanced through regular practice of tight operation. Behind the finite capacity of the RAASC resources lay a mammoth US Army logistics system, augmented by the resources of a civil contractor, the Alaska Barge and Transport Company whose equipment and efforts in wharf clearance masked the long-standing refusal to equip the 1 ALSG transport units with high capacity load carriers, which would also have drastically reduced the numbers of men and vehicles required for deliveries to Nui Dat.

The initial RAASC deployment group was 1 Coy containing 1 and 87 Tpt Pls, 21 Sup Pl, Det 8 Pet Pl, Det 1 Div ST Wksp, plus a detachment of 1 Div Postal Unit newly raised to meet this commitment; each of the platoons was less one section to meet the numerical ceiling 7. The Company moved in HMAS Sydney and was unloaded into the sandhills of Vung Tau to make itself an operating base while supporting both 1st Task Force operating out of Nui Dat and 1st Logistic Support Group itself. The task was many faceted. First was the support of 1st Task Force operations in the Province; second, support within the Task Force base at Nui Dat; third, support of the Logistic Support Group base; fourth, the periodic six-weekly clearance of the resupply ship Jeparit; fifth, the opening task of assisting in developing both Task Force and 1st Logistic Support Group bases; sixth in administering HQ 1 ALSG and other small units which were not self sufficient; and finally developing its own living and operating facilities within the base area which was 'during the wet season under water and during the dry ... under sand'. The well learnt lesson of the past of putting in temporary additional units to cover the development period was lost in the leftover-manpower ceiling syndrome.

Map 12: Vietnam Operating Area 1966-72

The net effect was the old solution of running men and machines to their limit. A section of each of the supply and transport platoons was located at Nui Dat under command of Lt P.K. Roper for routine local distribution and tasking, most significantly bulk cartage of water from water points to units. At Vung Tau the half strength 1 Tpt Pl opened the day with two maintenance runs of food, fuel, ammunition, engineer, canteens and general stores 30 km to Nui Dat, then deployments of the Task Force, followed by commitments at Vung Tau. 87 Tpt Pl, equipped with tippers, was committed to the engineer effort at both bases developing internal roads and unit areas, but the demands for trucks could not be met by 1 Tpt Pl alone, so the tippers were pressed into service as general transport for peak loadings. It was a seven day a week task in which company operations officer Capt D.B. Ferguson had to keep a balance between maintaining maximum daily vehicle availability and ensuring that availability could be sustained in the long run. The output of the limited manpower and vehicles was in no way helped by the nature of the latter – 2½ ton International 4x4 trucks designed as general purpose all arms vehicles, not cargo movers; and even less appropriate commercial 2½ ton tippers, whose minuscule carrying capacity drew the epithet 'teaspoons'. For the other part, Capt P.J.F. Tuckett's 21 Sup Pl had a mammoth part in trying to acquire a balance of commodities from a US Quartermaster Corps which dealt in bulk and worked on the feast or famine system. Another lesson learnt brought with the next year's reinforcement not only 85 Tpt Pl but also a detachment of 8 Pet Pl to handle the major fuel usage of armoured and aviation units which an army organised around the jerrican and 44 gallon drum could not cope with 8.

After this critical year 5 Coy relieved 1 Coy in the only unit changeover, thereafter the units remained and the members were replaced on a trickle system. The unit had been re-raised, after 1 Coy's departure, to be ready to relieve it in Vietnam the following year; when it took over it was in a considerably better position than its predecessor on two counts: the ground rules and ground work had been laid, and a fuller complement of strengths and specialist units was available This was further amplified with the progressive replacement of the 2½ ton tippers with International 5 tonners from May 1967, and from October the phase in of 5 ton cargo trucks. The unit comprised 2, 85 and Det 86 Tpt Pls, 25 Sup Pl, Det 8 Pet Pl, Det 176 AD Coy and Det 1 Div ST wksp, with Det 30 Tml Sqn RAE also under command. The first OC of 5 Coy, Maj N.W.J. McViIIy began with a slogan SAIF (stay alive in five) ensuring that adequate training and operating procedures were used to minimise risks from both military and industrial hazards, a policy followed by his successors which paid off handsomely in a minimal casualty rate. The new unit, with extended resources and relieved of extra-unit administrative burdens by the raising of an ALSG headquarters company, was able to complete the normalisation of operating procedures and meet the testing demands of acting as both brigade company and base area company. The usual forward detachment at Nui Dat was augmented with an element of 8 Pet Pl to handle the bulk refuelling of helicopters and vehicles, and a crew from 176 AD Coy 9.

As a result of the difficulties of servicing the two expanding bases it was decided to hive off part of the resources into a second company dedicated to 1st Task Force and its base, with the additional task of commanding other corps’ logistics units as a HQ Task Force Maintenance Area. HQ 26 Coy established itself at Nui Dat under Maj G.J. Christopherson in December 1967 with under command 85 Tpt Pl and detachments of 25 and 52 Sup Pls, 9 Pet Pl, 176 AD Coy and 1 Div ST Wksp. As a result of this redistribution, 5 Coy now contained 2 and 86 Tpt Pls plus a section of 86, 25 and 52 Sup Pls, and detachments of 8 Pet Pl, 176 AD Coy, 1 Div ST Wksp and 30 Tml Sqn. Organisation and bedding in of this separation masked the oversupply of effort for a period, but when the system and bases had been established, the growing effectiveness of 26 Coy exposed the limited and spasmodic work available for a 5 Coy now in a settled environment, with a forward distribution company and considerably greater resources than either 1 Coy or itself had in the frenetic earlier days. The politics of not changing the order of battle of the Force, until the rundown begun in 1971, precluded an earlier significant reduction, however the OC of 26 Coy was able to find employment for all of Det 176 AD Coy within the Task Force from mid-1969, and 5 Coy was careful to ensure that 26 Coy was adequately augmented for peak activities. It worked because it was made to do so, not because it was the most effective arrangement 10.

Det 1 Comm Z Postal Unit operated Field Post Offices at the three major areas: AFPO 1 at Saigon, AFPO 3 at Vung Tau and AFPO 4 at Nui Dat. AFPO 5 serving the Canberra bomber squadron at Phan Rang was operated by RAAF, and with lack of supervision by the Squadron, and without that of the headquarters of the Postal Unit, was a weak link in an otherwise super-efficient chain. This system by 1969, with the cooperation of the PMG postal system at home, was producing better postal times from Australia to Vietnam than inter -suburban deliveries in Sydney. But it was not possible to please everyone, as the faster the delivery system became, the more individual complaints were received for such exotic reasons as preference for a bundle of letters at a time rather than daily single ones. This speed was achieved by using US Rest and Recuperation flights to and from Australia, but US staffs were incredulous at the desire of otherwise rational Australians to make extra effort for fast regular deliveries of mail, considering a weekly delivery adequate and twice-weekly a superior service.

A significant area of participation was in the headquarters staffs. It was disappointing in the broader logistics field that the DAQMG of 1st Task Force fell to a succession of armoured and signals officers of no observable logistics talent or enthusiasm, instead passivity and passing negative decisions up for the Force Headquarters to make; a notable change took place with a temporary occupant Maj B.C. Barrett RAAC, whose strength was carried on by his successor Maj P.W. Blyth, the only RAASC officer to hold the position, and even this was short lived. Problems with the Task Force operations staff led Brig S.P. Weir to take on a known winner and transfer him to Operations Officer, to the consternation of the 'arms' fraternity. Otherwise, leadership of the logistics staff tended to fall to the strongest of the captains which sometimes was the RAASC officer, one in particular being Capt D.W. Ford. Similarly at 1st Logistic Support Group, Lt Col L.C. Chambers was the only RAASC officer to command, and the logistics operations staff were infantry, artillery and armoured officers. The position of DAQMG controlling administration did however fall to such capable RAASC operators as Maj R.J. Darlington.

An area of consistent success was in Headquarters Australian Force Vietnam at Saigon where, apart from an initial short unsuccessful period with an infantry officer, the position of DAQMG was held successfully by RAASC officers: Majors N.J. McGuire, D.C.J. Deighton and N.R. Lindsay; it was upgraded to AQMG during the latter's term, and after a short term incumbent the tradition was carried on by Lt Cols K.L. McPherson and A.T. Hall. The essential backstop of Staff Captain Q was also held by several RAASC officers, the most significant Capt D.J. McLachlan. A position of DADST also existed, initially on Headquarters 1st Logistic Support Group, then transferred to HQ Australian Force Vietnam when practicalities of dealing with the US system made it obvious that that was the only effective place for all the Service staffs, rather than overgoverning the Service units in Vung Tau; the incumbents were Majs R.B. Harland, V.C.Y. Smith, J.P. Hunter, L.A. Power and A.J. Corboy. Many other Corps members occupied non-corps positions: in the Civil Affairs and Amenities Units; as clerks on the Force, Logistic Support Group and Task Force Headquarters; in the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam, beginning with one officer in 1963, building up to four warrant officers and three sergeants in 1968, to three officers and one sergeant in 1971; and two short term AASC members from the 1940 RMC armoured specialists, Brigs S.C. Graham and C.M.I. Pearson, commanded 1st Task Force.

Activities of the units were as multifaceted as has always been the case with the AASC. In the initial Logistic Company they were comparatively straightforward, with all but a few unavoidably Australian-sourced items coming directly from the US system and issued to the battalion group units at the Bien Hoa base or in the field. In the expanded situation, 1 Coy, and then 5 Coy, was located near a US supply complex at Vung Tau, from which they drew the force requirements, delivered them to Nui Dat and distributed them within 1st Logistic Support Group. Again, apart from Australian field ration packs and special lubricants, the uniqueness of which was also doubtful, there were few products which needed to be imported from Australia. But in a questionable move, stocks of US-supplied commodities were accumulated in the company area to insulate against the US feast or famine situation, at a cost of men and storage facilities, though this was simply parallel to the other areas of overservicing throughout the force. Daily convoys delivered commodities to Nui Dat where selective overstocking once again occurred after 26 Coy was established. The intensity of operations for the Vung Tau-based units after the setting up difficulties was low, other than at times when large operational deployments and the unloading of Jeparit and HMAS Sydney caused temporary flurries. From late 1970 in the run down phase before the withdrawal, in line with the reducing combat commitment, the platoons were progressively withdrawn and semi-trailers were introduced, rationalising the resupply effort, coping better with wharf tasks, and allowing reduced numbers of men and vehicles to continue to cope, which might have happened with advantage two years before. 26 Coy closed in June 1971, the last elements of 5 Coy leaving in April 1972.

Operations of 1st Task Force were essentially harassment of the enemy forces in Phuoc Tuy Province, aimed at defeating the main force regiments and driving them out, then weeding out their local force units from the jungle and amongst the populace. The technique was centred on establishing fire support bases containing artillery and often logistic support elements in an area of operations and operating outwards from there. These bases typically contained transport, petroleum and air dispatch elements to service the units deployed in the operation, and were resupplied by helicopter; for larger and longer operations a forward task force maintenance area headquarters was set up in one of these bases by HQ 26 Coy to control resupply activities. During major activities Det 176 AD Coy came into its own rigging and loading heavy lift cargoes of fuel and ammunition forwarded by Chinook and Skycrane helicopters from helipads St Kilda at Vung Tau and Kangaroo at Nui Dat. The high use rate of aerial delivery equipment also required air dispatchers to be stationed at the fire support bases for its salvage and backloading, to prevent it being discarded or converted by units to other handy uses. Deployments from the Task Force base into the operational areas and their replenishment could be by road transport or air. When a major road lift was required the company at Vung Tau would provide the additional transport. Such major lifts also occurred during the annual North Vietnamese Tet and other offensives against the US Long Binh base complex, when a major part of 1st Task Force was deployed into Bien Hoa province as a protective or blocking force and both a forward task force maintenance area and forward logistic support force were established to maintain the force away from its usual support lines.

The list of operations the RAASC elements participated in marks the course of the Task Force's operations in the war: one or both companies participated in such operations as Paddington, Coburg and the Toan Thang and Capital series, where RAASC sub-units not only had their technical tasks to fulfil, but usually had their own section of perimeter to defend. In Paddington Capt R.C. Sherman's platoon of 5 Coy maintained the integrity of its perimeter, which was not so with adjacent units which were infiltrated; later operations reproduced the problems which were met without losses. Similar own-defence responsibilities at Nui Dat were added to in 1969 when 26 Coy was given part of the in-depth patrolling task, the first such patrol led by Capt J.C. Snell 11. RAASC units' duties were supply and transport but, in an environment without defined front lines, protective measures in place and on the move were a continuing priority. One of the best talismans against attack is the preference of any enemy for easy targets, and by maintaining an obvious readiness to respond, the companies did not attract such attention, resulting in the very low battle casualties sustained.

Problems of resources not matching tasks had the same results for the members of the Corps which has existed since its inception, and indeed with its predecessors. When the demand for support was there, they worked themselves to a standstill, then continued on. And while with many other corps there was a finite end to operations then rest, reassessment and restart, the task of the RAASC was a continuing seven day a week support one, with the accompanying need to look after their equipment maintenance and domestic economy after the main tasks were done. In later stages in the underemployed units in Vietnam there was an unfortunate oversufficiency of time with plenty of training and keep-them-busy activity, with resultant morale problems. But for the earlier stages, the rundown period and for those deployed in the field, it was a constant round of meeting supply and transport tasks and looking after their own administration and security. The RAASC had much to be satisfied about during this extended war in its effective support of the force and its operations. There were a few weak links, the resources often did not match the task one way or another and politics hampered appropriate readjustments, but the RAASC soldier, Regular and National Serviceman alike, had kept the Corps' traditional responsiveness well up to standard. But a particular regret lay in the method of operation of the trickle relief system: only three RAASC companies saw operational service in over six years. It would have been quite simple to have exchanged unit titles, as well as members, annually with units in Australia and so ensured that eight other companies had further operational service added to their already distinguished records.

Other Fields

Between declared wars, the Australian Army has had its members committed to a variety of operational areas, arising either from seconding or exchanging soldiers with the British or American Armies or through the secondment of members to United Nations peacekeeping forces. Although no AASC units have been involved, individual members have taken their share of the opportunities and obligations. After return from Europe and the Middle East in 1919 the Army faced a long respite from active service up to World War 2. The only area where Australian servicemen were sent, as opposed to civilians who volunteered for such causes as the Spanish Civil War, was to the Northwest Frontier of India where the tribesmen had always been ready to take on all comers as they undertook their traditional raids on the plainsmen. The purpose of the Australian commitment was to provide permanent servicemen with some operational experience, in an imperial setting which would not compromise national foreign relations. Also, militia members Capt D.P. Young, OC of 23 Coy was seconded in 1912-13 and 2Lt A. Matheson of 22 Coy in 1913-14 for AASC training. Included in the post war period was Lt E.M. Dollery MC who was attached to Indian ASC transport units in 1926-27. This link with the Indian Army was reciprocated in 1944 when Australian officers were attached to recently raised divisions in the Burma campaign to pass on the knowledge which they had gained in New Guinea: Capt C.M. McCartney was sent as an instructor to the RIASC.

The horizon widened in the aftermath of World War 2 when the United Nations attempted to avoid the failures of the League of Nations' passive policy by establishing observer and peacekeeping forces to supervise settlements of conflicts. Maj J. Williams served with the UN Truce Supervision Organisation Palestine 1964-67 and Capt L.W. Daniels served two tours as UN Military Observer Kashmir 1964-66 and 1968-70 12. After the end of the war in Vietnam the Australian Army had entered an unprecedentedly long period of military inactivity, in itself a national blessing, but it also provided the potential for Australia to participate more widely in United Nations peace efforts. As the Australian Army was regarded internationally as logistically sophisticated, and Canada had tired of filling this role for UN peacekeeping forces, Australia began to be invited to take on that mantle. Unfortunately the Army's ruling establishment preferred to send infantry, which was not required by the UN, and opportunities were lost for RAASC's successors to participate in such productive and humanitarian deployments.

Footnotes

1. Govett C.N. 'Korea Diary'; AWM 52 10/10/37 September 1950-January 1951.

2. O'Neill R.J. Australia in the Korean War 1950-55 vol 2, p88, 238; AWM 52 10/10/37 December 1950.

3. Interview R.R. Harding; Army List 1966; Smith N.C. Home by Christmas p140, 167; RAASC Quarterly Bulletin No 9 1953.

4. Smith N.C. Mostly Unsung – Australia and the Commonwealth in the Malaya Emergency 1948-6, p2l-5; interview A.T. Hall; RAASC Quarterly Liaison Letter No 8 1958.

5. Smith Mostly Unsung Appendix 8.

6. Interview D.R. Woolmer, J.D. O'Neill; Smith Mostly Unsung p30-1.

7. '1 Coy RAASC in South Vietnam' RAASC Digest 1967, p55.

8. Interview D.B. Ferguson; '1 Coy' RAASC Digest 1967, p55f.

9. Fegan B.R. 'The Saif Story', RAASC Digest 1968, p58f; DMOVT-A Files DST Visit to South Vietnam 1967; Brief on 5 Coy RAASC Part 3.

10. Christopherson G.J. 'Operations of 26 Coy RAASC - 1ATF - Nui Dat December 1967 November 1968; RAASC Digest 1969, p48f; Douglas P.M. ‘The SAIF Story Continued' RAASC Digest 1969, p55f DMOVT-A Files DADST AFV Reports 1967-71; Kirkland F. ed. Sometimes Forgotten exhibits a real problem in recent publishers of the postwar period, with shallow research and poor checking, in which, for example, the RAASC unit details are full of errors as well as half being omitted altogether; postal is shown under Engineers and other places in duplication; and the rolls are error-ridden. One can only speculate on the nature of such publications being targeted towards the medal collector fraternity which has intruded so substantially into the military history field.

11. 'SAIF', '26 Coy', 'SAIF Continued' RAASC Digest 1967, 1968, 1969.