Chapter 15

World War 2

The Australian Base

The beginnings of World War 2 were not dissimilar in prospect to those of the Great War. On 3 September 1939 Australia and the other self governing nations of the British Empire followed the United Kingdom into a war in Europe, with the usual spillover to the Middle East and maritime threats on the high seas. While Japan remained a worrying future threat in the region, Australia's commitment was once again to provide combat forces to operate overseas within the framework of and supported by the British forces, and to act as a source of strategic materials, while the militia divisions trained and provided for home security. This role was accepted and followed for most of the first two years of the war until the deteriorating prospects in the Pacific forced a belated upgrading of both operational forces and the logistics infrastructure in the home base.

An immediate effect of the Australian Government's acceptance that the United Kingdom's declaration of war on Germany was also operative for Australia was the call up of the militia to undergo one month training, half at a time, and an offer of a mirror of the earlier war's 20,000-man expeditionary force. The next impact was to find the equipment for the force, which meant finally biting the bullet on motorisation. In default of a substantial purchase of trucks for the Army in the pre-war warning period which unmasked Treasurer Hasluck's claim that 'Defence can have any money that it wants', a plan to impress vehicles existed, but was implemented as voluntary hiring rather than acquisition after the declaration. However while the civil community was effectively motorised, in contrast to the horsed Army of 1939, the types, makes, ages, condition and repair parts situation of this potential pool made it a very weak reed on which to not only equip the new 6th Division but also transform the remaining seven divisions and meet the Army's other expanded operating requirements 1.

Implementation of the hiring plan devolved largely on the AASC, as had the initial horse and wagon procurement of 1914. In each State, regional sections of AASC Vehicle Collection Centres assessed and accepted vehicles suitable for military use and forwarded them to Vehicle Reception Depots for repainting, reconditioning and issue to units. These commercial acquisitions did little to meet the need for field-performance vehicles and even less for the 3,000 odd needed for the initial AIF division. Not that there was unanimity on the need for these vehicles as the self confessed experts in Department of Treasury argued that procurement for the AIF be suspended until it had been determined if it was necessary for motor transport to accompany the force overseas. Some sanity prevailed and an order for 784 trucks for 6th Division and 2,860 for the Militia was proceeded with, although both these allocations were at training scales only. Succeeding AIF divisions were equipped with vehicles overseas, while Militia vehicles additional to the training pool continued to be sourced from hiring, until impressment was substituted nearly a year after the outbreak of war. This continued for two years until responsibility was transferred from AASC to AAOC, and the VCC and VRD were disbanded 2.

The influx of recruits for both AIF and Militia required a means of recruit and technical training if the operative units themselves were not to remain as basic training units. While the latter had been acceptable enough in World War 1, when there was no home threat and the first AIF had established its own comprehensive training system overseas, Australia's now deteriorating strategic environment increasingly placed the home-based divisions in a ready field force role. AASC training units were opened, then expanded to AASC Training Depots in each of the four Commands – Northern, Eastern, Southern and Western. These were supplemented by various specialist schools for general and technical training, operating under names which varied as the home command structure changed from commands to lines of communication areas and armies. The AASC School changed name and function, regional MT schools opened and courses in vehicle maintenance, petroleum, food technology and inspection were conducted by civilian organisations 3.

Progressively an infrastructure was built up to supply and move forces firstly for the home defence plan, then as the focus switched to the Pacific theatre, to maintain the forces training for and operating in the New Guinea and Island campaigns. An early move in this was the opening of the overland supply link between the Alice Springs and Larrimah rail terminals and also a feeder route from the Mt Isa terminal. The massive increase in full time duty forces in 1942 resulted in a network of base supply and petroleum depots stocking local detailed issue depots at areas of troop concentration, and the opening of Supply Reserve Depots at Lilyfreld and Bandiana in 1943 to support the Australian and allied forces operating to the north. The strength of AASC involvement in the home base grew to a peak of over 25,000 to meet these liabilities 4; the identification, distribution and operating relationships of the units involved in each State have been covered in Chapters 6-12. It was a massive effort compared with the economy models which had preceded it in the previous war and the peace time forces; it was also one in which the almost invariable solution to a need was to raise a military unit rather than explore the build up of civilian infrastructure to provide an acceptable alternative. The result was an array of military units doing civilian tasks in areas where there was no direct threat, and many of the soldiers committed to these routine and not obviously war-related tasks, particularly those who had volunteered for overseas service to defend their country, bitterly resented being kept away from the action.

Western Desert

Those who had taken the plunge in joining the AIF when its employment overseas was uncertain were rewarded in joining the Middle East command in Palestine from February 1940 to train in preparation for deployment with the British Expeditionary Force in France, but history was about to repeat itself. Included in the force which set up camp at Qastina, then in April at Barbara, were half of 6 Div Sup CoIn, and from corps troops 6 Div Amn Sub-Park, under command of CAASC Lieut-Col N.B. Loveridge DSO, erstwhile CO of Anzac Mtd Div Train in World War 1. The majority of 6 Div Pet coy and 6 Div Amn Coy remained at Puckapunyal awaiting subsequent convoys, the second in May comprising the bulk of those companies. But the third containing 18th Brigade and a section of each of the two companies was diverted to England around the Cape of Good Hope, owing to the threat to shipping which developed in the Red Sea on Italy's entry to the war; thereafter they ceased to be part of 6th Division AASC. From the units then in Palestine a Composite Company was formed to move to Egypt in September with 16th Brigade Group, and three supply personnel sections and a port detachment were raised, from 6 Div AASC and members of the AASC Training Unit, to provide lines of communications support units for the coming operations in Egypt 5.

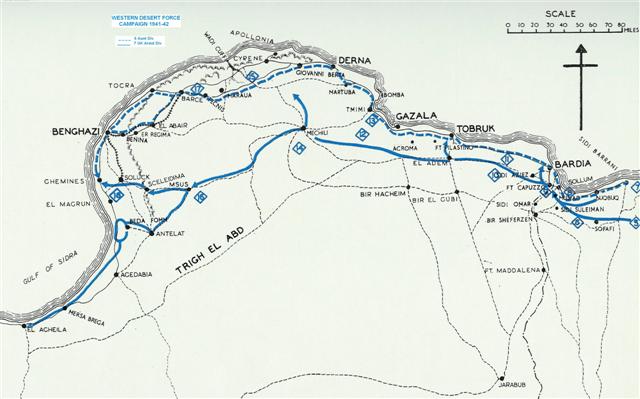

6th Division was concentrated in Egypt in November and, on entry into the Western Desert operations in December, the system of operational support was organised on the RASC Base Supply Depot at the Suez Canal, through the Alexandria Supply Depot, then Field Supply Depots and Forward Ammunition Depots progressively strung out during the advance through Libya and the pursuit into Cyrenaica. These Depots were opened and closed as required, most of them being given consecutive numbers: 1 and 2 Sup Pers Sects controlled FSDs issuing rations and fuel in the rear area at Helouan, Ikingi Maryut and Qasaba, and in forward operations No 8 (Sollum), 13 (Bomba), 15 (Slonta), 17 (Barce), and 18 (Magrun) for supplies and POL; 6 Div Amn Coy operated FADs adjacent to FSDs: No 11 (Tobruk), 13 (Bomba) and 15 (Tecnis), the remainder in the sequence being operated by RASC and NZASC units. The Divisional AASC drew from their own and any other depot where appropriate, issuing to supported units from supply, petrol and ammunition points at convenient locations in their rear. Replenishment of the depots, although normally a third Iine task, was assisted by the divisional AASC, at times supplemented by unit transport, from resupply delivered across the desert road, then through Sollum, Tobruk, Derna and other ports after their capture.

Western Desert Support

The transport picture was grim as the 3 ton 4x2 vehicles brought from Australia were less than suitable and short of repair parts, so when after the fall of Mersa Matruh the units were invited to send a 30 man 'scrounging party' to acquire captured Italian trucks and trailers, this was taken up with alacrity, the 5 and 10 ton diesels with trailers so acquired becoming the salvation of the subsequent transport effort. The transport pool had the task of first stocking the advanced depots, then dumping programmes to establish the ammunition resources for 6th Division's assaults on the fortresses of Bardia 3-5 January 1941, Tobruk 22 January and Derna 30 January; there was then the task of operating the issue points to supply the fighting units with their needs. By the text book, this should have been an orderly affair of corps AASC units delivering from railhead to divisional AASC units, for them to distribute to user units. In practice, HQ AASC had to use whatever resources were to hand to clear from the docks at Tobruk, superseded forward depots or any other source, including captured enemy dumps, and get it forward by any means possible. After the capture of Derna all transport was diverted to infantry trooplift in pursuit of the retreating Italians through Cyrenaica 6. Capt D.M. Russell of 2/4 Bn, who later commanded a scratch infantry unit including an AASC infantry company in Crete, claimed that in Cyrenaica the infantry had to live on captured Italian dumps as 'the AASC was three days behind’ 7; he omitted to look past the floorboards of the trucks they were riding in to discover that the AASC was really with them, carrying the battalions and not supplies in the rear. Another diarist who complained of the ASC's lack of road discipline might better have reflected on what the objective was. It was British General O'Connor's command decision to take the risks in a headlong pursuit which resulted in annihilation of the Italian Tenth Army at some cost to normal maintenance procedures, but with the prize of an absolute victory.

This onwards push resulted in the forward AASC units being up to Benghazi on 7 February and to the line of exploitation in front of Agedabia, at which stage Churchill’s decision to commit forces to the defence of Greece put the force on the defensive, providing the window of opportunity for Rommel's Africa Korps to be inserted into the theatre. The interim breathing space allowed the Divisional AASC to return to Tobruk to begin rebuilding stocks in the forward areas which were relying too much on captured food and fuel; they were also carrying the additional load of looking after nearly 50,000 prisoners in Bardia, but that problem was ameliorated by the ex-garrison's own stocks. On 12 March these tasks came to an end on handover to 9 Div AASC and return to the Delta to prepare for embarkation for Greece 8. On 24 March 1941 Rommel launched his first counter attack from El Agheila and, by outflanking the proposed defensive position at Antelat through Mechili, inaugurated the '1st Benghazi Handicap' back towards Egypt. Blocking positions by 26th Brigade at Tmimi and 20th Brigade at Gazala bought some opportunity for retreating units and stragglers to concentrate at Tobruk, not the least being 9 Div Amn Coy which had been dispersed across Cyrenaica supplying, extricating and destroying ammunition stocks, eventually getting most of its sections back in as well. The last elements arrived in Tobruk on 10 April closely followed by the Afrika Corps 9.

Tobruk

The AASC component of the Tobruk garrison was more than equal to the task, comprising HQ AASC 9 Div, 9 Div Amn Coy, 9 Div Pet Coy, 9 Div Sup Coln and 7 Div Sup Coln, with also under command 309, 345, 346 and 550 Res MT Coys RASC; additional RASC base units under the UK 76 Base Sub-Area included a base supply depot, bulk petroleum storage company, reserve petroleum depot, field bakeries and butchery, cold storage depot, plus two DIDs and two FSDs 10. The static nature of the defence of Tobruk had two major effects on the AASC units: firstly replenishment of units was effected by unit collection from static detail issue depots for food, fuel and ammunition; and secondly the surplus of transport elements so liberated was available for other employment or evacuation from the garrison.

After the initial attacks had been contained, garrison commander Maj Gen L.J. Morshead, concerned to establish the maximum depth in the fortress, decided to raise an infantry battalion from the ranks of 9 Div AASC, though difficulties with support weapons changed this to four infantry companies and a carrier section. On 27 April A Coy and the carrier section commanded by Capt J.C. Taylor relieved 2/43 Bn in 24th Brigade's sector in the east of the line, occupying 4,000 metres of the perimeter covering the Wadi Zeitun from the coast in to the head of the wadi on the Bardia Road, with first 2/23 Bn, Iater 2/43 Bn, on its right. It was to hold this position until immediately before the relief of the Australian troops began in September, the longest stint in the forward line by any unit in the garrison, and a factor recognised by Morshead in scheduling the order of return to Egypt. B Coy was held by 24lh Brigade in reserve until returned to its functional role in July. C Coy was first held in depth at Fort Pilastrino in the Blue Line, then was absorbed into 2/15 Bn, and D Coy (less 10 Pl) into 2/13 Bn, both of which saw heavy fighting in the early assaults and subsequent attacks to eliminate the Salient, taking heavy casualties. D Coy's 10 Pl was formed into a carrier platoon under 18 (Indian) Cav Regt at the western coast of the perimeter, then with 2/1 Pioneer Bn as part of 20th Brigade which also had C and D Coys, while 7 Div Sup Coln supplied a medium machine gun platoon for 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers 11.

The garrison was thinned out in July. The four RASC transport companies were evacuated, replaced by three formed from the AASC. No 1 Troop Carrying Coy, from B and part of A Inf Coys AASC commanded by Capt W.L. Day, was allotted to 18th Brigade to give it mobility for its counter-penetration role. No 2 Troop Carrying Coy from C and D Inf Coys AASC commanded by Capt J.N. Duncan similarly provided mobility to the reserve battalion of each brigade in the line. The third, Area Transport Coy from 7 Div Sup Coln under Capt H.C. Thompson, was used as general transport in the base area. A Vehicle Reception Depot was formed by Capt C.H. Locke in place of the evacuated 76 VRD RASC, and the British detailed issue depots were replaced by 9 Div Sup Coln, the departing ADS&T 76 Base Sub-Area handing over all S&T responsibilities to CAASC 9th Division. It is therefore apparent that the kindest reading of an RASC historian's statement that 'throughout the siege, the RASC with some AASC assistance ran supplies, transport, petrol and ammunition' is that it applied only in part and only to the first part of the siege 12.

Although A Inf Coy occupied a battalion's worth of perimeter, its time in the line was fairly quiet as anticipated, the rugged approaches to its area not being likely to attract any major assault. It was not, however, without its moments: on the night 30 April May a German raid on A Coy's Post 280 was turned away in a fire fight; its carrier section 'patrolled adventurously' and provided part of the supporting fire for a sortie on 13 May by a company of 2/43 Bn and a troop of tanks along the Bardia road, a debacle in which the AASC carriers helped screen the withdrawal 13. Meanwhile the remainder of the garrison's AASC and RASC had settled into the routine of support, running the base, air attacks on their positions and running the gauntlets of fire in moving about their tasks.

Tobruk Defensive Tasks

The range of these tasks was wide and often unusual. 9 Div Amn Coy published Tobruk Truth, issued with the rations to counter rumours and enemy propaganda 14. Ammunition duties, between meeting the expenditure peaks in repelling assaults on the fortress, included the disposal of Italian ammunition, much of it unsafe and the cause of several casualties to the unit. Unloading stores in the port was a hasty affair, the RAN's 'Scrap Iron Flotilla' running the air blockade and having to be turned around within an hour at night; CAASC Lieut-Col J.A. Watson had to raise a port detachment and impose strict transport control to ensure effective discharge in the time available, and Sgt E.S. Hodgson was attached to the Base Sub-Area staff to supervise the tug and lighter crews working the harbour. Misapplication of food, particularly attractive items, was endemic ranging from scrounging extra rations, through organised theft, to medical staff feathering their own nest in the name of the poor patients. An armed security guard with orders to shoot was placed around supply dumps until the previously detached platoon of D Inf Coy AASC was tasked with establishing a security store in the Senussi Cave, operating a rail line from the roadhead to the cave for more easily securable storage of the attractive stores 15.

Tobruk Base Tasks

Relief of the 9th Division by 70th (UK) Division began for the AASC with arrival of the Polish ASC to take over the Area Transport Coy in late August, but a new Res MT Coy had to be formed from the two troop carrying companies to handle movement of the incoming and outgoing divisions through the port. A Inf Coy came out of the perimeter into the reserve line on 9 September, then a month later was tasked with operating the prisoner of war compound, but was relieved immediately and evacuated in the first wave at Morshead's direction on 12 October. HQ ASC 70 Div and its units were in control by 21 October and the main body was evacuated by sea under air attack to Julis Camp in southern Palestine, leaving a rear party of 70 to follow 16. Watson had had under his control nearly two and a half thousand men, a thousand vehicles, several food, fuel ammunition and vehicle depots and workshops, plus a wide range of peripheral duties, as had his men and those detached in the infantry, cavalry, machine gun, rail and medical transport, port and water transport details. The galloping grocers were nothing if not versatile, and did not need elaborate command structures to manage those massive resources, relying on energetic, relatively junior officers to fulfil both routine and independent tasks while controlling significant bodies of men and equipment. The modern trend to have increasingly higher rank to command increasingly insignificant groupings looks bankrupt beside this practical example of can-do, which was not unique, being mirrored in the earlier and later campaigns in the Middle East and Pacific.

Greece and Crete

Withdrawal of 6th Division and 2nd NZ Division from Cyrenaica Force, which had left it so seriously incapable, also committed the departing divisions to an equally impossible mission in northern Greece. The Greek Army itself was similarly overcommitted, having to defend its Albanian border and Thrace but could not continue the defensive line in between along friendly Yugoslavia; so the immediate collapse of the latter left a wide gap through which the German forces poured, onto the Anzac Corps position on the Aliakmon River. The following actions in the campaign were a succession of withdrawals and eventual evacuation, largely at night due to the complete air superiority of the Luftwaffe, in which the AASC transport necessarily figured prominently and consequently lost heavily.

During-the relief of 6 Div AASC by its 9th Division counterpart in Libya in early March 1941, receipt of a 'mutilated signal' sparked the reorganisation of 6 Div AASC into a composite structure for service in the Greek campaign – 16, 17 and 19 Bde Composite Coys under Majs J. Talbot, T.A. Winchester and R.T. Cochrane respectively. 2/1 MAC left for Greece on 18 March, followed from 1 April onwards by the main body of the divisional AASC, 1 Corps Tps Sup Coln and detachment of the 1 Corps Pet Park. A week later 16 and 19 Coys were concentrated in northern Thessaly in support of the Aliakmon Line along a route crowded with troops and refugees, with 17 Coy just landing at Athens. As 19th Brigade was required to defend Vevi Pass forward of these positions, 350 donkeys were hired to support it off the road, and 30 DID was established at Perdika; 16th Brigade was similarly engaged at Veria Pass to the east. The first engagement on 10 April was followed by a precipitate withdrawal to the Aliakmon by the third day where, with the bridge blown, the donkeys were used to move the forward supplies stocks back over an improvised ferry. With a crumbling western flank of the Greek Central Macedonian Army, withdrawal to a temporary line holding the Thermopylai, Brallos and Delphi passes was decided on as the only way of stabilising the situation as a prelude to an attempt at evacuating the entire force from Greece 17.

Business for 16 and 19 Coys and the corps troops units in all this manoeuvring was brisk, carrying fuel, ammunition and rations forward to the brigades, moving battalions first forward then back, and evacuating such units as the Casualty Clearing Station which were not self mobile, playing a critical role in extricating the force from the enemy envelopment. Trooplifting the forward battalions out brought the companies under fire not only from the ever-present enemy aircraft but also from German armour and road blocks, one convoy with 16th Brigade having to diverge around Larissa cross country as the town was in enemy hands. When a convoy of 16 Coy evacuating troops at Pharsala came under attack from a dozen dive bombers Dvr F.L. Craig continued to respond with a machine gun, making himself a target until killed, providing a diversion which allowed most vehicles to get away. His citation with two officer witnesses from division and corps was watertight, but it was endorsed with the mixed recommendation ‘VC or M in D'; this silly vacillation cost Craig and the AASC the chance of award of a Victoria Cross. Another Dvr C.J. Cross of 1 Corps Tps Sup Coln was awarded the DCM for extricating an infantry patrol twice under fire when it was encircled by enemy tanks. Meanwhile 17 Coy, arriving late in several vessels days apart, was used on rear area protective duties, the other companies supporting 17th Brigade. Given initially an anti-parachutist role west of Larissa, its first task was delivering ammunition forward on 16 April, then evacuating ammunition back through Brallos Pass to Levadia as the withdrawal to the Thermopylai Line proceeded.

In the midst of this confused movement a decision was made to add to it by reorganising back to the commodity system of Supply Column, Ammunition Company and Petrol Company, each of the three companies exchanging their supply, ammunition and petrol sections. The composite system was still not understood by division or brigade general staffs, as indeed it was not even a year and a half later in 9th Division at El Alamein: they regarded the three companies as belonging to the three brigades, leaving the divisional troops half of the division and general tasks without any specific resources, so relying solely on the goodwill of the brigades to release the necessary resources. But the restructuring was particularly inexplicable as it was then known that an evacuation from Greece was imminent, and this regrouping moving over congested roads could add nothing to future operational efficiency 18.

Withdrawal to the Thermopylai line began on 20 April, armchair strategists outside the theatre hoping for a rerun of the 480 BCE defence against the Persians, totally ignorant not only of the recession of the sea from the pass in the intervening years leaving a good panzer manoeuvre area, but also of the fact that the historical engagement was no more than a holding operation to force a sea battle in the nearby Malian Gulf, never a considered attempt to defend Hellas on the land. Now there was neither a sea battle in the offing to justify the stand nor any better possibility of a land defence, as the Greek army gave way on the western flank just as the Phokians had so long before. The position was simply used to cover the inevitable evacuation, and was given up in three days as it had been to the Persians, 6th Division falling back to Athens' port and further on to the Peloponnese embarkation beaches. The evacuation of Greece began in earnest.

Withdrawal in Greece

AASC units were fully committed ferrying troops back to the evacuation beaches and defending the aerodromes around Athens, many tending to be among the last to be released for embarkation. An early evacuation party of ex-17 Coy members under Capt J.A.F. Anderson left on the unarmed SS Julia under successive air attacks which the AASC members held off by organised rifle fire. 6 Div Amn Coy (ex-17 Coy) evacuated the infantry and anti-tank unit rearguard from Brallos Pass, and the residue of the companies not committed to airfield defence and troop lifting crossed the Corinth Canal to be taken off near Argos; others were embarked near Athens, but many were stranded when released only after the last ships were gone. During the evacuation from the Peloponnese there was a cry from the infantry 'save the infantry'. While there may have been some logic in extricating scarce trained and battle-experienced battalions, there was similar logic in preserving scarce trained and experienced combat support and service support units. Avoidance of this inescapable logic is reflected in official histories in which the army and air force support troops are presented as a disorganised rabble, and from there that which passes for reasoning goes on that they were therefore expendable. The evacuation was spread from 24 to 27 April, and was effective in getting the best part of the whole force away but 6 Div AASC lost 229 prisoners – 20 percent of its strength and the greatest proportion of any organisation; 1 Corps Amn Park and 1 Corps Tps Sup Coln lost one and 23 respectively. Of course the rearguard is the position of honour and, although this would not be at the forefront of the minds of the planners of the evacuation or indeed of those today who have difficulty in giving service soldiers their due as a worthy part of the army, these AASC rear parties shared that honour with the infantry who were also sacrificed to hold the enemy back from the embarkation points 19.

Between 25 and 29 April remnants of Anzac Corps were disembarked on Crete, though some went directly to Alexandria. The main elements of 6 Div AASC were concentrated at Neon Korion, later escapees continuing to dribble in. There were only limited tasks, no vehicles being available: opening detail issue depots at Georgiopolis, Neon Korion, Retimo and Steelos from which units in the defensive positions drew their food, fuel and ammunition; and patrolling the Suda Bay area. As no transport and few weapons were landed, as many as possible of the divisional AASC were onloaded to Egypt, including HQ AASC 6 Div, leaving 19th Brigade AASC Officer Capt W.A. Bunting overall senior AASC officer. After patrolling duty around Neon Korion 2-9 May, most of those not actually manning depots had to give up their rifles, bren guns and ammunition to infantry who had not brought theirs out from Greece, and were evacuated to Egypt on 14 May. Others were incorporated into the defensive layout. The need to cover such a length of coast and also potential paratroop landing areas led to the formation of special fighting units from Army and RAF support organisations whose primary function no longer existed. Composite battalions were formed for Creforce of which one company was put together by Capt D.M. Russell, Transport officer of 19th Brigade, from 89 AASC members and drivers from HQ 27th Brigade who had been evacuated from Greece without their weapons. Armed with .30 Springfield rifles from a destroyer, they were called Rusty's Rifles and used in the Neon Korion airfield-Suda Bay sector 20.

Resupply from the RASC BSD at Kanea to Retimo was arranged initially by hired caique. Capt H.A. Morgan commanded the Retimo depot, Lieut B.W.T. Godly at Neon Korion, Lieut L.J. Tinker at Georgiopolis and Lieut C.H. Rivers the Steelos ammunition dump. The airborne invasion on 20 May was contained by Australian, British and Greek defenders at Suda and Heraklion, but succeeded at Kanea through the failure of New Zealand brigade commander Hargest to counter attack promptly at Maleme airfield, and so the island was lost. During the first week of fighting resupply from Kanea ceased, the force having to live on half rations from reserves and Lieut Godly arranging with the village mayor to bake bread and supply meat, for which the mayor and fifteen helpers were later executed by the Germans. Air attacks were minimised by good camouflage discipline but, after the local surrender, attempts by small parties to get to the evacuation beaches on the south of the island met with little success, most being hunted down and captured in the mountains: 68 were taken prisoner, while a few made daring escapes in company with members of other arms in an assortment of vessels 21.

At the end of May there was reassembled at the 6 Div AASC camp at Julis 556 men – just over half of those who had left there two months before. More drifted in from Crete, and the final tally from the 1,015 which had begun the campaign was 31 per cent killed and captured. From this slim remaining base the units were rebuilt, and the CAASC was given responsibility to put together 1 Aust Corps Troops – the Supply Column, Ammunition Park, Petrol Park, Ammunition Company, Supply Personnel Section, Reserve MT Company and Anti-aircraft Brigade AASC Company. But the attention of 1 Aust Corps had now been firmly directed to another operation to the north.

Syria

Not content with his Dardanelles-like misjudgement in Greece and Crete, Churchill then pressed for an equally misjudged 'walkover' capture of France's Syrian territory from the Vichy French forces, in which 7th Division was to be the major attacking formation. The growing realisation that commodity units did not provide adequate flexibility for the support of mobile operations or different phases of war, as had become well understood in World War 1, resulted in a regrouping into a composite company structure: 7 Div AASC Amn Coy as 21st Brigade Group ASC Coy, 7 Div Pet Coy as 25th Brigade Group ASC Coy and the borrowed corps troops 3 Amn Sub-Park plus Sup Pers Sect forming Div Tps ASC Coy. Allocation of the brigade titles was, however, a now repetitive mistake as the brigades again contested control of the units with the CAASC, so to reverse this they were renamed later as 4, 5 and 6 Coys to match the numbering system of the Artillery, Engineers and Field Ambulances, which were similarly and necessarily controlled at divisional level 22.

The RASC established FSDs at Acre and Rosh Pinna, FADs at Qirat Motskin railhead and Rosh Pinna from which the companies were to replenish. In order to meet the third line requirement to bridge the growing gap which the planned advance would open up, and for the troop carrying duties for which there was no capacity within the lean divisional companies, a Composite Res MT Coy was formed by Capt L.F. Stansfield from elements of the brigade companies, 2 Amn Sub-Park of 1 Aust Corps Amn Park and RASC units. The attack commenced on 8 June, 21st Brigade along the coast road, 25th Brigade Rosh Pinna-Metulla. As the advance continued, the condition of the inland roads soon made it expedient to support 25th Brigade from the coast road when a lateral road became available. There was also a period when Berryforce at Merdjayoun had to be supported so a composite group of elements from each of 25 Bde and Div Tps Coys was left at Rosh Pinna for this task until the responsibility was passed to the RASC. Thereafter 7 Div AASC followed the advance, establishing supply, petrol and ammunition points as dictated by the position of the forward units and forming ammunition dumps for the guns, culminating in the buildup for the Damour battle.

Support in Syria-Palestine

It quickly became apparent that gun ammunition expenditure was far higher than predicted, resulting in continuous running and several dumping programmes to accumulate stocks forward. With a shortage of vehicles from the start, the allocation to the ammunition, petrol and supply sections of each company had been carefully calculated to meet the expected tasks with no spares, so when the demand for 25pr ammunition escalated there was little flexibility to switch vehicles from other tasks, the alternative being simply continuous running and overloading. This might have produced a diminishing return on overtaxed men and equipment, but in view of the lack of spare capacity, arrangements had been made to form maintenance teams to both keep the vehicles in operating condition and let drivers rest after long shifts. For the six weeks of the campaign, despite the difficult inland roads and enemy artillery and machine gun fire, resupply was fully maintained, but a strong criticism to come from these operations was a serious lack of understanding of the system of replenishment by the forward units. While the AASC companies were eager to meet all demands, wooden headed staff officers of the brigades ordered unnecessary forward dumps of commodities which had no relation to tactical plans and needs, and artillery staff officers called for ammunition deliveries which, on arrival at the gun positions, were 'neither expected nor welcome', a wasted effort in an already overstretched replenishment system. Damour was taken on 9 July, an armistice following three days later, and a period of garrison duty followed, taken over by 9th Division after its release from Tobruk from mid-January 1942.

While the distances involved had not been great by Western Desert standards, the poor roads and tracks and very limited transport available had stretched both divisional and corps AASC units. As well as the standard maintenance and trooplift tasks there were others of a less usual nature: the Composite Res MT Coy was responsible for receipt and evacuation of captured French vehicles; some special elements were also manned – the Salvage Unit recovering usable materiel as the advance progressed, and a prisoner of war holding unit for each brigade. There were also augmentations from British artillery and anti-aircraft units, whose RASC detachments were incorporated in the 7 Div AASC companies and used on general support tasks as well. It was a short, intense campaign whose success from the AASC viewpoint was summarised by CAASC Lieut-Col H.M. Frencham as due to 'skill and courage of MT Drivers, discipline and devotion to duty of all ranks, skilled leadership of Officers and NCOs'. He might also have mentioned the careful forward planning, flexibility of approach to problems and extensive training which are so essential to success under operational pressures, but this takes nothing away from the performance of the men and the units 23.

After conclusion of the Syrian campaign, although there was a garrison task sideline, activities centred largely on reforming 1st Australian Corps as a properly constituted formation to meet the original objective, as was eventually achieved in World War 1, of having all Australian troops under national command and fighting as an entity. It had been a parallel objective of the British command to keep 'colonial' formations at the lowest level possible to facilitate their dovetailing into the British structure, and this tug of war had been active from the beginning, sometimes for urgent operational necessity, but always resisted by Blamey. Now the three divisions were out of contact, the situation in the Middle East had stabilised, and 1st Armoured Division was training and equipping in Australia to join 1st Corps and give it the punch necessary for operations in North Africa. But the other side of the coin was mobility, so the miscellany of AASC non-divisional units was restructured to form a corps troops transport column to resupply the divisions, a corps troops column to provide direct support to the mass of corps troops units, and a troop carrying column able to lift a division at a time. This aggregation of transport numbering over a thousand task vehicles was the greatest assembled in one command in the history of the AASC, but was not used in operations as Japan's entry into the war resulted in the recall of the 6th and 7th Divisions to the defence of Australia. Movement of 1st Armoured Division was cancelled, only 9th Division remaining in the Middle East to provide infantry backbone for the breaking of Rommel's power in the Western Desert.

El Alamein

The first half of 1942 was taken up by 9th Division after its relief from Tobruk in retraining and refitting in preparation for the battles ahead. At the beginning of the year the divisional supply column, ammunition and petrol companies finally converted to the composite system, becoming 10, 11 and 12 Coys AASC, each with three transport platoons and a composite platoon for supplies, petrol and ammunition duties. They were concentrated at the El Alamein defensive line by 11 July with 101 GT Coy from the departed Corps Troops Transport Column and 345 and 462 GT Coys RASC. Another addition was found to be a necessity – a Divisional Troops Company to look after the non-brigade units and corps units operating permanently with the division – this was raised by milking each of what was termed the brigade group companies and 101 GT Coy. The divisional staff still did not properly understand the use of the composite system, allotting companies to brigades, as opposed to each company supporting one third of the division, so forcing a shortfall which was not intended to exist. It was not until the very eve of the battle that the confusion of trying to coordinate into a divisional effort three companies, each claimed for priority by a brigade, was recognised, leading to a hasty reversion of them to control by the CAASC.

Preparations for the defensive battle of Alam Halfa, then the following offensive battle of Alamein, included the stockpiling of five days of commodities to cope with the usual German attempt at armoured encirclement. Fuel was supplied by RASC bulk tanker direct to most divisional units, with reserve stocks held in 44 and 4 gallon drums, until reversion to packed fuel replenishment through petrol points was made on the eve of the battle of Alamein. Issue of rations to units was effected through the new clockface method, where unit vehicles were loaded from vehicles positioned tailboard out in a circle. Water was issued through water points to unit water trailers and containers, with a divisional reserve in cans. 101 GT Coy under Maj A.H. Singleton was involved in building up reserves for the battle, particularly ammunition in early October. AII this was facilitated by the static nature of the defensive line and the steady build up, in Montgomery's usual way, of a large margin to ensure success. As part of an elaborate cover plan Capt E.P. Brandwood of 11 Coy took most of the Division's domestic vehicles on a 3 day trek south, stirring up as much dust as possible. Brigades drew hard rations regularly so that this would not become a warning of an impending attack, and gun ammunition reserves delivered into the forward areas, some of it prepositioned in front of the forward defended localities ready for use in the advance, were carefully camouflaged before morning 24.

Opening the attack on 23 October 1942 with 900 guns along the front created the anticipated drain on gun ammunition, which had been prepared for in the build up. In 9th Division's area 101 GT Coy had done that job in advance and now had the capacity for troop lifting, shuttling battalions to their forming up places, often under artillery and small arms fire. The efforts of the four divisional companies were notably unspectacular in execution, which reflected the careful preparation, high state of training and cool execution of tasks on time and under fire during the battle. Montgomery's 'crumbling operations' on the coastal sector in the middle of the battle, largely carried by 9th Division, created a heavy load in trooplifts and delivery of ammunition into the fighting area, and the flexibility of the composite system in a time of low food and fuel usage came to the fore. While the AASC companies were spared the heavy toll on the infantry, divisional commander Morshead was unequivocal in his appreciation of their 'excellent work', Watson receiving a DSO.

By 4 November the enemy withdrawal was in full swing and the companies had moved forward to operate from the Tel el Eisa station area. The following day they were tasked to lift 151st Infantry Brigade forward, ammunition and rations being dumped on the ground. This was then changed to supporting an advance by 20th Brigade, but this and then another troop lift task were cancelled to make 9th Division available for its foreshadowed return to Australia, a need subsequently accentuated by the failure of the American division sent to Papua as a quid pro quo for the 9th's retention in North Africa. When this confusion had ended, the companies were left with the task of recovering unexpended gun ammunition of 9th Division and 51st Highland Division to depots, then were returned to Palestine to prepare for return home 25, the heroes' welcome given to 9th Division which had been denied to 6th and 7th Divisions on their return in the less leisurely period of the early Japanese threat, and training for the assault on Lae.

Malaya and Singapore

Plans for the defence of Malaya and Singapore embraced an unfortunate paradox. Commander in Chief Far East Air Marshal Brooke-Popham, in an operation order issued in January 1941, assigned defence to the Fleet, acknowledged its absence, therefore went on to allot interim responsibility to the Air Force, acknowledged that sufficient aircraft had not arrived, therefore went on to give responsibility to the Army. The same order accurately predicted actual Japanese landing points, but instead of ordering ground force deployments accordingly, doubled back to make the fighting units responsible for defence of airfields, so hamstringing Army freedom of action for its main task 26.

AASC units in the theatre were in two distinct categories. The first was 8th Division's second and third line support which comprised 8 Div AASC commanded by Lieut-Col L.J. Byrne (headquarters, supply column, petrol company, ammunition company and workshop, less the sections remaining in the Northern Territory committed to the brigade kept back to defend Timor, Ambon and Rabaul), 8 Div Amn Sub-Park, a section each of 9 Petrol Sub-Park and 1 Field Bakery, 2/2 Res MT Coy and the AASC ambulance transport sections in 2/9 and 2/10 Field Ambulances. The second group comprised the general support units of 2/3 and 2/4 Res MT Coys, and 2/2 and 2/3 Motor Ambulance Convoys, which were employed in support of various formations throughout the theatre, according to the needs at the time. Base supply and transport support was provided from the British infrastructure drawn on by 8 and 9 Sup Pers Sects. That the 'story ... after the outbreak of war ... should perhaps be more properly called the story of the Imperial ASC’ in an RASC account of the campaign is just another of those unfortunate statements which pervade British accounts of operations involving Australian and other Commonwealth armies, and unfortunately the silence of Australian historians on the AASC's role and exploits does nothing to counter such an impression.

Although 8 Div AASC was organised initially in the conventional supply-petrol-ammunition unit model, the division's initial deployment as two separate brigade groups from Australia, and then as defence forces at Malacca and Mersing on the Malayan west and east coasts, resulted in a reorganisation into two brigade composite companies, first called 22 and 27 Bde Coys, then in October redesignated as 1 and 2 AASC Coys. Byrne was designated CAASC AIF Malaya, responsible for the full range of divisional, corps and base AASC units now deployed in the theatre. A further addition was the formation, from the existing units, of a water Transport section commanded by Capt R. Concannon, operating along the coast between Mersing, Endau, Mawai and Johore Bahru 27.

2/3 Res MT Coy was specially raised in Australia under command of Maj C.M. Black at the request of the British Government to help meet a deficiency of general transport in the theatre. As the AIF was experiencing recruiting difficulty and as the company was intended for rear area duty, by mutual agreement it was raised from the 35-45 age group, but the prevalence of members wearing World War 1 ribbons showed that many had lowered their real age to gain enlistment. It was attached to 11th Indian Division in the north and so, contrary to intention, was involved in the thick of action from the very beginning of the campaign. On 8 December 1941, the day of the landings, two sections under Capt G.A.C. Kiernan moved 3/16 Punjab Bn towards The Ledge in Kroh Force's preplanned attempt to seal off the anticipated Japanese landing and thrust south from Patani. When the battalion was being outflanked on 12 December, the spare drivers fought as infantry to help extricate the unit, which was then withdrawn in the 2/3 Coy vehicles. This supposedly rear echelon unit was the first Australian unit in ground action, the next being a similar unit, 2/2 Res MT Coy; the first infantry unit involved was 2/30 Bn at Gemas over a month later. The Company then continued its forward area operations, with elements involved in such diverse extra-curricular activities as airfield defence, vehicle-mounted machine gun patrols, operating the ferry to Penang, and at the direct request of the 3rd Corps Commander, forming an armoured car unit to counter a breakthrough along the Grik Road. The unit went on to 'support every brigade fighting in Western Malaya', attracting widespread approbation of its effectiveness and coolness under fire; its final task was to help move the main body of 8th Division over the Causeway from Johore to Singapore 28.

2/4 Reserve MT Coy was based on Singapore and, reinforced by 50 impressed trucks with Chinese drivers, operated as part of the theatre general transport pool, working round the clock delivering forward to dumps in Kuala Lumpur, lifting troops to the front, evacuating them, and finally salvaging ammunition in the withdrawal. 2/2 Res MT Coy was in direct support of 8th Division, often interchanging with the divisional companies, providing the forward link from the base to 8th Division, moving the battalions to their belated contact with the enemy in Malacca, subsequently taking over the function of 8 Div Amn Sub-Park to release it for troop carrying, then taking on this role itself for 2/19 Bn for the Muar operation, finally participating in the lifting of the Division back to Singapore 29.

Until 8 January, 1 and 2 Coys fulfilled routine duties in support of the garrison tasks of 27th Brigade at Kluang and 22nd Brigade at Mersing, seeing little of enemy action other than air attacks on their convoys. Thereafter the pace quickened, Westforce was formed with Byrne as its CAASC commanding 2 Coy, CRIASC 9th Indian Division, 45 and 53 Bde Tpt Coys. This grouping supported the fighting from Muar back to Johore Bahru, while 1 Coy remained on the east under command of 3rd Indian Corps, and 8 Div Amn Sub-Park carried out third line ammunition replenishment and troop carrying. By 31 January all units, including the ambulance and water transport ones, were back on Singapore Island and 'to this date all demands for ammunition had been met, and no ammunition had been abandoned by the AASC' 30.

Support in Malaya

Withdrawal to Singapore meant that, in the confined area, much of the AASC units had no legitimate technical employment. 1 and 2 Coys and 8 Div Amn Sub-Park hived off 3 Coy under Capt A. Mull to support 44th Indian Infantry Brigade; 2/3 Res MT Coy was shipped on the Kinta to Java, manning deck and engine room in place of the deserted crew, to join the anticipated 1st Australian Corps which was to become the core of defence when it arrived from the Middle East; part of 2/3 Motor Ambulance Convoy was embarked on the hospital ship Washui for Australia; and 2/2 Res MT Coy was allotted part of the northern perimeter of the city on the Japanese GoIf Course between Gurkha and Engineer troops. 1 and 2 Coys and 8 Div Amn Sub-Park also hived off 1 and 2 Inf Coys AASC each with four platoons, under Lieut F. Hiddlestone and Capt J.S. Millner, to form part of the scratch infantry Special Reserve Battalion with the depleted 2/4 MG Bn, as part of 22nd Brigade at Tengah Airfield, then fighting their way back to become part of the 8th Division perimeter around the west of the city. 3 Coy was disbanded, 1 Coy established a supply dump and 2 Coy an ammunition dump within 8th Division's perimeter for the anticipated defensive battle. 8 Div Amn Sub-Park kept up ammunition to the guns and infantry until two days before the capitulation, when most of its men were absorbed into the defensive line with 2/26 and 2/30 Bns 31.

This defensive line around the city, committing the ammunition-starved Japanese force to intensive fixed place and street fighting against twice their numbers, was wantonly surrendered by demoralised commanders out of touch with the capacity and spirit of their troops. After losing 191 members in action, 1,907 undefeated AASC soldiers together with the remainder of the garrison in Singapore went into unwarranted captivity on 15 February 1942.

The Island Garrisons

After the collapse in Malaya and the Philippines the only real forward area of resistance which could be contemplated was centred on Java, where the American, British, Dutch and Australian (ABDA) Command was created under Wavell, based on a cruiser naval force, two Dutch divisions and an assortment of allied army and air units. It had been envisaged that 7th and 6th Divisions now returning from the Middle East would form a pivotal element of this force, but the speed of events in Malaya left the Australian component of this force, designated Blackforce and placed as usual under British command, at the less than brigade strength of 2/3 MG Bn, 2/2 Pioneer Bn and other elements. Included was the bulk of 2/105 GT Coy under Capt C. Howitt returning from the Middle East which, with units of other arms, was reprieved from landing at Palembang for airfield defence duties, only to be disembarked instead in Java on 18 February 1942. 2/3 Res MT Coy was also added to the force after its withdrawal from Singapore, its organisation being adjusted to create a supply column for the Force. 2/105 GT Coy was used initially to defend Batavia's Kemajoran Airfield and provide transport detachments for ambulance duties then, reinforced from 2/3 MT Coy and other units, it also established a 70 vehicle troop carrying group for the reaction element of the Force concentrated at Buitzenorg. The Japanese landed from 28 February onwards and, as the Dutch resistance crumbled then collapsed, Blackforce, supported and moved by 2/3 Res MT Coy and 2/105 GT Coy, withdrew through Bandung towards Pameungpeuk on the south coast hoping for evacuation but without prospect of this or effective resistance, it was surrendered on 9 March 32.

Growing likelihood of a Japanese thrust to the south had led a year earlier, in February 1941, to plans being prepared to establish garrisons at Ambon, Timor and Rabaul for airfield defence. They were ill conceived, manned and supported, as the protests of the field commanders and events demonstrated 33, but like the decision to sacrifice Blackforce, were also essentially political decisions, made on an inadequate military appreciation and comprehension of the risk-effectiveness tradeoff. At least these mistakes might have provided lessons for later defensive actions, yet they were not taken in the following operations in Papua, where remote commanders and staffs in Australia not only had little or no understanding of conditions in the combat area, but also made no effort to see and understand them until the crisis was over.

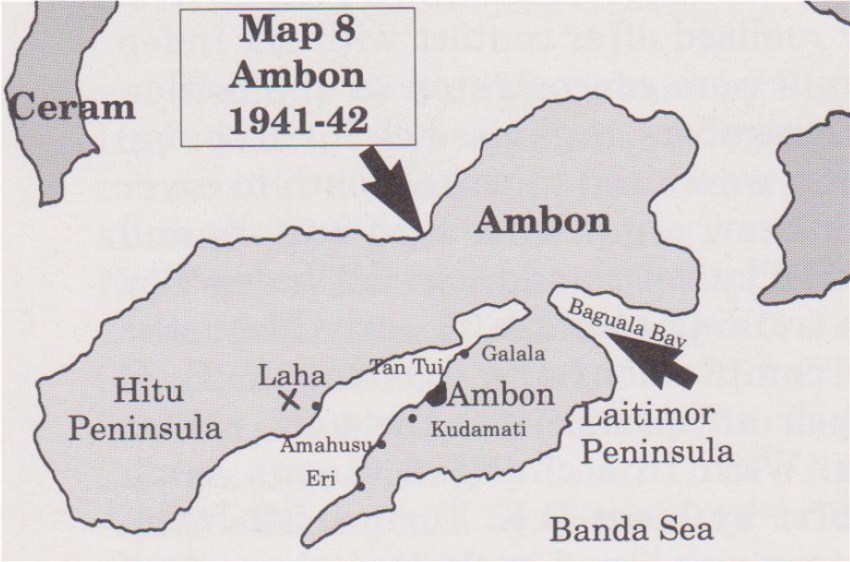

The first force, 2/21 Bn Group designated Gull Force, was landed on 17 December 1941 to protect RAAF aircraft at Ambon; the aircraft were eventually withdrawn but not their supposed protectors. The AASC element commanded by Capt J.R. Burns had been cobbled together with transport, supply, bakery and butchery elements totalling 40 members in Sydney in July, moved to Darwin and dispatched to Ambon on 14 December 1941. The main supplies and ammunition stocks were held at Laha Airfield, defended by two infantry companies, while immediate stocks, bakery and butchery were initially positioned at Galala. A Japanese landing on the north of the island eventuated on 30 January 1942, then a second landing at Baguala Bay the following day outflanked Dutch defences there, so the AASC element and its stocks from Galala, under Capt S.A. Rose, were moved to Kudamati to join the B Echelon of 2/21 Bn. In the following Japanese attack the position held out and was bypassed, but as the rest of the battalion on the Laitimor Peninsula surrendered on 3 February, those elements in the Kudimati position had no alternative but to follow suit. At Laha, attacks had begun on 31 January, with the force holding out until 2 February. The AASC element there was more actively engaged in the defensive fight – a tribute to one Dvr Doolan who was reputed to have successfully ambushed three truckloads of Japanese appears in Chapter 20; Capt Burns and other members were missing at the end of it. After the surrender in both areas, half of the AASC detachment was taken prisoner, the remainder being battle casualties or beheaded by the Japanese after capture 34.

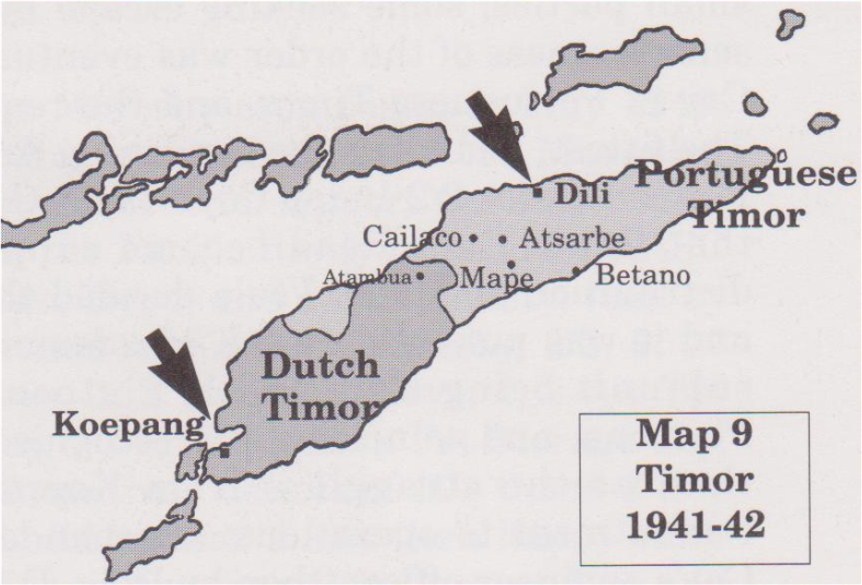

A parallel Sparrow Force, comprising 2/40 Bn Group, was dispatched to Timor to protect the airfield used to stage aircraft to Java. The force landed at Koepang on 14 December 1941 and a detachment based on 2/2nd Independent Company was then sent north to Dili in Portuguese Timor. The AASC Sparrow Section comprised a 42-strong supply and transport detachment formed in Sydney in July 1941 by Capt J.F. Read, moved to the Northern Territory, and embarked for Timor on 7 December 'with much enthusiasm' after three and a half months of fatigue duties and training at Darwin and Noonomah. In view of the precariousness of the defensive positions Read was obliged to effect a supply plan based on a series of dumps, the establishment of which occupied the detachment until the invasion. Following their quick success at Ambon, the Japanese moved on to Timor, landing at Koepang and Dili on 20 February 1942. While 2/2 Indep Coy extricated itself inland, the landing force in the south trapped 2/40 Inf Bn against a blocking force of paratroops and, cut off from its supply base and short of ammunition, it was forced to surrender.

After this surrender, newly arrived Sparrow Force commander Brig W.C.D. Veale moved his headquarters north towards Portuguese Timor with a guard of AASC members and walking casualties. On 1 March, after receiving advice of a Japanese approach, he ordered every man for himself, Read distributed the remaining rations, and the 250-strong survivors broke up into small parties, some seeking escape by sea, others overland to the north. The senselessness of the order was eventually realised after contact with 2/2 lndep Coy in Portuguese Timor, and the remnants were concentrated on the border. The fittest, including the remaining AASC members, organised as K (Koepang) Platoon under 2/2 Indep Coy's Lieut C. Doig, were used to patrol south to cover that flank. Capt Read became supply officer, organising food supply and distribution at Mape. Veale decided that K Platoon should join 2/2 lndep Coy and it was put into a week of commando training at Mape in early May, the sub-unit being renamed D Platoon to complement the existing A, B, C Platoons, and coincidentally recognise their acceptance into the unit, rather than as the stragglers from Koepang. With this changed status came commitment to operations: commanded first by Lieut D.K. Turton, 2/2 Indep Coy's engineer officer, then by Doig. D Platoon was based in the Atsarbe area of the arc which the Company strung around the Japanese forces based on Dili. It saw continuous action, first three months of successful aggressive raids and ambushes, then from August as reinforced Japanese took the initiative, in defensive operations culminating in their evacuation to Darwin on 11 December 1942 35.

An initial 25-man supply and transport unit drawn from 8 Div Sup Coln and designated AASC Rabaul was lodged at Rabaul in May 1941 to support the 2/22 Bn group known as Lark Force; also included was the AASC transport element of the detachment of 2/10 Fd Amb. The prospects for this force were as bleak as those of the sister battalion groups at Ambon and Timor, however the opportunity for the type of resistance offered in the latter was negated by lack of preparation. Although the AASC detachment commander Lieut R.I. Allen proposed to HQ 8 MD at Port Moresby that he cache supplies and ammunition in the mountains it was ignored as 'defeatist', a tag which brought dismissal of the commander of the Ambon force; the only effort made was a late and too limited local one by the battalion second in command to move some part of the supply stocks at the airfield to the rear of the position.

The Japanese assault on 23 January was in sufficient strength to break resistance by the end of the day, the garrison falling back to the south without any pre-arranged escape or reassembly plan. The attackers, intending Rabaul as a main base for operations in the South West Pacific, were thorough in pursuit and elimination of the fugitives, culminating in the execution of about 150 prisoners in the Tol Plantation area. Of this group, Dvr W.D. Collins of 2/10 Fd Amb was shot twice and left for dead, but survived to join a 160-man escaping group organised by 2/22 Bn company commander Maj W.T. Owen, who got them to the vessel Laurabada organised by District Officer J.K. McCarthy and back to Townsville. A previous similar sized group led by another company commander Capt E.S. Appel included Sgt A.L. Frazer and Dvr J.C. Ross of the AASC Detachment, getting back to Cairns on another of McCarthy's vessels the Lakatoi 36. A total of over 400 escaped out a force of 1,400 which had become another dismal sacrifice of penny-packeted forces whose function had evaporated before they were attacked, but were left to inevitable defeat for political purposes on Wavell's principle of not giving up territory without a fight, regardless of the profitless losses involved.

Rabaul Evacuation

Defence of Papua

Buildup of a military base in the Port Moresby area began in May 1940. Included in this was an embryo unit designated AASC Port Moresby, comprising a small supplies and transport element to support the small force allotted. This grew after Japan's attacks in the Pacific firstly to an HQ CAASC NG Force with 9 Coy, 141 GT Coy, NGF Base Depot and 13 Fd Bakery, then by a year later to a DDST on HQ NG Force and ADST Port Moresby, 2/2, 9, 25 Coys, 2/102, 2/105, 2/106, 141, 152 GT Coys, 1, 2 Pack Tpt Coys, 1, 2 Air Tpt Sup Pls, 2/1 MAC, 2/3 DID, 15 Sup Dep Coy, 2 BIPOD, 1 Bulk Pet Storage Coy, 2 Farm Coy, with HQ Comd 11 Div AASC and rear details of HQ Comd 3 Div AASC also in place by early 1943 37.

The build up was a less than happy story during 1941 and 1942, until the imperative of Japanese landings at Lae and Salamaua on 7 March 1942, Finschhafen on 10 March and Gona on 31 July, followed by the thrust through Kokoda towards Port Moresby, forced a change from the tropical ennui of both Administration public service and base military command – the former replaced by the military Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit, the latter by Headquarters New Guinea Force. The effect of the Japanese attempts on Port Moresby and Milne Bay was to galvanise Land Headquarters into pouring increasing supply, transport and construction effort into the bases in the all too familiar pattern of post-trauma oversupply. In consequence, while the force was starved of basic needs in the early critical period, over the following two years when the threat had subsided and operations moved to the north coast, an unnecessarily large component and installations were retained in a base which became progressively less used as ships resupplied direct to bases on the northern coast and islands.

The Japanese thrust from Buna made first contact with 39th Battalion on 23 July 1942 at Awala, pressing on through a strong rearguard action to take Kokoda and its only forward airfield on 10 August. From there the advance continued until, opposed by an effective brigade position at Imita Ridge and having outrun its supply line, the enemy force was stopped and then made a clean break in withdrawal on 27 September. Loss of the Kokoda airfield had earlier meant a similar crippling resupply situation for the two defending Militia battalions, then for the two AIF brigades rushed in piecemeal to stem the advance. While insertion of fresh units was necessary to replace exhausted and broken battalions, they simply added to the difficulties of maintenance over a single foot track through the mountains, so it was not until the defence was pressed back to the southern end of the Kokoda Track that it could receive reliable resupply, and the problem was inherited by the invaders.

The Track was 80 km from the roadhead at Ower's Corner to Kokoda, but this was best measured as eight days walking time. Initial deployment of 39th Battalion forward of Kokoda was supported from supplies landed at Kokoda, then delivered forward by native carrier lines organised by ANGAU. In the withdrawal after loss of the airfield, when the three battalions of 21st Brigade were moved forward over the Track, the available carrier line capacity which could be recruited locally was completely inadequate for even rudimentary maintenance of the units. Expedients were tried at various stages of the route to provide alternatives. New Guinea (1st) Independent Light Horse Troop was put together by AASC horsemen mustering local horses and brumbies to cover the first leg, but could not negotiate the steep mountainsides and steps forward of Uberi. Attempts to air drop supplies and ammunition on to the dry lake beds at Myola were limited to mostly free drops by both shortage of parachutes and aircraft, and eliminated by withdrawal past the area. New Guinea Force Commander Maj Gen Morris, an ex-DST, in the early stages was given one or two aircraft on odd occasions, told that there were only 30 transport aircraft in Australia; asking for merely two on line, he might well have then asked what battles were going on in Australia which had priority over the defence of the Port Moresby base so desperately wanted by the Japanese 38.

During the withdrawal phase there was essentially no effective supply system, which did little credit to either the planning or the general and supplies and transport staffs. While Lieut Edwards of New Guinea Force AASC at Myola was doing his level best to control the supply situation forward, he was not informed of the incoming 21st Brigade and was demanding support for the existing two battalions only; as well much of the supplies sent by air from Port Moresby simply did not arrive at Myola, being either dropped in the wrong place or jettisoned without advice to New Guinea Force which consequently did not comprehend the seriousness of the shortages forward. To restore the position a 2/4 Coy detachment under Sgt Chesterman and Brigade AASC Officer Capt G.J. Hill were sent in to take control on 23 August.

Organisation and response along the Track behind them was even more chaotic: failure of these elements to show the initiative, inventiveness, and spirit of service at any price which was the usual hallmark of the AASC comes largely down to the fact that odd individuals were sent in, accompanied by an assortment of untrained helpers, and without a unit or headquarters controlling either their activities or the line of communication as a whole. Lieut H.T. Keinzle of ANGAU organised the carrier lines, a few supplies personnel organising the dumps established at the staging posts. This changed as a new attitude was instilled into the support structure by HQ 7 Div AASC taking control of the Track on 10 September which, together with its 2/4 Coy and other elements, began to give some form and reliability to the system. From Base Supply Depot Sogeri and Ilolo a platoon of 2/5 Coy delivered by 3 ton truck to Newton's Depot, then by 2/4 Coy jeep to Ower's Corner roadhead. From there to the valley floor .5 km was covered by flying fox, then 1.5 km by NG LH Tp, then carriers forward of Uberi. An officer of 7 Div AASC was located at each depot in the way stations along the Track, and members of 2/4 Coy augmented then replaced the New Guinea Force members who had been established to cope with two battalions and had to cope with two brigades.

Kokoda Track Supply Line

In October 1 Pack Tpt Coy arrived and operated from Ower's to Imita, including establishing a flying fox over the flooded Goldie River. As the advance pressed on, carrier lines delivered bare essentials forward until dumps from air dropping could be established successively at Nauro, Menari, Efogi and Myola. Alola provided little capacity and it was necessary until Kokoda was retaken for infantry to supplement the carrier lines in getting supplies and ammunition from Myola forward. But when Kokoda was secured on 2 November, first air dropping then air landing allowed delivery of requirements direct and the Track was superseded as lifeline to the force, although the depots had to be maintained for several weeks until 600 sick and wounded at Myola had been evacuated. A depot was established at Kokoda and resupplied by air landing, but forward operations to the original contact point at Wairopi over the following fortnight had to be supported by carrier line supplemented by air drops to supply bases every few miles on the way, 2/4 coy eventually operating 16 depots simultaneously between Uberi and Wairopi. This sequence was repeated at Popondetta where development of an airfield enabled air landing of stores and subsequently, in improved terrain, 3 ton trucks along the Sanananda Track and jeeps on the Soputa-Jumbora track greatly curtailed the need for carriers. However operations forward still needed air supply, and with the primitive dropping methods used, the percentage of recoveries was variable and potential for damage ever present: every round of small arms ammunition had to be gauged in the chamber of a Bren gun by the AASC ground parties, before issue to ensure that they were undamaged, and other natures of ammunition inspected and repaired if possible 39.

As part of the defence of Papua a garrison based on 7th Brigade Group was located at Milne Bay in July 1942 to protect airfields being constructed there and to secure it from use as a base against Port Moresby. At increasing threat brought reinforcement by 18th Brigade and Headquarters C Force to command the garrison. On 25 August it was attacked by a Japanese marine assault force which advanced as far as the No 3 airfield at the head of the Bay before being driven off, the remnant evacuated by 7 September. Maintenance of the force was to be by the US Army Service of Supply, which in practice unloaded supplies direct to a depot operated by Maj H.C. Snell's 25 Coy which then issued to all units, Australian and US, army and air force; ammunition and fuel were held in dispersed dumps, unaccounted for, unprotected and in unknown quantities. Formation of HQ AASC C Force commanded by Lieut-Col C.M. Walker ex-CAASC 1st Division, with 2/2 and 2/6 Coys provided the control and wherewithal to get this operating effectively in time for the battle, during which 25 Coy was included in the final defensive positions behind No 3 airstrip. At the end of the year C Force became 11th Division, its AASC headquarters redesignated HQ 11 Div AASC with Lieut-Col J. Talbot taking over as CAASC, but it was shortly removed to Port Moresby garrison and replaced by 5th Division. Thereafter the units grew to HQ Comd AASC 5 Div, 2/6 Coy, 1 and 2 Sup Dep Pls with 27 Coy (later redesignated 154 GT Coy) replacing 2/2 Coy. Milne Bay Base sub-Area units were expanded to 3 BSD, a section of 1 Fd Bch Pl, 2/2 Fd Bakery, 2 Bulk Pet Storage Coy, 3 BIPOD and detachment of 3 Pack Tpt Coy. This extended occupation resulted in extensive construction of roadways, a light railway for the BIPOD, and storage and accommodation facilities which reached a reasonable standard at about the same time as the significance of the base waned in 1944 40.

A second enemy assault seemed imminent in April 1943 but was forestalled by the naval battle of the Bismarck Sea. The area had meanwhile become a mounting base for offensive operations. A small supplies detachment supported deployment of 2/12 Bn and subsequently US forces on Goodenough Island, and further afield port facilities were established for the seaward support of the counter-offensive through Kokoda which flowed through to the recapture of Gona-Buna-Sanananda. A forward base including 5 BSD and detachments of 2/106 GT Coy, 3 BIPOD and 2/2 Fd Bakery had been set up at Oro Bay in November 1942 to support both the airfields at Dobodura and the US 32nd Division's attempts on Buna; and after the latter's capture by 18th Brigade, a port was established, cleared by 151 GT Coy, to support operations against Salamaua and later Lae. These bases were taken over by 11th Division in August 1943 as it relieved 7th Division at Dobodura. Lieut-Col E.L. Smith became CAASC the following month, having at his disposal for the Dobodura-Buna-Oro Bay areas 2 Air Maint Coy, 2/106, 158, 162 and 165 GT Coys, 23, 31 and 34 Sup Dep Coys, 3, 53 and 54 BIPOD Pls, a detachment of 2/2Fd Bakery and 66 MAC Pl 41.

Before this the continuing thrust of 7th Division from Kokoda to the coast had slowed then stopped in bitter fighting at Gona and the Sanananda Track. Gona was taken lO-December 1942, Sanananda not until 14 January 1943. After the US 32 Division's failure at Buna, 18th Brigade from Milne Bay was brought in to finish the job by 2 January 1943; the price was the extinction of four brigades as a fighting force and their withdrawal to the Atherton Tableland for recuperation and rebuilding. These operations had continued to rely heavily on air support, which was progressively facilitated by establishment of the air base at Dobodura and increased availability of DC-3 aircraft; opening of coastwise support from Milne and Oro Bays also helped in the final stages against Buna and Sanananda 42. A new approach to resupply of forces had evolved from the Kokoda Track’s reactive, emergency nature of throwing in whatever could be found and using any and all expedients to maintain the forces involved. Thereafter geography still precluded any text book solutions and continued to demand initiative, expediency and use of all available resources and systems of supply and movement, but an operating pattern emerged which fitted the environment. Instead of the composite arrangement which was evolved for North Africa and Europe, the Tropical system accepted the almost total lack of roads and worked on a system of dumps from which delivery was made by truck, jeep, trailer train, air, water, animal and carrier transport.

The general grouping was therefore based on supply depot platoons to hold stocks and man dumps, and transport platoons for base and forward delivery work. To this was added air maintenance and pack transport units, with supply depot, transport and air maintenance company headquarters where required for control. Carrier lines were provided by ANGAU, riverine and coastwise transport by the Navy, RAE (Transportation) watercraft and AASC DUKWs. The spartan levels of support and reduced use of commodities and vehicle movement which were either required or possible in these operations had meant that a large part of divisional AASC units had no place and were employed in other areas on general tasks. This system was later to be recognised in the jungle division establishments with half the previous manpower, and employed with infinite variations to suit local requirements as operations moved on to retrieving New Guinea.

Reconquest of New Guinea

With recapture of the Buna-Gona area the strategic objective of securing Papua from use as a base against Australia was effected, and the next phase was to secure airfields for use in operations against Japanese forces in the Philippines and Rabaul. The first move in the reconquest of New Guinea was the attempted thrust from Wau to Salamaua to tie up enemy forces. A small raiding group called Kanga Force was based at Wau in the Eastern Highlands in April 1942 to operate against Lae and Salamaua, but its depredations drew a countermove by the Japanese to Mubo. This caused the force to destroy the facilities, stores and vehicles at Wau and Bulolo, unnecessarily as it turned out, exacerbating future maintenance problems, particularly with the priority given to the parallel operations on the Kokoda Track.

Although there were airstrips at Wau and Bulolo, it was decided to attempt an alternate water-road crossing by driving a road through the divide from the Lakekamu riverhead in the south to Wau on the north side of the range. AASC support was controlled by DADST Bulldog L of C Area who had detachments of 15 Sup Pers Coy and 2 BIPOD to support the southern base. Detachments of 1 and 3 Pack Tpt Coys, which became increasingly surplus as the Kokoda operation concluded, were allotted as part of the construction workforce. The route finally consisted of small ships from Port Moresby to Terapo, rivercraft to Grim Point, tramline to Bulldog, and vehicle to Wau via Edie creek. The first jeeps left Wau on 23 August 1942 and, a similar convoy left Bulldog the following day, with a potential capacity of 8 tons per day by jeep and a development potential of 250 tons per day if upgraded to 3 ton vehicle level. However capture of the port of Lae the following month rendered this route irrelevant. Authorised by Blamey in December 1942 for completion in April 1943 when it would have been valuable in operations from Wau to Mubo, Salamaua and Lae 43, its continuation up to the time of the capture of Lae was an expensive waste of effort, and an indication of the excessive resources which had accumulated in the Port Moresby area.

Wau-Bulolo Road

From 14 January 1943 17th Brigade Group began to fly into Wau to match Japanese reinforcement of the Huon Gulf area. The enemy's concern on the threat to Salamaua led to an attempt on Wau airfield, which was beaten off by flying troops in to the airfield in the thick of the battle. On the night of 29/30 January before these reinforcements arrived, when two resident battalions' covering positions had been broken, all available forces including the transport detachment were formed in a tight perimeter around the airfield lifeline, reinforcements flying in the following morning. But by 6 February the attack was broken and 17th Brigade took up the offensive towards Mubo. Resupply remained dependent on air landing at Wau and Bulolo, air dropping to forward positions, and carrier lines for collection and distribution of air drops, so air superiority became of paramount importance in maintaining the aerial lifeline. There was, however, some limited scope for jeep traffic on the roads in the Bulolo valley, and some of the civilian vehicles damaged in the previous year's scorched earth effort were recovered and put into operation. After a decision to threaten Salamaua to fix enemy forces there and so weaken Lae in preparation for its capture, Headquarters 3rd Division took over Kanga Force. Its buildup at Wau included an advanced HQ Comd 3 Div AASC under Lieut-Col L.C. Page, 1 Comp Pl of 2/2 Coy, detachment 152 GT Coy, 1 Sup Dep Coy, a section of 3 and all 4 Sup Dep Pl, and detachment 13 Fd Bking Pl; this was augmented as operations developed with 18 and 2/34 Sup Dep Pls. Rear HQ at Port Moresby controlled the remainder of the divisional AASC, sent forward reinforcements and assisted resupply movement 44.

When 15th Brigade arrived and entered the battle in early June there were two axes: Wau-Mubo-Komiatum and Bulolo-Misim-Bobdubi, with the additional liabilities of independent and other companies operating near the coast and along the Wampit River to the Markham at Nadzab, then a landing of 162nd (US) Regiment at Nassau Bay at the end of June. Maintenance of the units forward was based on FSDs and FADs resupplied by jeep towards Mubo and air drop at Missim, with forward deliveries by air drop and porter. The Markham area was supplied by air drop at Zenag, 3 Pack Tpt Coy delivering part of the way forward to carrier lines. All supplies were air lifted from Port Moresby until a trickle started to come over the Bulldog road in August, at which stage a partially successful attempt was made to release aircraft from air supply for the planned air assault at Nadzab, the eastern supply route switching largely to native carriers resupplied from watercraft landing at Tambu Bay after its capture by the US regiment. Rear HQ CAASC was established at Bulolo, with the forward HQ following the slow advance, and eventually transferring to Tambu. In this final phase DIDs located at an air dropping ground, with covered storage for supplies and ammunition, were established at Dobdubi for 15th Brigade and Komiatum for 29th Brigade (which had replaced the 17th), acting as bases for the final thrusts which captured Salamaua on 11 September 45.