Chapter 13

Colonial Wars

Nootka Expedition

The first colonial conflict involving Australia was a confrontation with Spain over fishing and trading on the North West coast of America. By the time of the Botany Bay settlement, skyrocketing whale oil and seal skin prices had launched a competitive scramble of British, United States and French vessels into the Pacific to exploit these resources, much to the anger of Spain which regarded the area as its own special province. Nootka Sound, on which Vancouver was later built, had a particular attraction in the sea otter pelts which Cook's last expedition had found highly saleable in Canton on the way home. As Britain was hard pressed to find the silver which the Chinese demanded as the currency for tea and silk purchases, this new currency sparked official interest in the area, regardless of Spanish protests 1.

Commissary John Palmer 1760-1833

Palmer, purser of the Sirius, was appointed Commissary General of New South Wales and a magistrate in 1791, replacing Andrew Miller.

After receiving a grant of land at Wooloomooloo, by 1795 he was described as ‘one of the three principal farmers in the Colony’; by 1803 he had pioneered efficient farming and owned locally-built trading boats, a windmill and bakery. He continued to grow his farming empire on the Hawkesbury, Bathurst and in the present Canberra area.

As Commissary he ran the government stores on which much of the colony depended, was effectively Treasurer, and by his authority to draw bills on the British Treasury, was the Colony’s banker.

He accused John Macarthur of corruption in relation to the government stores, and the pending trial accelerated the mutiny against Bligh. Palmer was imprisoned by the mutineers, and returned to England where his testimony led to conviction of the coup leader Major Johnston.

He returned to NSW in 1814 in the Commissariat, retiring in 1819. His daughter married into the Campbell family of Duntroon.

Commander George Vancouver 1758-1798

He accompanied James Cook as navigator on his second and third voyages of discovery (1772-74, 1776-80). He was subsequently given command of a naval expedition to Nootka Sound (now Vancouver) in 1791 to resolve the aborted war between Britain and Spain after the latter’s arrest of trading ships.

He accompanied James Cook as navigator on his second and third voyages of discovery (1772-74, 1776-80). He was subsequently given command of a naval expedition to Nootka Sound (now Vancouver) in 1791 to resolve the aborted war between Britain and Spain after the latter’s arrest of trading ships.

An instruction had been prepared for Philip to provide Sirius and military and logistic support was aborted by the loss of the ship at Norfolk Island. On his way to North America via the Cape, he noted King George’s Sound (now Albany) as a strategic asset. His support ship HMS Daedalus was resupplied at Sydney, bringing from Monterey in Mexico the first Merino sheep to the colony.

After a Spanish frigate arrested four British ships at Nootka in 1789 Britain decided to enforce its claims to what it now called New Albion by war 2, planning to include in the squadron HMS Sirius, whose loss at Norfolk Island was as yet unknown to the Admiralty 3. As part of this plan, instructions were prepared for Governor Phillip to provide sailors, settlers and logistic support to confront the Spanish at Nootka and establish a military colony there. As a waning maritime power, Spain backed down, conceding freedom of navigation and fishing in the Pacific, with restoration and reparation for their actions at Nootka. The original offensive plan was therefore replaced with an expedition under Captain George Vancouver to reclaim custody of Nootka from the Spanish, survey the area and test the freedom of passage. Phillip received instructions to provide him with supplies then and as he might subsequently require 4. The Commissariat in NSW at the time was in some trouble to support its own Colony, however Commissary John Palmer was able to meet the requirement adequately in 1793 when the stores ship HMS Daedalus arrived in Port Jackson for replenishment. Vancouver expressed his appreciation of the assistance and, in Phillip's absence, Acting Governor Grose was able to advise London of having 'the satisfaction to send him from this place almost every article he has asked for' 5. This use of the fledgling Colony of New South Wales as a military supply base seems strange only if the misconception of its being simply a prison farm is accepted. It was, in reality, one of a chain of military colonies strung across Britain's trade routes at the end of the 1780s from Sierra Leone to Botany Bay, and now to Vancouver. The support functions which were required of it under the two plans were no more than the mission of the colony allowed, as was signified by the fulfilment of the tasks without comment – the Commissariat's responsibility was to meet the demands and replenish itself, using the Military Chest, from whatever sources it could. The support of visiting naval forces also continued as a routine of the Commissariat's tasks, but it would to be another 55 years before it was necessary to mount a significant military expedition from Australia.

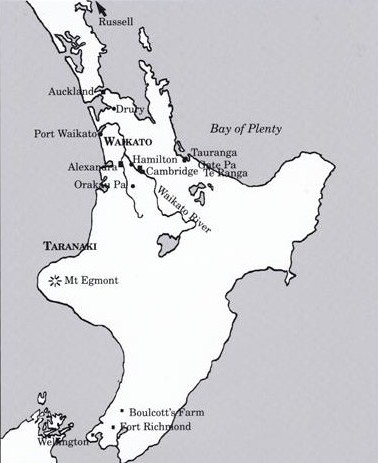

Maori Wars

In acceding to the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, those of the Maori peoples who signed imagined they were accepting British protection rather than exploitation. That exploitation was occurring Colonial Secretary Earl Grey recognised belatedly in 1847 – that the land-hungry settlers were using the technique of provoking Maori attack, calling in the Imperial troops, then picking up the land so liberated afterwards. Chief Heke's persistence throughout 1844 and early 1845 in cutting down of the flagpole in the township of Russell, which he had earlier erected as a symbol of friendship but now regarded as symbolising foreign domination, led to requests for troops. Australian Command progressively sent detachments which built up to 600 and as well Deputy Assistant Commissary General Turner was dispatched with a Commissariat cadre to provide supply and transport support, with Sydney as the main base 6. The executive functions of the Commissariat were essentially carried out by contracting grocers and hauliers, but it is interesting to see the spirit of getting support through at any cost permeating even to them. During a Maori assault on the post at Boulcott's Farm, John Cudby, engaged in carting Commissariat supplies from Wellington to the garrison, set out as usual, unaware of the action. He had initially been given a daily escort of 15 soldiers from Fort Richmond but 'the poor fellows in the stockade were worked to death, and so I said I'd do without them in future' and he now had only the military issuer riding shotgun. The fleeing occupants of a cart called out to Cudby to turn back, to which he replied 'I dursent go back – I've got the rations to deliver', drove on into the camp and assisted with the casualties 7.

Lack of infrastructure and the ad hoc nature of commissariat operations led to constant problems which had not been properly solved by the end of the emergency in 1848. However, while constantly plagued by shortages, inadequate resources, and neglect of commanders to make sufficient administrative provision in their plans, the supply and transport support of operations was generally adequate. This small scale introduction to the colony laid a useful base for later larger scale and more sustained operations.

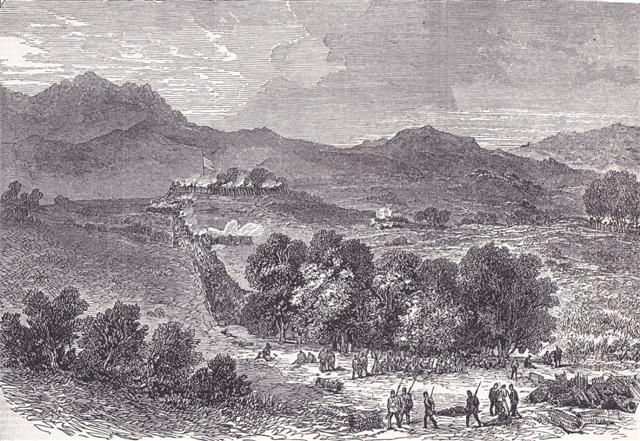

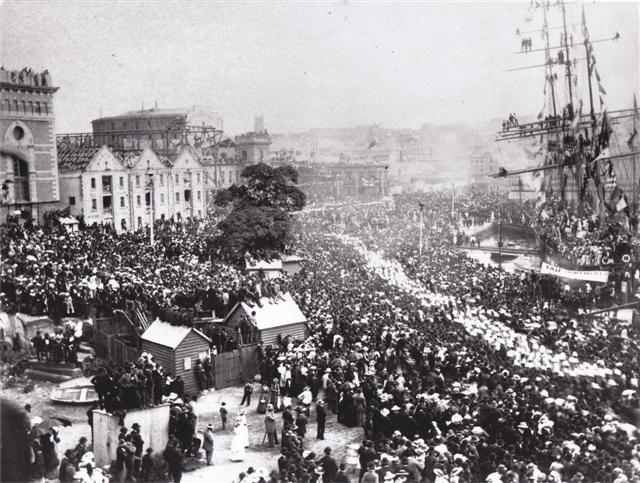

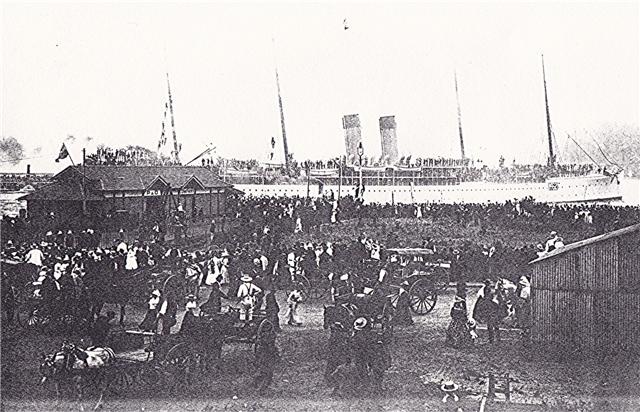

Continuing colonial intransigence and Maori reaction led inevitably to a revolt in Taranaki 1860-61, then a full scale war in 1863, when the settlers withdrew to Auckland and the Maoris retired to the Waikato area with carefully built up stores of arms and ammunition, much of it smuggled in by American whalers 8. Governor Sir George Grey's military solution required reinforcements from the Imperial regiments and Commissariat in Australia, and militia mainly for protection and logistics duties. The local settlers were well accustomed to letting others fight for them, so it became necessary to recruit men from Australia, often stated as from the goldfields, however this oversimplification is rebutted by the records of origins and occupations which are available. The first 553 were absorbed into the Taranaki Volunteers but in 1863 and 1864 major recruiting drives for the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Waikato Regiments, commonly called the Waikato Militia, brought the total of Australians to 2,368. The lures were a patriotic call to service and 'rich Waikato land' – a town allotment of one acre plus a farm allotment ranging from 50 acres for a private to 200 acres for a field officer, resellable after completion of the three-year engagement 9.

War in the Waikato was heavily dependent on the lines of communication. Although a military road had been put in from Drury to the Waikato River, from there forward the waterway was the most efficient and secure route. A fleet of eight river steamers formed the backbone of the supply line, but shallows and rapids required a leg which was covered by flat bottomed boats rowed by eight or twelve oarsmen and another where the boats were towed by horses on the bank. In addition, land transport was needed throughout the system, being a mixture of horse and bullock wagons. When the front extended to the south of the valley, twelve to fourteen trans-shipments were required between Auckland and the operational area. An expanding Commissariat Department and a Transport Corps were needed to operate depots, workshops and riverine, wagon, dray and pack transport, operating in distinct groups. The Commissariat Department under Deputy Commissary General Jones operated the base from a depot at Port Waikato, receiving meat and groceries from local contractors and the remainder direct from the Commissariat Stores in Sydney. Also established at the port were repair facilities for anything from river steamers to wagons and harness. The Commissariat Transport Corps under AQMG Lt-CoI D.J. Gamble provided field transport and distribution, comprising a Land Transport Corps and a Water Transport Corps, building up to a peak of 13 companies of 1,526 men and 2,244 draught animals. The cost was high, involving 40 percent of the force in supply and escort duties, but its influence on the success of the campaign was significant, due in no little part to the ingenuity and effort which was sustained throughout. Although there were continual problems due to the tenuousness of supply sources and primitive state of communications, accentuated by looting of stocks by the sailors during transit, the overall organisation was so successful that, when the 4th Battalion of the Military Train arrived in the country from Ireland at the end of 1863, it was used for base duties in Auckland, then as cavalry, to avoid disruption to the existing supply and transport system 10.

Commissariat Department and Transport Corps were built up from volunteers from the regular and militia regiments. They included a heavy component of members of the Australian contingents of the Waikato Regiment however the actual number involved is difficult to ascertain as they clung tenaciously to their regimental identification, to which the land grant and benefits attached; those who relinquished that affiliation for other volunteer units before the expiration of the three year engagement were still petitioning for their land a decade later. From the available records about 300, comprised of 25 in the Commissariat Department and 275 in the Commissariat Transport Corps, were awarded the New Zealand Medal for operational service, but inconsistencies in those records makes this figure provisional. Employments of the military members encompassed: supervisors of land and water transport, driver, bullock driver, coxswain, boatman, clerk, storekeeper, issuer, butcher, baker, artificer and labourer. Two were Lieutenants J.T. Fraser and H.B. Lomax – the former nicknamed Bully for his aggressive approach, the latter remembered mainly for his tall tales and true. Of greater repute was Lt G. Raynor who was entrusted with reconnoitring the upper Waikato, which he executed through enemy-held territory in two boats with muffled oars. Lt F.Y. Goring joined the Victoria-raised Pitt's Militia contingent of the Waikato Regiment and from early 1864 spent two years with the Transport Corps as a captain, returning to the Regiment until it was disbanded in 1867, receiving field promotion to major, then transferring to the Armed Constabulary 11.

The last battle of the Waikato campaign which finally broke organised resistance was fought at Orakau Pa near the head of the valley from 31 March to 2 April 1864. In support of the advanced force which had surrounded and attacked the fort was Capt W.V. Herford, an Adelaide barrister who had raised a company of 300 for 3rd Waikato Regiment in the second Australian contingent, and after arrival in New Zealand had transferred to the Transport Corps. After the first assault was repulsed, Herford applied to join the fight and, with Lt H.B.R. Harrison and some drivers of his transport detachment, covered the forward edge of the sap which was driven towards the fortifications during the second day, keeping the defenders under continuous fire. During the night the Maoris made a sally to stop the work and were repulsed by Herford's party. On the third day, with the sap close to the fortifications and the defenders having refused to surrender, one of diggers threw his cap into the fort and jumped over the palisade after it, followed by Herford leading a mixed group of 20 including Harrison, the drivers, Forest Rangers and regulars. After they had burst through the palisade into the first trench and were trying to climb the next embankment, half were cut down by a hail of fire from above, including Herford with three of his men killed - Cpl J.A. Armstrong, Pte J. Leeky and Pte J. Lovett – and three others wounded; but the ferocity of their attack had pushed the defenders back and the survivors were able to extricate the casualties. The breach had been made so the Forest Rangers in strength broke into the pa and it was quickly taken. Herford survived his apparently fatal head wound, losing an eye; he continued on in the Transport Corps, promoted to major, only to collapse and die the following year from the bullet lodged at the base of his brain. Herford and Harrison were both mentioned in the commander's dispatches for bravery 12.

Map 4: North Island of New Zealand, 1845-72

While the campaign in the Waikato was mainly completed within a year, others followed at Gate Pa, Te Ranga and Tauranga in the east, and south to Mt Egmont; the Transport Corps continued in support, its Waikato Regiment volunteers remaining a component of the transport companies. But as the fighting progressed, the manoeuverings of the politicians and settlers became more obvious: the military victors, particularly those who did not acquire large estates as a result, were less than enthusiastic on the purpose of the war which became more and more obvious as land plunder subsidised by the imperial Treasury, as much as local contemporary politicians, press and literature protested otherwise. The Waikato Regiments and other volunteers were quickly settled on confiscated land at Tauranga, Alexandra, Cambridge and Hamilton to relieve the colony of the cost of paying them – as military colonists their protective screening value was retained for the guerrilla warfare which followed, and they could be called out for operations later and paid for them only when this was a necessity. The regiments were disbanded in 1867 after the three year engagements expired, those who wished to remain in service being absorbed into the 4th Battalion Auckland Militia; others who had been caught up in the 'serve the Queen' recruiting drive, and were now either disillusioned, or unable to support the costs of establishing their farms without active duty militia pay, disposed of their land. Those with the Commissariat Department and Transport Corps tended to be kept on duty for extended periods as the sporadic fighting continued up to 1872, and consequently having an ongoing income to finance development of their farms, remained in what became New Zealand's most expensive agricultural land; today many families claim descent from those militiamen from Australia 13.

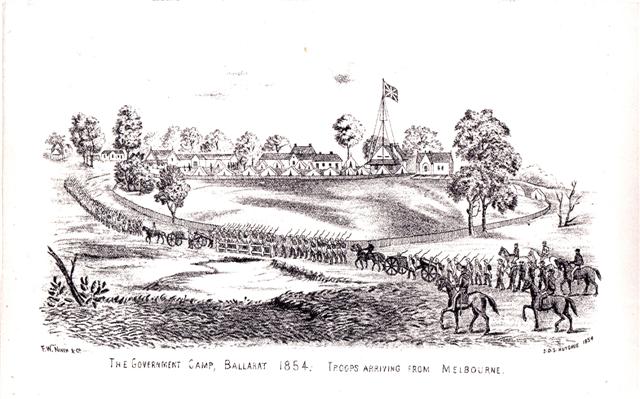

Eureka

Between the phases of fighting in New Zealand, Imperial and Colonial forces faced each other in an engagement in the Colony of Victoria. Growing discontent in the mining communities on the harshness of implementation of the mining licence regulations, associated with withholding of the franchise and locking up of the land by squatters, culminated in a confrontation between administration and miners at the Ballaarat goldfield. Escalating incidents and provocations on both sides, compounded by a desire of Lieutenant Governor Hotham and conservative elements to withstand democratic pressures and make an example for law and order, culminated in a successful surprise dawn assault, on Sunday 3 December 1854, by part of the 40th Regiment and police on about 120 miners manning a defensive stockade on Eureka Hill. While some hardheads today still try to brand the reformists as treasonous revolutionaries, the facts speak for themselves. They were subsequently granted their demands after a Commission had investigated the affair, the 13 men sent for trial were acquitted of treason charges, and leader Peter Lalor became a member and Speaker of the Legislative Assembly 14.

The Imperial force at the diggings was built up to about 600; at the time of the attack an equal number of reinforcements was on the way from Melbourne, headed by the commander of the Australian command, Maj Gen Sir Robert Nickle who 15 had recently relocated his headquarters from Sydney, motivated largely by his inability to find suitable housing for himself in that town. The commissariat headquarters under Deputy Commissary General F.T. Coxworthy had accompanied this move, with local representative at Ballaarat Deputy Assistant Commissary General Bower controlling supply and transport for the forces there 16. This move had been a significant upgrading for Victoria's Commissariat as even after separation in 1851 it had still been part of the NSW structure, unlike the other smaller colonies which had semi-autonomous commissariats dealing directly with London. The scope of the Commissariat in Port Phillip District and then Victoria, not having a convict establishment, had been limited to support no more than a company sized detachment until the build up of forces from 1852 after discovery of gold, and subsequent transfer of its headquarters from Sydney.

The militant wing of the Ballaarat Reform League, which reached a maximum of 1,500, had little enough logistic support, sending 'out parties to collect arms, ammunition and commissariat supplies'. They bought bread and meat from the local butchery and bakeries and collected weapons and ammunition where they could, on a goldfields so peaceable that it was no longer necessary to have arms; the result was that the 120 manning the Stockade at the time of the assault had about 100 firearms and a few rounds for each, the remainder armed with pikes forged on site. Support which was provided by the imperial Commissariat for the forces at and moving to the goldfields was not much less basic. In the siege-minded military camp at Ballaarat were stocks of food, forage, ammunition and water; supplies and transport were procured locally as necessary; and supplies and ammunition from Melbourne were moved by hired wagons, some of which belonging to George Young carrying ammunition and baggage were attacked by diggers as they passed the stockade under escort 17. After the attack on the stockade, casualties were cleared in hired carts, and the prisoners were also dispatched under escort to Melbourne gaol by this means 18. However this was not unusual. Not only were the regiments in Australia not organised for field operations, but at that very time the British Army in the Crimea was suffering from the same problems of ad hockery, resulting in a political storm which led first to the formation of a Hospital Conveyance Corps for casualty evacuation, then the Land Transport Corps for field supply and transport. The smallness and brevity of the operation at Ballaarat saved any like catastrophe for the Imperial force; ineffectual resources on the Colonials’ side precluded any effectual resistance.

Suakin Expedition

At the beginning of 1885 the collapse of Egyptian resistance in the Soudan against a jihad led by Mahdi Mohammed Achmed, and a consequent threat to Egypt and the Suez Canal, provoked a spontaneous offer of troops by the Colony of New South Wales, closely followed by similar ones from Queensland, Victoria and South Australia. The British Government accepted the New South Wales offer with some alacrity, probably all the more so as Prime Minister Gladstone was desperate to stave off mounting pressure on his government over its apparent abandonment of Maj Gen 'Chinese' Gordon in Khartoum. The offers by the other colonies were not proceeded with in order to avoid delays to the dispatch of the force, and rapid action by the New South Wales Government, supported by public patriotic fervour, saw a contingent of 766 – a headquarters staff, infantry battalion, field battery and an ambulance corps – recruited, formed, equipped and embarked within three weeks 19.

New South Wales was at first anxious to provide adequate administrative support and supplies for its force, but the difficulties of transporting wagons and horses, together with a precedent-setting unwillingness to reduce the numbers of combat troops to make way for support personnel, militated against the raising of a commissariat and transport corps. The NSW Government therefore requested that the British forces provide distribution of stores and forage and transport of the Force within the theatre of operations; in response, the War Office agreed on regimental transport, forage, rations and conveyance of supplies. In consequence, supply and transport representation in the Contingent was restricted to Paymaster and Commissariat Officer Maj J.T. Blanchard and Commissary Clerk WO H. Brodie 20.

The Contingent arrived at Suakin on 29 March 1885, was incorporated into Suakin Field Force and deployed on operations immediately. The campaign itself provided 'a few skirmishes ... much sweat and little glory'. Supply and transport support for the Contingent was arranged by its Commissariat Staff from the British Commissariat and Transport Corps units and their supporting mule and camel transport units from the Commissariat and Transport Department of the Indian Army 21. The Suakin expedition was terminated in mid-May with the Contingent withdrawn on 17 May 1885, returning to the same public enthusiasm which witnessed its departure 22. But small as the scale and role of the Contingent was, it set the pattern for the future: of Australia providing combat elements as part of British or allied forces, with those forces providing the framework of the Australian contingent's logistic support. The difficulties in logistics which were encountered by the supporting British organisation at Suakin might also have read a lesson on the need to have an experienced field force supply and transport corps for the NSW Military Forces: this lesson was not taken.

Boer War

The declaration of war by the Boer provinces in South Africa on 11 October 1899 was treated less than seriously in the United Kingdom, with expectations of 'over by Christmas'. When this misconception of the capabilities of both sides was shattered by the early 'Black Week' reverses, offers of assistance to the imperial side poured in from Canada, New Zealand and all the Australian Colonies 23; the latter sent in all 57 contingents to South Africa, totalling 16,463 men and 16,357 horses 24. Although an initial conference of Colonial Commandants had recommended the dispatch of a first Australian contingent of 2,000, to be a balanced group of all branches, this proposal was subverted by misinterpretation of a request from the War Office for a predominance of mounted infantry to match the Boer superiority in that arm.

In consequence the idea of a combined group faltered, resulting in fragmented colony contingents of mounted infantry and cavalry, infantry and artillery, with chaplaincy, veterinary and medical support 25. This more than suited the British perception, carried over to later wars, of the colonies providing combat units to be integrated into British formations as units and sub-units, relying for their command, combat, combat service and administrative direction and support from the Imperial forces and the infrastructure which had been established for them. The decision to limit the Colonial (and subsequently Commonwealth) contingents to fighting groups which were integrated into British columns provided an economical alternative to the problems of organising a unified and balanced force, and this was entirely logical from the Imperial viewpoint which had no concept of there being an Australian national feeling; there was barely any such notion in the colonial and then state contingents. The fact that the colonies' defence forces were heavily deficient in expertise in field force technical arms also discouraged any serious subsequent efforts to expand the scope of the contingents 26.

Although the contingents remained as combat units, the opportunity for specialist experience was not altogether lost. Individuals classed as Special Service Officers were either allowed to go to South Africa at their own expense or dispatched as official members of the Imperial force. On arrival they were attached to British or Colonial units or staffs in either a supernumerary or establishment position; the majority served with distinction. In addition, members of the NSW and Victorian Army Service Corps joined the line units or the reinforcement drafts proceeding to South Africa 27. Two officers of the NSW Army Service Corps served with the NSW Imperial Bushmen. Maj D. Miller, the Officer Commanding NSW ASC, was offered command of an Army Service Corps unit after he arrived in South Africa, but preferred to stay in action with his regiment. The other, Lt (later Capt) D.F. Miller was severely wounded whilst with the same unit, and died subsequently when serving with the 3rd NSW Mounted Rifles. Two other NSW ASC officers serving with 1st NSW Mounted Rifles, Lt C.O. Basche and Lt W.R. Harriot died on active service 28. The first Victorian contingent included an officer and a bugler from the Victorian ASC; as the column showing previous service was deleted from subsequent contingent rolls, the number of later volunteers is unknown, but the South African medals worn by Corps members in later photographs indicates that some others did serve there. NSW records are similarly incomplete, but by late 1900 four officers and 29 other ranks of the NSW ASC had served with mounted infantry units in the war 29.

A Victorian ASC officer on special service, Lt (later Capt) A.J. Christie, commanded P Tpt Coy ASC in operations throughout the theatre, being twice wounded, evacuated to England after the first and returning to South Africa for duty. A NSW artillery officer on special service, Capt A.P. Luscombe, commanded 33 Coy ASC, operating ox wagon convoys of up to 300 in support of operations in the northern mobile operations. His reports contain interesting insight to the ad hoc but effective methods of operation: a 101 wagon convoy with 1,621 oxen was driven with 230 conductors, porters and natives, managed by himself, a subaltern and 20 sergeants and rank and file. Losses of oxen were made good by rounding up cattle from the veldt under sniper fire 30.

Whilst no Colonial or Commonwealth ASC units were committed to the war, it amply demonstrated three vital lessons: the Australian colonial forces had made little provision for field force supply and transport units in their home structure; such units are of critical importance in fluid operations; and the expertise to provide those units cannot be assembled at short notice as was the mounted infantry. These matters were noticed by an Imperial officer serving in South Africa who also had under command some of the colonial contingents. He had reason to do so as a previous commandant of the NSW forces. Maj Gen E.T.H. Hutton also had the opportunity to do something about it when he became the first General Officer Commanding the Australian Defence Forces in 1902 and, as noted in Chapter 2, was an unqualified supporter of an effective field force Army Service Corps.

Footnotes

1. Marshall J.S. & C. Adventure in Two Hemispheres p56-7, 188, 193.

3. HRNSW 1.2 Grenville to Phillip March 1790, p312; as no record of date, dispatch or receipt is extant, this was probably a draft plan overtaken by events.

4. HRNSW 1.2 Grenville to Admiralty 11 February 1791, p451-2; Dundas to Phillip 5 July 1791, p497.

5. HRNSW 1.2 Vancouver to Phillip 12 October 1792, p667-8; HRA 1.1 Phillip to Nepean 29 March 1792, p345-6; Grose to Dundas 21 April 1793, p428.

6. Cowan J. The New Zealand War and, the Pioneering Period vol I, p16-18, 29; HRA 1.25 Grey to Fitzroy 30 November 1846, p279.

8. Fishburn J.F. 'Some Aspects of the Anglo-Maori Wars' AAJ March 1976, p33, 35.

9. Featon J. The Waikato War p51-2; Fishburn, p37; Barton L.L. Australians in the Waikato War 1863-64 p12-14,52; Holt E. The Strangest War p192.

10. Featon. p68; Fishburn, p40; Fortescue RASC 169-70; Alexander J.E. Bush Fighting p129; Cowan, p237.

11. Ryan & Parham, p106; Gudgeon T.W. The Defenders of New Zealand p354 and Addenda; Featon, p69, 85-6; Fortescue RASC p170; Crew RASC p52; Barton, p53-97.

12. Gudgeon, p84, 109-10; Featon, p81-2, 85.

13. Fishburn, p44; Holt, p199-200; Featon, p97; Ryan & Parham, p142; Glen, p88, 90-94.

14. Molony J. Eureka p202-7; Carboni R. The Eureka Stockade p.81.

16. Army List 1855; V&P Vic LC 1856 Ballaarat Riots Expenses of Troops and Police, p3-5 Bower expenses.

17. Illustrated Australian News 11 August 1888, p9; Molony, p120, 149, 151, 153, 156, 158; Carboni, p79, 80, 96; V&P Vic LC 1856 Expenses, p3-6. Note the error in the accounts facsimile, reproduced in this book, in the statement of wagon transport costs, where G. Young's second hiring is shown as 2 November, when it was for his wagons which were involved in the attack by diggers on the convoy on 2 December, the night before the capture of the Stockade.

19. Sutton R. Soldiers of the Queen. War in the Soudan p8-9, 42, 51-2.

23. Firkins, p6; Pakenham T. The Boer War p247-9; Sutton R. For Queen and Empire – A Boer War Chronicle p18.

24. Murray P.L. Official Records of the Australian Military Contingents to the War in South Africa 1899-1902, p206, 337, 342, 441, 542, 577-8.

25. V&P NSW LA 1901 vol III, First and Other Contingents to South Africa – Conference of Military Commandants 29 September 1899, p57.

26. As an indication, see annual reports of the commandants of the colonial forces in the Proceedings of the legislative assemblies of the colonies for 1900.

28. Murray, p87; Australian War Memorial AWM 1 565/5/2 Special Service Officers, Miller Report; Murray, p60, 62, 64.

29. V&P NSW LA 1900 vol IV French Report, p5; AA MP744/44 B5177.