Chapter 4

War and Reorganisation

Impact of World War 2

Australia entered World War 2 with a Permanent army component comprising a Staff Corps, Instructional Corps, Darwin Mobile Force (of 230) and administrative elements, adding up to something over 3,500. The Citizen Forces of the Army amounted to four infantry divisions and independent brigade components of a fifth, two cavalry divisions and some supporting troops, all under strength, totalling 80,000; AASC's complement was fifteen supply and ammunition companies 1. As the Defence Act precluded service outside Australian territory by the Citizen Forces, and as the Government soon committed troops to the British Government for such employment, thoughts naturally turned to the successful formula of World War 1, even though the Citizen Force was itself modelled on that basis in expectation of being the force to volunteer and be used. A volunteer second Australian Imperial Force was raised to meet the same initial concept of a 20,000 man contingent as was made in August 1914, except that it was not necessarily to be dispatched overseas. Recruiting results were not the flood which occurred in response to that previous call to arms, primarily because it had already been largely tapped by Blamey's recruiting drive for the Citizen Forces over the previous year, and the members of those Forces, not convinced that the AIF contingent would be the one to actually go overseas, mostly preferred to stay with their units in expectation of volunteering en bloc 2.

Raising of the 2nd AIF followed a similar initial pattern for the AASC as had that of the earlier model. Some units were familiar, others not so. Instant mechanisation was facilitated by a reasonable sprinkling of licenced drivers culled from the volunteers. Formation of the initial expeditionary force saw the raising of HQ AASC 6 Div, 6 Div Sup Coln, 6 Div Petrol Coy and 6 Div Amn Coy 3, on the commodity system rather than the flexible divisional composite companies which had been so successful in World War 2 that even the corps troops units had eventually followed that model. The general reluctance to join this force from those in the regiments and battalions in the Militia was less pronounced in AASC circles as there was less affiliation, with smaller, scattered units in which the usual fiddling with unit titles between wars had eliminated real bond or tradition, so there was a strong surge to fill the new units from both Militia and new volunteers.

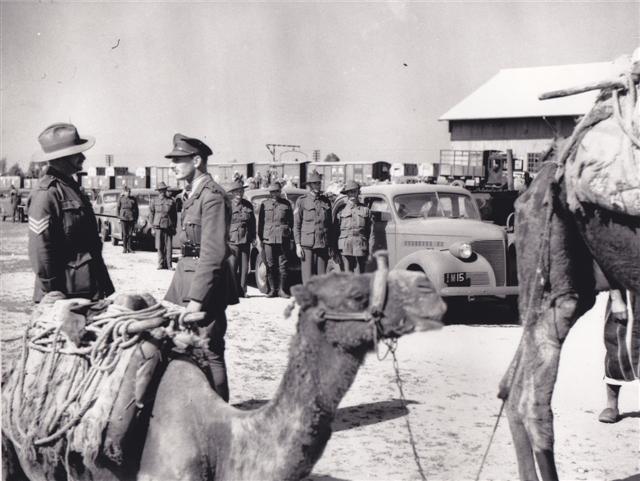

The 6th Division was shipped to the Middle East from January 1940, and authority to raise 7th Division to form an Australian Corps was given at the end of February; it embarked for the Middle East from October. Pressure of events by mid year with the end of the Phoney War saw the AIF target again doubled, supplies and transport units having to be raised for not only the original 6th, but then progressively the 7th, 8th and 9th AIF Divisions and corps troops, for deployment to the Middle East and subsequently Malaya 4. In parallel, the target for the Militia home defence force trebled from the existing 75,000, and all this expansion into a motorised force had to be supported from the springboard of horse transport in the field force, a handful of Permanent unit trucks, and a few supply units. In the first year of the war it appeared that the AIF would again be the separate and distinct force which did the fighting overseas. This turned out to be fact initially, as both theatres were outside Australian territory, and no government had the stomach for a repeat of the risk and divisiveness of the World War 1 conscription for overseas service referendums. But Japan's entry into the war in December 1941 and its successful drive into Australia's environs and territory changed that, bringing the Militia into operations beside the returning AIF units; and coincidentally, a less than creditable and increasingly meaningless but acrimonious division between the two artificially divided components.

The forces in Australia developed quite differently from those in World War 1. While Japan was held in suspicion then, she was a committed ally in the war, her battle cruiser Ibuki even escorting the first AIF convoy overseas. The Universal Training Militia which had then remained in being in Australia was less a home defence force than a training and recruiting ground for the AIF and perhaps a penalty for not volunteering. In consequence the 'as normal' parades and camp training generated little more than had the peace time demands for their support, which was effected by the Militia AASC and contractors, while the AIF training camps, which were largely induction and transit depots to the training depots in the UK and Egypt, got by with AASC units in transit and home-service members. However, after Japan later became an active belligerent in China and Siberia in the 1930s, and was then seen to be threatening a move southward through Indo-China, the home and then forward defence of Australia became a very active priority.

Although some hope was placed in a successful forward defence of Malaya, the Philippines and the Netherlands East Indies, largely predicated on British government assurances of despatch of adequate aircraft and a fleet if the threat became real, there was an increasing recognition that continental defence was a necessary option. The consequent deployment of active forces to Darwin, North Queensland, Western Australia and the Newcastle-Sydney- Kembla and Melbourne covering forces, together with the training camps and schools, plus the depots and workshops for those forces, meant the build up of a comprehensive military supply and transport infrastructure to provide for their support. This required a range of units – from the direct support field distribution and transport companies in the divisions, through the general support transport, supplies, petroleum, bakery and butchery units for those field formations, to base supply and petroleum depots, resources winning units and transport. Once the umbilicus of the British Army providing the bulk of general and base support had been cut, the explosion of such units in the Australian Army caused both a severe strain and a reaction from generals who had never given real thought to the realities of the price of the independence which they cherished as a goal. The list of units in Appendix 5 amply illustrates this cost, however there is very considerable room for challenge of whether all this array was essential: whether units were not simply raised by formula in areas which could be serviced by the civil infrastructure; whether there were not unnecessary links in the chain of supply, again by formula; and whether there was an undercurrent of empire building accentuating the real and essential demands on the support system. In an Army increasingly under political suspicion of maintaining an excessive rank and organisational structure 5, these questions are very valid. As the supporting services naturally have to expand to match the fighting, training and headquarters structures which they are committed to service, any unnatural level of the latter naturally inflates the former.

While there had been a certain amount of necessary re-jigging of units during World War 1 to meet expansions and efficiency regroupings, the story in World War 2 is one of a combination of expansion cluttered by ongoing changes of policy and casual changes of nomenclature caused both by alterations to the command and administrative structure of the Army, and by Corps decisions on what seemed to be a good idea at the time. In 1939 AASC field units were organised on a single commodity basis – supplies, petrol and ammunition, regardless of the previous war's experience of the cost of inflexibility in having dedicated units to meet widely fluctuating demands for each commodity. The sensible decision to follow the UK change in 1941 to the 'brick' system of building up companies of appropriate specialist platoons 6 lasted until 38 companies had been raised (the number in World War 2), after which it all became too hard and transport and composite units became general transport companies numbered in the 100 series. Many supplies units in the lines of communication and base areas were organised not on the brick system but new and odd ones raised and named in a haphazard way, often called by whatever name came first to someone's mind, rather than establishing a systematic and logical system of titles and organisations. Compounding this was the changing overall command system, where AASC lines of communication units changed their title to match changes from Command to Military District to geographic to numerical to formation titles. The over-long list at Appendix 5 consequently shows considerably more unit titles than there were actually different units, but also reflects the uncontrolled growth of an Army that is both having to support itself fully, and being structured and propped up by a commander in chief angling for a field marshal's baton.

The home base and defence of the mainland liabilities saw four distinct functional groups of AASC units formed in Australia:

Training depot units were formed in each Command to handle basic and technical Corps training; advanced and some specialised training was conducted at the AASC School and at MT and other schools in each area.

Base supply depots and petroleum depots of various titles were established in each major area to hold reserves, acquire stock from production, and replenish local and forward depots; base general, car and ambulance transport units serviced base areas.

Lines of communication transport, supplies and petroleum units operated the transport, transit, trans-shipment and forward stockholding system to other commands and operational areas, replenished local complexes and field formations, and won resources locally.

Direct and general support field units, as part of the divisions and of forces formed for protection of vital areas, moved stores and personnel and distributed supplies, petroleum, water and ammunition to units.

Training, base and lines of communication units were generally allotted to the Military District, Command or Lines of Communication Area headquarters in the area they served, except that some with a central role such as the AASC School, Supply Reserve Depots and some general transport companies, were retained under Land Headquarters. Field units were controlled by the force, army, corps, division or sometimes brigade to which they were allotted, and in which they formed an integral part of the operational capability 7.

Overseas forces operated differently at first. The 6th Division on arrival overseas with its integral divisional units, less elements stranded in England when the third contingent was diverted there, slotted into the British structure from which it received significant base, lines of communication and some corps troops support while operating in the Western Desert, Greece and Crete. Similarly 7th Division with its HQ AASC 7 Div, 7 Div Sup Coln, 7 Div Petrol Coy and 7 Div Amn Coy also fitted in to this scheme on arrival at the end of 1940 in Palestine and in subsequent operations in Syria. Formation of 9th Division AASC was less tidy, as part of it was built up in England from the units diverted there – a section from each of 6 Div Sup CoIn and 6 Div Amn Coy, and 7 Div Amn Sub-Park; part of these units was converted to infantry, the remainder formed HQ AASC 9 Div and 9 Div Sup Coln, which arrived in Syria in December 1940 and were completed by 9 Div Petrol Coy and 9 Div Amn Coy on their arrival from Australia in March 1941. To link with the British system, three Supply Personnel Sections were raised in Palestine and operated forward supply depots which were strung out following the advance from Egypt to Cyrenaica 8.

Formation of 1 Aust Corps in late 1941 meant that, as the three divisions were to be independent of British corps in which they had operated, there was a concomitant liability to establish the full range of general support troops, while still relying on the UK system for base support. Components of these units had been progressively raised in Australia and shipped to the Middle East, where they were used in a variety of expedient functions; it remained now to concentrate them into properly controlled units to enable their effective use in their proper role. For the AASC this was also accompanied by the conversion to the brick system, so the divisional units were reorganised as composite transport and supply companies and the corps units into companies and columns. The result was a potentially powerful grouping, the strength of which greatly overshadowed the six MT companies which supported five divisions in the largely static warfare of World War 1. The overseas structure at the end of 1941 is shown in Table 5.

Japanese successes in the Pacific brought this organisation to an abrupt termination. The 8th Division (less a brigade group and its corps troops slice), sent to Malaya from February 1941, was in captivity within a year. Against Churchill's relaxed attitude that Australia could be recaptured later if necessary, the Curtin government recalled 6th and 7th Divisions to form a corps in Java as part of the ABDA Force, but the premature fall of Singapore and then Java pre-empted that force's establishment; the alternative British demand for diversion of 7th Division to Burma was refused, saving its loss there. The 9th Division, with a small slice of corps troops, remained in the Middle East to fight at El Alamein a year later, then returned to the recapture of New Guinea and Borneo 9. The 6th and 7th Divisions, with most of the AASC Corps Troops, returned to Australia and were committed to the defence of Papua and the subsequent offensives in New Guinea and the Islands.

In the interim, Militia forces had been built up for the defence of Australia and Papua New Guinea. AASC composite units were committed with the battalion groups sent to Timor, Ambon and Rabaul, for support of Torres Strait Force and 8th Military District. The original covering forces, which included 1st Cavalry, 1st and 2nd Division AASCs in NSW, 2nd Cavalry, 3rd and 4th Division AASCs in Victoria, and brigade companies in the other states, progressively disappeared, first changing briefly by substitution of motor and armoured division AASCs for the cavalry. Of later duration were the AASCs of the protective forces of 1st Armoured, 2nd and 4th Divisions in Western Australia, and later 12th Division in the Northern Territory and 4th Division in Torres Strait. The shift of Australia's defence centre of gravity as the Japanese forces moved on Papua New Guinea caused major modifications: 6th, 7th and 9th Divisions changed from desert to tropical roles; 5th and 11th were raised and with 3rd Division were later also converted to jungle warfare establishments, with a consequent saving of half of AASC strengths; the armoured and other infantry divisions remained in Australia on normal establishments. The AASC reached its peak of nearly 54,000 in 1943, thereafter declining along with the rest of the Army to the end of the war. It was the second largest corps after Infantry, comprising about 12 percent of army strength. Its structure of 1942 is compared with that of 1944 in Table 6; when it is remembered that many of the formations of the Army had fewer than their normal complement of units, and some units were either undermanned or understrength, the validity of the two field-army order of battle begins to come into perspective.

Within the AASC there were the two streams of AIF and Militia. As the war progressed many of the latter took the option of joining the former, but even then as ex-'chockos' they were known as 'rainbows' for changing colour; many refused the transfer on principle 10. While the virulence of this dispute in the AASC was considerably less than amongst the hardheads in the infantry battalions, there was still an undercurrent in the AASC which had to be controlled, just as there was between those who had various campaign ribbons and those who had not. The fighting in New Guinea and the Islands was done by 3rd, 5th, 6th, 7th, 9th and 11th Divisions; 1st Armoured Division protected Perth until disbanded in 1943 and 4th Division Torres Strait until replaced by 11th Division in October 1944; 12th Division defended Darwin; 1st and 2nd Cavalry became Motor Divisions, then were absorbed into the armoured divisions; 2nd, 3rd Armoured and 1st, 2nd and 10th Divisions became training and administrative organisations, progressively disbanded from February 1943 to May 1945 11. While those AASC units with the fighting divisions bore the brunt of the privations, there was also the other half in the mass of units and men in the bases and lines of communication on which the effort at the front depended. As has been noted before, there were other ways of handling some of those tasks; as well, other doubtful activities and organisations which required AASC units to be raised to support them might have been eliminated by less imperially minded commanders. It was an ongoing source of grievance for those members of AASC units who joined to help fight the war that they were committed to rear areas, often remote, desolate and boring. But for all that, it is also clear that much of their work was indirectly instrumental in the successful prosecution of operations at the front.

While the spoils may go to the victor, the hard work went to the AASC in the occupation of Japan after its surrender on 16 August 1945. The Australian component of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force was formed on Morotai from volunteers. Accompanying 34th Brigade were the specially formed HQ AASC BCOF, 168 GT Coy, 41 Adv Sup Dep of seven supply depot platoons, 47 Fd Bking Pl, 20 Fd Bch Pl, 8 Port Det and part of 6 MAC, plus a DADST and staff on the Brigade Headquarters; this was later augmented by HQ CAASC, 169 GT Coy and 78 BIPOD Pl from Australia. Arriving from February to March 1946 in the devastated Kure area at the end of a bitter winter, with the immediate responsibility of ongoing port clearance and supporting 35,000 Commonwealth troops, proved a somewhat different but equal challenge to those experienced in operations during the war. It was also unique that the RAASC was for the first time the senior partner in a Commonwealth force, rather than providing direct support for its own elements within an RASC structure. This lasted for six years until the major role was taken over by the RASC at the end of 1951, the final elements being withdrawn in 1956 12.

Interim Army, ARA and CMF

The end of World War 2 saw another period of transition as most of the 382,000 remaining members of the Army were demobilised. Once again this demobilisation, together with establishment of the Australian component of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan, took priority over the shape of the ongoing postwar army. AIF disbandment was completed by June 1947, and until the status of the various permanent, ex-AIF and militia members and elements which were carried over could be determined, an Interim Army was established. It comprised the shells of a limited number of units located in the states and territories not already disbanded in the run down process. It also included the component to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan 13.

This interim phase was extended to August 1952 for individuals to allow officers to qualify at special courses known as RMC Wings to meet the Defence Act requirement for permanent commissions. It was very short lived for units – just long enough to finalise a design for a postwar force. This force was a significant departure from that limited by the earlier Defence Act which, based on a long standing popular perception of regular forces being potential instruments of oppression, prohibited regular forces other than artillery and some supporting arms. The increasing technology in warfare meant that not only the gunners required long lead time skills, so a small balanced-force regular army was authorised. The expansion base was still to be the Militia, which was revived as the Citizen Military Forces, a title which had existed formally since the 1903 Defence Act but not in common usage, and now used to put away any hangover of the wartime squabbles. The new volunteer Army, established on this duality of Regular and Citizen Force on 30 November 1947 and 1 July 1948 respectively, differed from the 1921 Army in that it did not try to mirror the World War 2 divisions. Rather it mirrored a cross section of the wartime force, and in so doing was balanced to give proper representation of the logistics services rather than simply setting a target of divisions, with the combat support and combat service support to be raised at some later time. The effect was to provide an RAASC order of battle which provided for a full range of units required to support a modern army - the first tangible recognition in peace of Hutton's 1904 dictum that 'an Army without proper supply and transport support is useless for the purposes of war'.

This order of battle was based on a force the equivalent of three divisions 14. With the Pacific area apparently now secured by the demilitarisation of the old and more recent threat of Japan, the Army's orientation was to the traditional fighting ground for Australian expeditionary forces – the Middle East. As with the overall field force structure, the RAASC component was remarkably like that of the AIF corps in 1941 shown in Table 5, with a leavening of base and lines of communication units again very similar to those of 1941 before Japan entered the war; the manpower target of 70,000 for the CMF was also reminiscent of 1939. A bet was being taken that, given a similar starting point, battleground and preparation time, we could get away with it again, but with an additional concession to regional instability in a Regular Army of 20,000. The Cold War and particularly events in China, Korea and South East Asia had changed these perceptions by the end of the 1960s. The 1951 solution of National Service was no solution in that it tended to repeat the problem of 1912 which had been found out in 1914: the CMF at large and RAASC units in particular were bulging with partially trained, less than willing youths, while the volunteers left en masse. While it may have been a force to go to war with given the year and a half of preparation in World War 2, the western Pacific was a much more volatile location. Simply expanding the order of battle and manning it with partly trained conscripts, in an increasingly technical military environment without the skills or equipment to match, was a numerical, not a military solution.

Forward Defence and Reorganisations

As the bet on the Middle East environment was replaced by the regional one, so also evolved the policy of Forward Defence. There was nothing new in this on the surface, except that Australia's previous commitment to wars had been on the basis of fighting in Britain's wars, regardless of their real relevance to Australia. While the new approach was self serving in the sense of joining with 'great and powerful allies' in regional police actions as a down payment for potential return favours, there was also a clear logic in effecting pre-emptive action on someone else's territory. Whereas participation in the occupation of Japan was part of the fruits of victory, a rapid involvement in Korea in 1950 was the opening action in the forward defence policy – not just fighting someone else's wars, but taking an active part in containing the totalitarian bloc's expansion.

The RAASC's share in the force in Korea was meagre, as theatre logistic support was undertaken by the UK and US. Apart from a small forwarding element at Pusan in the initial stages, and some individual members serving in the Commonwealth infrastructure or seconded to the infantry battalions, the main activity was in the base in Japan supporting the Commonwealth Brigades, then Division. Similarly in the subsequent counter-insurgency operations in Malaya the Australian battalion group was incorporated into 28th Commonwealth Brigade within the British support structure: part of 3 Coy RASC headquarters plus 126 Tpt PI were provided by the RAASC. In Australia the ricketiness of the National Service army, in the light of the observable domino effect after the collapse of French power in Vietnam, led to a review of its real capability. The dissipated resources of the Regular Army were concentrated into 1st Infantry Brigade Group including 1 Coy RAASC in 1957, National Service was terminated two years later, and a depleting CMF was revamped on a narrower but more sustainable basis, predicated on provision of a division and its supporting logistics units to a SEATO contingency plan to defend Thailand 15.

This basis remained as an objective until an ill-starred attempt in 1960 to introduce and justify a copy of a US five-battlegroup division designed originally for a nuclear battlefield; that in turn was followed by a review of the lines of communication units, resulting in wholesale emasculation of the hard learnt lessons of World War 2. The unravelling of this division in 1965 into an air mobile army again left the supplies and transport service without the resources for sustained support of any sustained operations 16. As the commitment to Confrontation in Malaysia from 1963-66 was small enough to avoid testing this, particularly as once again it was within a British Far East Strategic Reserve support structure, the depleted state of the RAASC went unnoticed until involvement in Vietnam began to reawaken some recognition of the fallacy of structuring the army on combat units alone, which had bedevilled the Australian Army from its inception. The real problem was that a small Regular Army tended to follow the one doctrine which in turn was followed by the CMF: when it was open warfare, everyone organised and trained that way, and similarly when the mood swung to variations of tropical, air mobile, counter-insurgency and continental defence concepts. It was not until 1979 that a CGS D.B. Dunstan had the nous to listen to the voices of rationalism and for the first time to structure and train the Army – regular and reserve – on a multi-role basis. Until then, hard won lessons and techniques across a broad range of contingencies and environments were discarded for new fads, and retrieved only partially at enormous cost and effort when needed.

Support of Vietnam

The commitment to Vietnam was preceded by the reintroduction of National Service - this time as either full time duty or with the CMF – making available a ready supply of manpower which, coming from 20 year olds, provided a more mature base that also was a source of junior officers and NCOs. The original RAASC input to the Australian Logistic Support Company which accompanied 1 RAR to Vietnam in 1965 was easily enough accomplished as small transport, supplies and petroleum detachments only were required; again the US Forces provided most logistic support. Expansion of the force to a task force with a logistic support group operating independently had a major effect, even though the US logistics system continued to provide the bulk of supplies and transport infrastructure as had the British system in the continental wars. It was also decided that tours of duty were to be one year, and that repeat tours must have at least a year spacing. This meant that at first one, then two companies had to be turned over on an annual basis which meant that, even after it was decided to replace men progressively rather than unit reliefs, so the equivalent of four regular companies were needed in Australia to back the two in the field. The resultant expansion doubled the Regular component to 4,000 and the CMF by half to 2,700, once again taking the Corps to the over-ten percent of the Army which had obtained in World War 2, demonstrating again the unavoidable reality which was usually forgotten in peacetime resource allocations 17.

As part of the Logistic Support Group for the force, 1 Coy was dispatched in April 1966, replaced by 5 Coy the following year. A separation of functions at the end of 1967 had 5 Coy in the Logistic Support Group and added 26 Coy as part of the Task Force for its immediate support, so cementing two separate base areas. As a consequence of the build up in both Australia and overseas, 9, 18 and 25 Coys were converted to full time duty to act as reinforcement units; similar problems were met and solved with air dispatch, postal and petroleum units, which coincidentally began to restore some balance to the supplies and transport order of battle for the Army as a whole. In the meantime, the Regular and CMF RAASC in Australia, as with the rest of the Army, was organised and trained as if it was all destined to fight in Vietnam, yet this possibility was never contemplated.

Table 7: RAASC Field Force Order of Battle 1951, 1957, 1963, 1970

ANZUK Force

The comfortable arrangement of providing a battalion group to operate within 28th Commonwealth Brigade as Australia's contribution to forward defence of the South East Asian dominoes was shattered by the British government decision to withdraw from east of Suez by 1971. Its effect was that Australia took an unusual initiative to maintain, in conjunction with New Zealand, a military, naval and air force on permanent station in Malaysia-Singapore. Without the British base infrastructure, a modest logistics structure was required in the base area, and 112 ST Coy arrived in Singapore in November 1970 to pick up the pieces as the British wind-down concluded and the ANZ brigade withdrew from Malacca to the Island. However at this stage a change of government in the United Kingdom brought a limited reversal of policy to maintain a small physical presence in the area; with this the British forces sought to re-assume the natural order of their primacy, with the ANZ element as junior partners. This was not accepted, and in the hastily arranged ANZUK Force, Australia remained logistics manager with British and New Zealand participation. Logistic support was provided by ANZUK Support Group, which included a CRAASC and staff, ANZUK Base Transport Unit, ANZUK Supply Depot and ANZUK Postal and Courier Unit. These units were essentially static base ones, with mixed manning from the three countries and, as RASC had been disbanded six years earlier, the RAASC and RNZASC members were joined by RCT in the Transport Unit, RAOC in the Supply Depot, and as their postal service had not changed, by RE in the Postal Unit. In addition to the servicemen, a high proportion of the manpower of the units was provided by local civilians. 28th Commonwealth Brigade was not to be on an immediate war footing, so as an economy measure two platoons of field transport – 90 Tpt Pl RAASC and one RCT troop, together with a headquarters and workshop component – were provided in the Base Transport Unit for deployment in support of periodic exercises; in addition, Supply Depot and Postal Unit also supported visiting ships and Tengah air base 18. But the greatest workload came from supporting the domestic infrastructure, with a fleet of 100 buses and other passenger vehicles taking children to and from school, and the servicemen to and from work across the Island.

This was an indian summer of the raj, and lasted as long. The Force never had an air of permanence, living on minimum resources in the climate of withdrawal from foreign entanglements engendered by the aftermath of the Vietnam disengagement. A change of government in Australia at the end of 1972, just over a year after ANZUK Force was formed, saw a decision to withdraw from the forward defence posture. Military tripwires in South East Asia were to be a thing of the past: Australia's defence forces were required to be in Australia.

Fortress Australia

The requirement for a defence force in Australia was, however, less than enthusiastically acknowledged in some sections of government and a politicised bureaucracy. Encouraged by fellow-travelling media and patio intellectuals propelled by Orwellian peace propaganda, these elements moved to reduce the Armed Forces' strength and morale, and redefine their mission as one of aid to the civil community. Fortunately some wiser political heads and the resilience of the military largely withstood this, and the Army was also able to begin recovery from the total obsession with counter-insurgency. It was the beginning of a hard road, as a military generation had known nothing else: company commanders and senior instructors had never been trained in open warfare under an air threat and so could not train platoon commanders who in turn could not train their men. In fact, some continuity came from the CMF and a remnant of more senior Regular officers who had preserved some memory or maintained professional studies sufficiently to begin restructuring, but the imminent split of RAASC to Transport and Ordnance was an additional burden which left them to carry their knowledge forward in that less sympathetic and comprehending environment. As a result the process became longer drawn out and less complete in concept and execution than need have been. But, with the political assessment of no foreseeable threat for ten to fifteen years, what was the problem?

Footnotes

1. Table 3; Long G. To Benghazi p40.

4. McKenzie-Smith G.R. 'The Numerology of the Second AIF (Infantry) 1939 to 1945' Sabretache April-June 1989, p3; Long, p82, 86-7, 123.

5. For a partial general discussion of this see Long G. The Final Campaigns Appendix 2.

6. See Chapter 17 and Table 13, Table 14 and Table15.

7. See Table 6; Army Order of Battle December 1941, 1942-43, 1944; RACT Museum DST Files 1-11 AHQ Operation Order No 50 of 9 April 1942.

8. Fairclough, p114-6; AWM 52 10/2/21, 10/2/23, 10/2/25 War Diaries passim.

9. Wigmore L. The Japanese Thrust p442-6, 452.

10. Long G. The Final Campaigns p77, 79; Wigmore, p59.

11. Long, p34, 81, 602-3; Dexter D. The New Guinea Offensives, p13, 16, 227, 280.

12. Fairclough, p261-4; AWM 52 10/2/37.

13. Long Final Campaigns p581.

14. AWM 51146; AA MP729 837/432/106; AWM 54 703/5/1.

15. AHQ 01358 of 19 June 1958; Army ORBAT 1960.

18. '112 S and T Coy RAASC – Singapore' RAASC Digest 1971, p95-6.