Chapter 5

End of an Era

In 1964 the Mcleod Committee Report recommended to the British Government that some far-reaching administrative changes be made to the British Defence Forces. It included proposals to centralise almost all of the supply functions within the Royal Army Ordnance Corps and form a new Royal Corps of Transport to cover all Army movement and transport functions; the Royal Army Service Corps was consequently to be disbanded 1. This was implemented by mid-1968 and, as the Australian Army had not, in recent years at least, been notable for originality of thought on structural matters, the writing was also on the wall for the RAASC. A few years stay of execution was gained by the Army's preoccupation with the Vietnam War, however the run down of this commitment allowed a return to the favourite and usual activity of reorganisation. The Hassett Report of 1971, predictably, virtually mirrored the McLeod recommendations in relation to the Royal Australian Army Service Corps 2. This was accepted and was formally implemented on 1 June 1973.

Much of the reaction to the disbandment was based on sentiment and dislike of change to the status quo. Yet corps are formed by armies to fulfil a particular need, as long as that need exists. In earlier times the raising and subsequent disbandment of corps was commonplace, as is witnessed not only by such obviously short lived Australian based expedients as the New South Wales Corps, the Volunteer Automobile Corps and the Coronation Corps, but also the British predecessors to the Army Service Corps which were raised for campaigns and terminated afterwards. However the Australian Army, at least, had come to regard corps as institutions, particularly after they spread from being executive agencies, equivalent to units or regiments, into the staff structure, so gaining a top-to-bottom patronage system and a life of their own. In a small army which, outside the infantry and light horse, lacked any real unit continuity, they made up for a lack of regimental tradition and esprit, becoming a fixed part of life especially for the supporting arms of the service. In consequence the restructuring was regarded largely as an infringement on a 'right' rather than in the real context – have these corps outlived their utility to the Army? This very valid question was lost in the deficiencies of the decision making process mentioned previously, compounding the natural problem of overcoming traditional resistance.

Apart from these general early feelings, the decision to disband the Corps resulted in a wide range of reactions. Those whose limited horizons stopped at trucks or air dispatch were exuberant. Those entrenched in the supplies and POL areas were depressed at going from a service-at-any-cost environment to the reputedly far different one in the Ordnance Corps. The thinking ones were greatly concerned at the potential for degradation of support to the field army, as no coherent substitute for the supplies and transport system was planned or even considered as part of the decisions to change. Indeed, it was not until mid 1976 – four years later – that, after nearly a year of discussion and bickering, a Department of Defence (Army Office) working party produced a still-disputed recommendation to the Chief of Operations John Williamson which resulted in the issue of a policy statement directing that the new RAAOC combat supplies platoons (rations, POL, ammunition) would operate with and under the control of RACT divisional transport 4.Adverse feelings also pervaded many members of the Royal Australian Engineers (Movements and Transportation) who were to become part of the new Royal Australian Corps of Transport – convinced that they were to become an unequal partner in the new organisation. Such feelings were echoed by many of the RAASC contingent to RACT who believed that the influence of the initially dominating contingent of senior officers from RAE would lead to bias in that direction. This feeling persisted until a new generation arose which both knew not of these prejudices, and could not be bothered with the supposed wrongs claimed by their predecessors. How this eventuated, however, belongs to the story of the RACT.

The lead up to the disbandment of RAASC was also a period of run-down of the Army in general, which was felt equally by the Corps. The Vietnam era had ended; the incoming federal government had directed withdrawal from ANZUK Force and the suspension of National Service. Both Regular and Citizen Forces units were reduced to mere shells and morale plummeted. And in addition to the corps reorganisations, a general restructuring of the command system proposed in the Hassett Report was also being implemented 5. This change from geographic to functional command removed the one rock of stability on which the Army had usually been able to depend in times of reorganisation. Turmoil was almost complete, but perhaps it was as well that all these changes came at the one time, debilitating as they were. Rebuilding was able to take on a very positive prospect – there was only one way to go, and that was upwards.

At the beginning of 1972, six months prior to completion date, the movements and removals staff functions at Command headquarters came under control of the previous Supplies and Transport Staffs, now named Transport and Movement Staffs and headed by a Chief Transport Officer replacing the CRASCs and DADSTs. Simultaneously Supplies and POL staffs joined the Ordnance Services staffs, with the base supplies units and staff clerks under their management. At Army Headquarters the previous year, as an interim arrangement, the rump of DST which had not gone to the new Directorate of Supply, plus the Directorate of Transportation and the Directorate of Movement, were amalgamated under a Director of Transport with two sections – Movement and Transport. In the following functional reorganisation of the Army command system, this was split into a separate Directorate of Movements at Army Headquarters and a Directorate of Transport in Logistic Command, in defiance of the much heralded intentions of amalgamating all transportation functions, and the much lauded benefits of doing so.

Discarding the title RAASC itself did not have a smooth passage. During Military Board discussions the Deputy Chief of the General Staff and the Master General of Ordnance, both aware of the value of corps esprit and the continuity which made it, opposed the change to RACT, in that it too thoughtlessly followed the British path, and was anyway inconsistent with the parallel proposal to allow RAAOC and RAEME to retain traditional names which did not necessarily describe their corps functions. This issue was deferred pending seeking an opinion on general acceptability within RAASC, and the change to RACT was approved at a subsequent meeting only after the Military Board was assured that it 'was strongly supported by the Head of Corps and the members of the Corps' 6. The change was finally approved with the DCGS and CMF Member still unconvinced, perhaps having been fed alternative feelings within the Corps than were laid before the Board.

There was much confusion in unit and staff organisations. The upcoming functional commands – Field Force, Logistic and Training Commands - were to supplant the geographic ones, which latter were to be partly replaced by military districts responsible only for local administration 7. This breach of the principle of unity of command was to have serious lasting effects on the command and administrative system; in the smaller districts it was almost immediately reversed by making the district commander responsible for all functions, but Queensland, NSW and Victoria had to persist in a costly and disruptive exercise, which has since been gradually modified back towards the geographic basis that is inescapably the way that a terrestrial service operates. Under this functional command system it became necessary to insert intermediate headquarters in each of the districts to administer and control the logistics units. The title of the movement and transport headquarters in this plan was the subject of much fuzzy thinking, with the original establishments showing RACT Queensland, RACT NSW etc, which were hardly unit designations. After active intervention by the victims through the General Staff net, the titles 1st Transport and Movement Group etc were adopted, the Chief Transport Officer designation giving way to Chief Transport and Movement Officer to better define the real function. These groups were officially formed on 1 June 1973, after which all base and field force units were also redesignated as transport units and companies, later squadrons or regiments as appropriate. The RAASC was disbanded and the RACT formed.

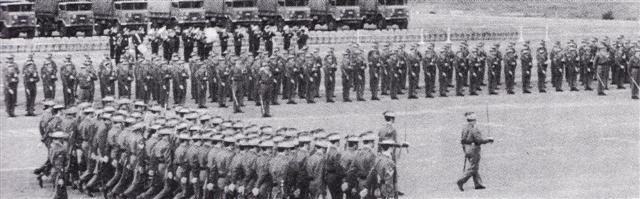

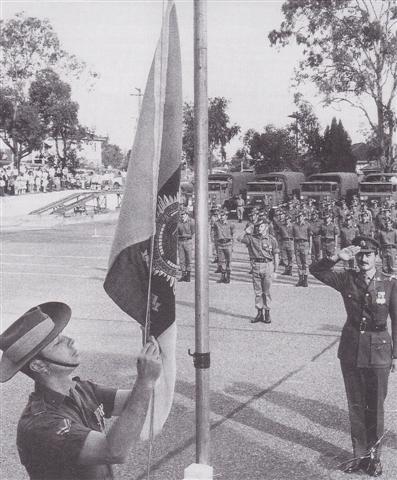

Various ceremonies were held in all main military centres in Australia and in Singapore to mark the dissolution of the Royal Australian Army Service Corps, the transfer of the supplies, POL and staff clerk component to RAAOC, and the consolidation of the existing transport, postal, transportation, removals and movement staffs and units into the new Royal Australian Corps of Transport. Similar ceremonies were held by RAAOC to welcome aboard the incoming supply components from RAASC, RAE and RAAMC. These were occasions of many mixed feelings, some of which were enunciated earlier. There was an element of sadness for the demise of the RAASC. It had served its function well, and by and large its members were proud to belong to it. The future in an unknown corps was less than certain.

This uncertainty came to the heart of what a corps is really about. Its early function, as alluded to previously, was to fulfil a specific operative function. When a new functional grouping was raised to execute a particular activity, it had, in military fashion, to be called something designating it as a formed body under military command – witness the modern reaction against a sloppy title such as the initially-proposed RACT NSW etc. A disparate group like the Coronation Contingent of 1911, the Fortress Engineers or the collection of grocers and drivers which constituted the colonial ASCs, could not fit into the image of the titles battalion or regiment used for combat units, so the collective name corps was used to handle such groups. Indeed, in recent times in Australia, the word unit itself would in aII probability be used, but a century ago corps was the catchall for an unusual unit. This concept of corps being executive units underwent a complete change as they grew and changed shape; in the middle of World War 2 AASC numbered over 50,000 men in over 600 units, with substantial staffs at all levels, and was the second largest corps in the Army after Infantry, as it was again during the Vietnam war. Its early unit character had changed to an agglomeration of functions, units, staffs and individuals rather than a function carried out by the Corps as a discrete executive body. Along with other corps, and particularly those covering the logistics services, it came to be a group which also encompassed the functions of patronage, unionism, brotherhood and self-defence mechanism. Many of these qualities are of negative value to the Army's general interest, but there is just one positive quality which stands out in the modern army. It is possible to describe and execute any function in today's Army without mentioning or needing a corps, except for this one thing: esprit de corps for organisations not firmly rooted in the continuity of a strong regimental structure.

It was this very positive reason which provoked the sadness, regret and uncertainty accompanying the end of RAASC. The receiving corps – old and new – were unknowns, with the RACT yet without any of the corps spirit and traditions which are about all that a modern corps has to offer. Those transferring to RAAOC at least had a respectable old family to join, but the several RACT contingents had a new family to build. However in this there were some positive factors: the British RCT had shown over the previous years that this spirit could be built up quickly and that residual prejudices could be overcome or left behind; the traditions and spirit of the RAASC and RAE were there to be carried on; and there was also a challenge to build something new and purposeful. The old Corps went with a sad tribute to an old friend; the story of the new belongs to a subsequent volume of this history.

Footnotes

2. Hassett F.G. et al eds Report of the Army Review Committee p55.

3. The period included restructuring of the Defence and Service Departments, on which Secretary of Defence Sir Arthur Tange commented 'I have restructured the Department to facilitate peacetime administration' (on question following an address at Australian Joint Services Staff College 17 July 1975).

4. COPS-A minute of August 1976.

6. Military Board Minutes 52/197l, 447/197I.

7. Hassett Report, p29; whilst it might be gratuitous to say that from the title ‘Logistic’ the originators couldn't even spell Logistics, their comprehension of the subject must be open to serious question.