Chapter 1

Origins

The origins of military supply and transport stretch back to the emergence of large forces which operated away from their own centres in such numbers that foraging could not supply all or most of their needs. However, whilst the expeditionary forces of Sumer, Babylon, Egypt, Hatti and Assyria obviously needed and were accompanied by a well organised logistic support system, apart from some brief allusions, the nature of the records which those empires have left to us sheds little light on how this was effected.

Herodotos of Halicarnassos 484-425 BCE

Herodotos was an eastern Greek – a traveller and recorder who wrote his Historia (Researches) in about 440 BCE.

Herodotos was an eastern Greek – a traveller and recorder who wrote his Historia (Researches) in about 440 BCE.

It included a detailed account of the Persian expeditions against Greece in 490 and 480 BCE by Darius and Xerxes. Although not an eyewitness, his work is more reliable than other more fragmentary sources, provided adjustments are made for numerical exaggerations.

King Darius I

Darius the Great ruled the Persian Empire 522-485 BCE. He attempted to subdue Scythia (present Ukraine) and failed against a war of attrition mounted against him.

Darius the Great ruled the Persian Empire 522-485 BCE. He attempted to subdue Scythia (present Ukraine) and failed against a war of attrition mounted against him.

His later punitive expedition against Athens and Eretria was also turned back at Marathon 490 BCE. He then planned to subject all of mainland Greek cities to prevent their interference in the Greek cities in his Asia Minor province, but died before he could attempt this.

King Xerxes I 519-465 BCE

Xerxes the Great ruled the Persian Empire 485-465 BCE.

Xerxes the Great ruled the Persian Empire 485-465 BCE.

He inherited his father Darius’ project of subjugation of mainland Greece to establish an ethnic frontier in the west, but lost his fleet, and its dominant amphibious and essential logistic capacity, at the naval battle of Salamis 480 BCE.

With his resupply eliminated, he had to take half his army home and so lost the land battle at Plataia the following year.

Our first coherent descriptions of military logistics appear in Herodotos’ history of the Persian and Greek wars of the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. Here it becomes immediately apparent that commanders not only understood the necessity for effective logistic support in the field, but also knew the effectiveness of denial of this to their opponents. Herodotos gives descriptions of how the Scythians very nearly annihilated Darius I’s army north of the Black Sea by a war of movement and denial; of the immense, carefully planned arrangements made for Xerxes’ invasion of Greece in 480; of the withdrawal of a major part of that army prior to winter after defeat of the Persian fleet left the sea supply line vulnerable; and at the deciding land battle of Plataia, of the Persian cavalry cutting off the Greek mule trains, forcing them to divert half their army to defending their lines of communication 1.

Polybios

Polybius, a Greek aristocrat and general of the Achaean League, was held as a hostage in Rome where he tutored the Scipio children and busied himself writing both The Histories covering the Second and Third Punic Wars 220-146 BCE and a treatise on tactics.

Yet while the necessity of providing supply trains was well recognised, the administrative principle of economy of effort was also clearly understood: wherever possible, troops were paid a subsistence allowance and required to purchase their rations at local markets. This system is well recorded early in the Greek wars 2, and its use continues through to this day wherever it can be employed; however the growing demands for supply and movement of field armies have increasingly dictated the provision of organised trains, whether arranged by contractor, commissariat or military organisation. Polybios, in describing the Roman military system of the mid-second century BCE, makes it clear that, in the field, the administrative staff officer of the force was made responsible for issuing rations and equipment, deducting the cost from soldiers’ pay; he also describes the positioning of the baggage train on the march and measures taken to protect it 3. By this stage patterns of logistic support had been set which were to last two thousand years.

Emperor Charles I Augustus the Great 742-814

Charlemagne was king of the Franks in Spain 768-814. He became embroiled in wars on several fronts, supporting the papacy and removing the Lombards from power in Italy; fighting the Saracens invading France from Spain; and subjecting the Saxons in Germany and forcibly converting them to Christianity.

Charlemagne was king of the Franks in Spain 768-814. He became embroiled in wars on several fronts, supporting the papacy and removing the Lombards from power in Italy; fighting the Saracens invading France from Spain; and subjecting the Saxons in Germany and forcibly converting them to Christianity.

He intended to crown himself Holy Roman Emperor in 800 CE, but the Pope seized the crown and put it on Charles' head, proclaiming him Imperator Augustus, as a gift from the papacy – Charles had to be restrained form cutting him down. This established the precedent of the power of the papacy to appoint and remove kings, and the claim of divine right of kings.

Charles' campaigns were underpinned by ensuring that proper provision was made to sustain his forces in the field.

King Gustav II Adolph

Gustavus Adolphus the Great built and ruled over the Swedish Empire 1611-1632.

Gustavus Adolphus the Great built and ruled over the Swedish Empire 1611-1632.

His prosecution of the Thirty Years War laid the foundations of the Swedish Empire for a century, and earned him the title by some of ‘father of modern warfare’.

Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein Duke of Friedland 1583-1634

Wallenstein was a Bohemian politician and soldier who was appointed supreme commander for Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II during the 30 Years War which devastated central Europe.

Wallenstein was a Bohemian politician and soldier who was appointed supreme commander for Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II during the 30 Years War which devastated central Europe.

He was successful in turning around the victorious progress of the protestant armies, but aroused the suspicion of Ferdinand that he might defect to the other side, and was assassinated.

Attention to this inescapable facet of warfare is further exemplified in the Byzantine army from the eighth century which included a baggage train and supply column, established at the rate of a rations cart, an equipment cart and a pack horse to each 16 men, enabling sustainability of operations which kept at bay much stronger foraging armies for six centuries. A century later Charlemagne required his levies to come equipped with three months of food and tools, with covered carts waterproofed for river crossings. On the other hand, Iater Germanic Holy Roman Emperors in the tenth to twelfth centuries faced successive failures in their wars against the Poles and Hungarians because of administrative failure; the same reverses were mirrored in the French and English dynastic wars in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, precluding the sustainment of any significant forces in the field. Even Gustavus Adolphus, who tried to produce a new look army, lost a contest with Austria's Wallenstein in starving each other out in 1632, but the latter's forces were too debilitated to follow up their success.

Marquis Michel le Tellier

Minister for King Louis XIV as Secretary of State for War 1643-66 and Chancellor of France 1677-85, he reformed the army into a large professional force which enabled French dominance in Europe.

Francois-Michel le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois

Secretary of State for War 1666-1691 during the reign of king Louis XIV, he continued the army reforms of his father, which enabled French dominance in Europe.

Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu 1585–1642

French clergyman, aristocrat and statesman, he became Louis XIII's chief minister 1624-42

French clergyman, aristocrat and statesman, he became Louis XIII's chief minister 1624-42

He sought to consolidate the king's power at the expense of that of the aristocracy, and opposed the Austro-Spanish Habsburg empire, leading to the Thirty Years War which convulsed Europe.

Sustained warfare had become restricted to proximity to supply magazines, until a renaissance of mobile warfare began with le Tellier's restructuring of the French army – first in Italy in 1640, and subsequently throughout the whole force. A corps of superintendents oversaw the efforts of contracted sutlers supplying at set scales of issue, and an equipage des vivres furnished a mobile magazine. His son Louvois took this a step further in rationing soldiers free of charge and establishing general supply depots in addition to fortification depots, so that external operations could be supported reliably, but neither developed a standing transportation corps, relying on requisitioned and hired wagons and barges. Nevertheless, from hereon effective logistics began to reappear and permit the support of mobile forces of some size, so facilitating the resurgence of major organised warfare by professional armies rather than small skirmishes or overrunning hordes. Richelieu's aphorism 'history knows more armies ruined by want and disorder than by the efforts of their enemies' is well grounded. It is as well to follow not the footsteps of Clausewitz's 'mere bravos' but rather the paths of successful generals; and in those paths will be found successful logistics, a factor too often overlooked by those today who pay lip service to support of forces in the field. In adding Administration to the Principles of War, Montgomery was doing no more than formalising a truth recognised by winners and ignored by losers for three thousand years 4.

Major General Carl von Clausewitz

After serving in the Prussian and Russian armies during the Napoleonic Wars, he was appointed Major-General and director of the Kriegsakademie (Prussian Military Academy) 1818-1830.

After serving in the Prussian and Russian armies during the Napoleonic Wars, he was appointed Major-General and director of the Kriegsakademie (Prussian Military Academy) 1818-1830.

His military philosophies are encapsulated in his book On War.

Field Marshal B.L. Montgomery Viscount Montgomery of Alamein

Montgomery commanded Commonwealth forces in North Africa, Italy and North West Europe 1942-45.

Montgomery commanded Commonwealth forces in North Africa, Italy and North West Europe 1942-45.

His experience in support of these forces convinced him that Administration should become the 10th of the British Army Principles of War.

The early emergence of a necessity for military support systems was accompanied by problems in sourcing the supplies and the transport. Pre-industrial economies could not support the large scale continuous maintenance of wagons, animals and supplies held ready solely for potential military activities, so the economy principle once again dictated alternatives which once again survived into recent times – local procurement by contract, purchase, hiring, requisitioning and impressment, with foraging or looting as an augmentation only 5. Such expedient means provided an acceptable basis of support for pre-industrial warfare, but growing technology, and the superiority it brought, progressively imposed the need for more specific and certain supply systems. From this need evolved, often after painful lessons, standing logistics organisations and materiel stocks. And this evolution led to the formation of supply and transport corps or their equivalents in all modern armies.

The development of Australia's armed forces substantially followed that of its British parent. So while the Australian Army Service Corps had its own quite separate origins which are described subsequently, the British experience is relevant both as providing the background of the evolution to a standing organised supply and transport structure, and in examining the impetus for a similar organisation under quite different circumstances in Australia.

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington

Wellesley, later victor at Waterloo in 1815, commanded the Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese forces against the Napoleonic French occupiers of the Iberian Peninsula in the Peninsular War 1808-1814.

Wellesley, later victor at Waterloo in 1815, commanded the Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese forces against the Napoleonic French occupiers of the Iberian Peninsula in the Peninsular War 1808-1814.

One of his overarching concerns was the logistics of supporting the armies during the campaign, with the United States of America joining the French in attempting to disrupt his sea supply lanes.

Captain-General John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough

Marlborough rose to prominence first in the Nine Years War in Ireland and the Netherlands 1688-97, then in the War of Spanish Succession 1701-14.

His successes were built on effective organisation and support of his armies.

Transition in British armies from haphazard impressment and foraging to organised military supply and transport systems was a slow and halting process 6. Marlborough's insistence that his troops be messed regularly on repayment, and organisation of an effective baggage train, merely meant that he had, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, caught up with the Roman system of nearly two thousand years earlier. A hundred years later Wellington in the Peninsula War found it necessary to follow personally the activity of his Commissariat, but this eventually well honed system of procurement, depots and transport evaporated after the campaign: a Commissariat was operated by Treasury employees, albeit many ex-soldiers, so the end of a war meant the end of the structure built up for it. And embryonic transport organisations under military control waxed and waned: the Royal Waggon Train, successor to the earlier experiments of The Corps of Waggoners (1794-6) and The Royal Waggon Corps (1799-1802), performed excellent service in the Peninsula from 1802. However Wellington, proponent though he was of retaining a peacetime core organisation, sacrificed it in the 1833 Army reductions.

It required the debacle of a breakdown of the administration system in the Crimea in 1854, and the consequent fall of the government, to force recognition that logistic support of field armies is as much a part of the military activities as is the fighting, not just a job for accountants and paymasters with their eye on their Treasury masters. The outcome was the transfer of the Commissariat Department from Treasury to War Office, raising of a Hospital Conveyance Corps for medical evacuation, and the following year the Land Transport Corps, which absorbed the Hospital Conveyance Corps. It was established as part of the regular army and, although the Commissariat under the War Office remained a civilian body, the Corps was a combatant military organisation.

By the end of the Crimean War, the value of having a nucleus peacetime organisation was once more recognised, this time with more success. The ten years of soul searching in the defence establishment after the war enabled the transport organisation to survive the usual disbandment moves, retitled as the Military Train (1856). The Commissariat also gained financial independence from the Treasury and was reformed as a Commissariat, Medical and Chaplains Department; in 1859 a partially military Commissariat Staff Corps was formed which drew on line regiments for its non-commissioned members who were held supernumerary in those units. Ten years later, after protracted War Office reviews which recommended single control of supply and transport, a Control Department was formed, incorporating Supply and Transport Sub-Departments and an Army Service Corps (replacing the Military Train), the officers of which were still departmental civilians. In 1875 the Control Department became the Commissariat and Transport Department; in 1880 a Commissariat and Transport Staff was formed, through which military officers replaced the civilian officers; and in 1881 the ASC was redesignated Commissariat and Transport Corps - still a corps of other ranks, with their officers coming from the Commissariat and Transport Staff. At the same time, ASC ordnance companies were transferred to the Ordnance Store Corps.

This set the scene for the final move in 1888. Quartermaster-General Sir Redvers Buller instituted the Army Service Corps to replace the anachronistic duo of the Commissariat and Transport Staff and Corps, though interestingly this was nearly two years after the Colony of Victoria formed its embryonic Corps. The ASC was fully combatant, with officers and men at last in the same organisation, having the task of the acquisition and delivery of combat consumable stores. The evolution was nearly complete, wanting only its setting in place and its testing in war. However, how that happened is the story of the British ASC. That of the Australian counterparts has a different beginning.

Australian Colonial Beginnings

Lieutenant James Mario Matra 1746-1806

Matra was a New Yorker who sailed under Cook on his 1770 voyage to Australia, and subsequently fought in the American War of Independence on the Loyalist side.

He proposed to the British government in 1783 that a commercial colony be established at Botany Bay, to be settled by the loyalists who had fled to Canada after the end of the War. He further proposed it as a less deadly place than Africa for settlement of convicts, now that transportation to North America was precluded.

Admiral Sir Arthur Phillip 1738-1814

Captain Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales on the basis of his experience controlling a convict-manned military and trading colony in Brazil during the Spanish-Portuguese war.

Captain Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales on the basis of his experience controlling a convict-manned military and trading colony in Brazil during the Spanish-Portuguese war.

He established the military colony using convict labour at Port Jackson in 1788, returning home ill in 1792, leaving Major Francis Grose as acting Governor.

He was subsequently promoted to Admiral.

A military supply and transport system existed in Australia from the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. As a strategic military penal station, in a territory devoid of agriculture or infrastructure, the Botany Bay settlement was launched to operate initially on government stores and transport services: James Matra's proposals, Sir George Young's plan and the Instructions for Governor-in-Chief and Captain-General Arthur Phillip called for increasing self-sufficiency, but this was to be later 7. In fact it was very much later. The colony and its inhabitants, one way or another, remained 'on the Stores' for decades; the Commissariat was not just a supply depot for the military and convicts, but remained a major factor in the life and economy of New South Wales until the run down of transportation in the 1840s in the eastern colonies and the 1860s in the west.

Admiral Sir George Young 1732-1810

Young was captain of the Royal Yacht William and Mary with wider interests. He had proposed colonisation of Madagascar, which was rejected.

Young was captain of the Royal Yacht William and Mary with wider interests. He had proposed colonisation of Madagascar, which was rejected.

When he became aware of Matra’s proposal for Botany Bay, he took it up and developed it into a plan which he presented to the government in 1785, based on the American Loyalists, Chinese, South Sea Islanders and convicts; the plan detailed the ships, stores and military forces necessary to start the colony.

Admiral John Hunter 1737-1821

Hunter was commissioned in 1780, and came with the First Fleet as second captain on Sirius. After losing the ship at Norfolk island, he returned to England. Although the ailing Phillip recommended Philip King as his successor, Hunter was chosen and arrived back after an inter-regnum of governance by NSW Corps officers Grose and Patterson; the Corps’ dominance of farming and commercial interests was established by the time of his arrival in 1795.

Hunter was commissioned in 1780, and came with the First Fleet as second captain on Sirius. After losing the ship at Norfolk island, he returned to England. Although the ailing Phillip recommended Philip King as his successor, Hunter was chosen and arrived back after an inter-regnum of governance by NSW Corps officers Grose and Patterson; the Corps’ dominance of farming and commercial interests was established by the time of his arrival in 1795.

He failed to establish his authority, the odds being stacked against him by his miniscule administrative staff and few sympathisers in the free population, and the diverse and indecisive directions from London. After Macarthur saw his initial manipulative success fail, he turned against Hunter and worked for his recall.

Hunter attempted to impose restraint on profiteering by the military which was crippling commerce, and attempted to direct the Colony to self-sufficiency based on private production. The NSW Corps was able to convince the home government of his shortcomings and he was replaced by Philip King in 1800.

Allen entered the imperial Commissariat in 1807, replacing Commissary Palmer after the restructuring of the NSW Commissariat in 1813, initially gaining the patronage of Governor Macquarie and becoming a large landowner.

Allen entered the imperial Commissariat in 1807, replacing Commissary Palmer after the restructuring of the NSW Commissariat in 1813, initially gaining the patronage of Governor Macquarie and becoming a large landowner.He began manipulating trading and treasury bills, and Macquarie revised his opinion of him to 'considerable private and Clandestine commercial Speculations', and poor control of his staff with 'a most prejudicial effect', two of whom were subsequently found guilty of fraud.

He was replaced by Drennan in 1819, and was described by one officer as 'a compound of perfidy, hypocrisy and I may even add dishonesty'.

Major General Lachlan Macquarie CB 1762-1821

Macquarie joined the British army at 14, was commissioned in 1777 during the American Revolutionary War and returned in 1784. He subsequently served with the army in India and by 1805 as a lieutenant colonel commanded the 73rd Regiment of Foot.

Macquarie joined the British army at 14, was commissioned in 1777 during the American Revolutionary War and returned in 1784. He subsequently served with the army in India and by 1805 as a lieutenant colonel commanded the 73rd Regiment of Foot.

In 1810 he was appointed Governor of New South Wales, taking his regimemt to replace the NSW Corps, which he reformed into the 102nd Regiment and despatched to fight the latest war in America. He regained control in the aftermath of the Johnston-Macarthur coup against Governor Captain William Bligh and set about improving the colony in buildings, social equality and prosperity, suppressing the excesses and corruption left as a legacy of the NSW Corps but saddled with the criticisms of Commissioner Bigge.

Major George Johnston 1764-1823

Originally a lieutenant in the Marine detachment which accompanied the First Fleet in 1788, he was sent to Norfolk Island in 1790, then acted as adjutant to Governor Arthur Phillip. He transferred to the New South Wales Corps in the rank of captain in 1792 when it began to arrive to replace the Marines.

Originally a lieutenant in the Marine detachment which accompanied the First Fleet in 1788, he was sent to Norfolk Island in 1790, then acted as adjutant to Governor Arthur Phillip. He transferred to the New South Wales Corps in the rank of captain in 1792 when it began to arrive to replace the Marines.

He received extensive land grants in the Sydney and Georges River area, was appointed adc to Governor John Hunter and promoted to brevet major in 1800, then arrested by CO of the NSW Corps and Lieutenant Governor Lt Col William Paterson for trading in spirits and disobedience of orders. Sent home for court martial, the charges were dropped on evidential difficulties, and he returned in 1802 to take command of the NSW Corps during Paterson's illness, where he entered into regular disputes with Governor King.

He was instrumental in the quick and decisive suppression of the Castle Hill uprising instigated by Irish convicts, and when Paterson was sent as Lieutenant Governor in Van Diemen's Land, became commander of the NSW Corps, entering into acrimonious dispute with Governor Bligh. Egged on by John Macarthur who was facing court martial, he initiated a coup to overthrow Bligh and assumed the title of Lieutenant Governor. Sent home for court martial again, in 1811 he was found guilty of mutiny and given the extremely mild penalty of being cashiered.

Returning in 1813, after Macquarie was instructed to treat him like any other settler, he lived out his life on his property at Annandale.

In support of the prosperity objective on which his social improvement programme rested, he minted local currency and supported establishment of the Bank of New South Wales. His anti-corruption activities resulted in the removal of Commissaries Allen and Drennan.

His appointment ended the run of naval governors who inevitably found themselves in conflict with and white-anted by the army establishment. He was promoted progressively to colonel, brigadier and major general in the first three years of his governorship, which terminated in 1821, his successor being Sir Thomas Brisbane.

Judge John Thomas Bigge 1780-1843

Bigge conducted a royal commission in New South Wales to examine the effectiveness of transportation as a deterrent to felons.

Bigge conducted a royal commission in New South Wales to examine the effectiveness of transportation as a deterrent to felons.

His three reports in 1822 and 1823 contained measures for the administration of NSW and Van Diemen’s Land, remedies for civil inefficiencies and disposal of crown land, and measures to limit dependence on the Commissariat.

The reports were, by implication, a criticism of Macquarie’s administration – the latter responding that they 'gave no knowledge of the present state of the colony'. It fell to Governor Brisbane to implement the outstanding items of merit, and avoid the irrelevant and prejudicial.

By late 1800, of 4,936 free and bonded persons in the Colony, 2,954 were victualled by the Commissariat. While governors were very conscious of reducing the claim on the Commissariat by military and convict beneficiaries, the ruinous effects of profiteering by the New South Wales Corps and other traders forced Governor Hunter to ask the Treasury to authorise the Commissariat to supply the settlers with 'everything at a fair rate'. This took the form initially of exchanging stores for produce to break the monopolies, then from 1802 surplus perishables were sold to free settlers, lasting until 1815 8. Drawing of rations from the store by officials and their families was both a financial boon and status symbol; military families were successively 'kept on the stores' or 'struck off the store' and back on again as governors' sympathies changed. The most heartfelt plea came from the Commissariat custodian himself – Deputy Commissary General Allen who objected to his family being struck off along with those of all civil officers by Macquarie in 1814, attempting unsuccessfully to argue that the Commissariat was a military unit and that he was a military officer; he was over 60 years early in being technically correct in this claim, although as part of a quasi-military organisation commissary officers were shown in the Army List. Shortly after Commissioner Bigge's report was less than enthusiastic on these liabilities on the Treasury and the dependant and parasitic mentality they sustained; in response, Governor Brisbane acknowledged of the convict clientele in Sydney that 'their two great inducements for lingering here were the little work that was obtained from them and the great ration that they received' 9, and took steps to remove their talents to production rather than consumption of food.

Major General Sir Thomas Brisbane GCH, GCB 1773-1860

Brisbane had a distinguished career in the Napoleonic Wars and was recommended by Wellington as governor of New South Wales, which he filled 1821-25, carrying out many of the recommendations of the Bigge Report into the Colony’s administration.

Brisbane had a distinguished career in the Napoleonic Wars and was recommended by Wellington as governor of New South Wales, which he filled 1821-25, carrying out many of the recommendations of the Bigge Report into the Colony’s administration.

To overcome official corruption he established a system of public tenders for government services and boards of survey on disposal of stores.

He also established the penal station at Moreton Bay. The present capital of Queensland is named after him, however the city owes no debt to his advice to the Commandant not to worry about layout or wide roads as it would never be more than a penal colony.

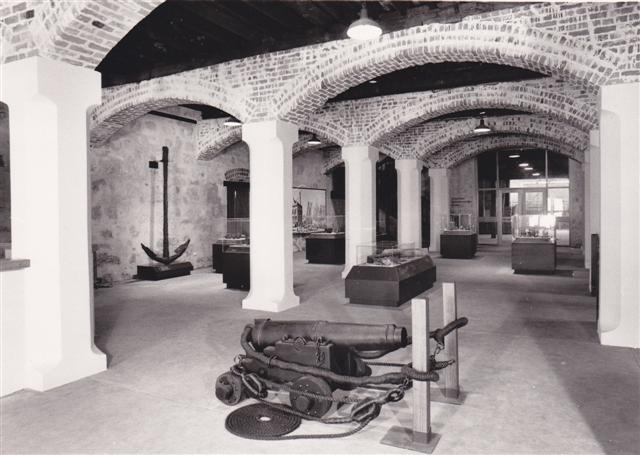

Commissariat depots were established as the need arose. The original Commissariat store was established at Sydney Cove in 1788 with Norfolk Island opened immediately after to support the penal station later abandoned and burnt in 1814; a store was opened at Parramatta in 1792 when settlement, barracks, and convict establishments required this. Windsor was opened in 1794 primarily as a grain repository when agriculture developed on the Hawkesbury; by 1800 Toongab-be and Liverpool were in operation. As settlement expanded, convict work stations with military guards were established, military protective outposts opened, and Commissariat stores accompanied them. Hobart Town Commissariat was opened in 1803 with the penal station, and a second at Port Dalrymple (near Launceston) when it was set up later that year to counter French interest. The Newcastle store from 1804 supported the penal station re-established for Irish convicts after the Castle Hill uprising, Bathurst in 1817 after expansion over the Blue Mountains, and in Melbourne for the guard detachment for settlement of the Southern Districts from 1835, using a shed and a cart hired from John Batman.

Separate Commissariat administrations reporting direct to the Board of Treasury in London were set up in each separate colony: Hobart in Van Diemen's Land two years after separation in 1827; Fremantle in 1831 after establishment of the Swan River Colony two years earlier; and Adelaide in South Australia similarly in 1842; however Victoria remained as part of the NSW organisation until 1854 when the Commissariat headquarters moved to Melbourne at the same time as that of the Military Forces. For local coordination the Deputy Commissary General, first in Sydney then Melbourne, arranged inter-colonial troop, specie and stores movement where this was required by the Australian Command, and the support of operations in the New Zealand wars.

Commissariat detachments operated at Fort Dundas on Melville Island 1824-28 and Fort Wellington on Raffles Bay 1828-29 to service the abortive attempt at a South East Asian trading centre, the latter being re-established as Victoria on Port Essington 1838-49 in a vain re-attempt. Also provided with commissariats were the penal stations at Port Macquarie 1820-29 for a penal timber industry; Moreton Bay for the penal station 1824-42, then the garrison of the free settlement until 1850; Norfolk Island reopened 1825 to hold recidivists from NSW; Macquarie Harbour for Tasmania's incorrigible criminals to win coal and timber 1821-33, together with Maria Island 1825-32 and 1842-50 for lesser criminals; and King George's Sound as a strategic harbour in 1828, coming under Swan River Colony in 1831, then from 1850 as a convict establishment. Norfolk Island was expanded 1844-56 under the Van Diemen's Land Commissary in concert with Port Arthur 1830-71 as those stations became the repositories of all convicts in Australia under the 1842 rehabilitation scheme. In addition to the network of permanent and semi-permanent stores, others were established in many other locations on a temporary basis to meet particular deployments, such as the abortive penal stations at Hunter's River 1801, Sullivan's Bay (Sorrento) 1803, Westernport 1826-28 and Port Curtis 1846-47, with other outstations at Champion Bay, Bunbury, York, Campbell Town, Spring Bay, Portland Bay, Berrima and Blackheath to name but a few. Indeed wherever there was a military detachment or a convict work gang and its guards there was a temporary or semi-permanent Commissariat store; non commissioned officers of military detachments often were co-opted as storekeepers at outstations, drawing additional pay and perquisites for the responsibility 10.

As the Commissariat was initially part of the military establishment which formed the Botany Bay settlement, the Commissary was responsible to the Governor who in turn was responsible to Treasury for its accounts. This changed in 1813 when it reverted to a branch of the home Commissariat through which it then reported. The function of the Commissariat was, in the field 11:

the custody of the Military Chest [descendant of the ages-old war chest] and to provide and pay for everything necessary for the subsistence of the Army; on stations abroad, negotiation of bills for their supply, and receipt of all surplus public monies; making advances to regimental paymasters and heads of the Ordnance and Naval Departments; the payment of military pensions; and contracting and paying for provisions required for the supply of troops, and for land and water transport; in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land additionally to supply provisions, clothing and stores for convicts. Their function blended with the Army, Ordnance, Navy and other branches of the public service. They are under the orders of and responsible for the execution of their duties to the General or Officers commanding at the various stations, and receive their instructions from the Board of Treasury, with whom they correspond through the Secretary on all points of the service on which they are engaged.

When the other functions in the Colony of purchase, sale, barter, exchange and lending were added, it was as near to being a bank as was possible without being one 12. Concomitant with such widespread transactions were equally widespread accusations of corruption, as much as governors and Treasury tried to give instructions to avoid this. As part of the overthrow of Bligh’s administration, Commissary John Palmer, who had been instrumental in Macarthur’s arraignment for corruption which sparked the mutiny, was himself arrested on charges of corruption, while he counter-charged misuse of stores by the rebels 13. A succession of replacements suffered the same fate until Macquarie restored control, and dispatched Palmer to England where he vindicated himself. In 1813, after a world-wide restructuring of the Commissariat service, the position in New South Wales was graded as Deputy Commissary General coincident with the arrival of Allen, and the dispute over his military status was only one facet of a running feud with the Governor on conduct of business, resulting in Allen’s recall in 1819. His replacement Drennan, after sniffing out corruption in the Port Dalrymple store, was himself on his way home three years later, under arrest to explain a missing £6,000, a multi-millionaire figure for that time which would ensconce him as the predecessor of the 1980s entrepreneurs. This salutary move inhibited detected crime, but a more effective long term control was the establishment in 1824 of an Accounts Branch under Commissary of Account William Lithgow, who was specifically charged to take care that the officer in charge of the Commissariat operated in strict conformity with his Treasury instructions 14. The following year Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane issued a detailed manual for the Commissariat’s operation.

A year later Governor Darling reorganised the structure to include a Commissary of Stores controlling both the military and colonial stores which had been allowed to operate separately, and confirmed the system of public auctions and tenders for sale, tenders for supply of stores, and boards of survey for classification of stores. This restructuring flowed on by 1828 to a Stores Branch, which was responsible for provisions, forage, fuel, candles and oil for light, and included a now separately identified Transport Establishment responsible for land and water transport for the military and convict establishment. Also still included were buildings, building materials, furniture and associated labour, until the establishment of an Ordnance Storekeeper’s Department under supervision of a Royal Engineer officer in both New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land in 1836, which absorbed those responsibilities and staff, leaving the Stores Branch in New South Wales a triply diminishing organisation as the convict flow and additional troops were diverted to Van Diemen’s Land after 1840, and the first Maori War drained over half of the troops by 1847. After this flurry of activity, and that caused by incoming Major General commanding Australia Command Wynyard’s less than inspired decision in 1848 to completely relocate the regiments throughout the country, the Transport Establishment was also reduced 15.

The imperial Treasury controlled the Commissariat directly through its agent, the Governor, until 1813, then indirectly through him until the transfer of the Commissariat to the War Office after the Crimean debacle in 1854. With increasing authority being passed to the colony's Legislative Council after its establishment in 1823, the Home Government attempted to add financial responsibility for local costs. Governor Darling divided expenditure into three heads in 1827:

Colonial for everything other than military and convict expenditure

Military for Army and Hospital costs

Maintenance of Convicts

The first was to be charged to Colonial revenues, the others to the Treasury and paid from the Military Chest. An attempt to charge for the upkeep of the veteran companies then being sent out from England as convict guards was withdrawn quickly as local revenues could not support it at that stage, but increasing prosperity reversed that once again 16. From 1836 expenses for prisons and police, including their supply and transport, were charged to the NSW Colonial Treasury. The non-official members of the Legislative Council were quick to recognise that the Colony's taxes were to pay for Britain's penal outcasts and fought a running battle with Governor and Home Government over sixteen years until the cessation of transportation ended the dispute. In addition from 1850 the colonies paid for the upkeep of British garrison troops specifically requested by them, and from 1863 all troops until their final departure in 1870, at the annual rate of £40 for each infantryman and £70 for artillerymen or extra infantry. Consequently the Commissariat, although an imperial function for the support of the British military and convict establishments, had a substantial part of its costs defrayed by funds mulcted from colonial revenues 17.

Rundown of the imperial garrisons and convict establishments brought commensurate reduction in the Commissariat. The Accounts Branch was disbanded in 1847 and the Ordnance Branch almost disappeared after all buildings passed to the Colonial Governments in 1850. The Stores Branch was reduced to the upkeep of the small garrisons in each colony, the running down of Port Arthur prison, the penal establishment on Cockatoo Island and the Iunatic asylum at Parramatta. It increased only in Western Australia from 1850, where economic collapse induced the Colony to accept convict labour and the cash infusion from expenditure on convict establishment upkeep. The Transport Department was kept busy arranging the movement of stores and troops, with a considerable upsurge during the second Maori War from 1863. The Commissariat's other main function was the letting of contracts against demands placed on it from the Ordnance, Army and Navy staffs but after the final departure of the garrisons in 1870 the imperial Commissariat was withdrawn. Remaining requirements for convicts in asylums and maintenance of the Royal Navy Squadron based on the Australian Station were handled by the Paymaster of the Royal Navy Depot retained in Sydney; residual convict establishment hangovers in the later convict repositories of Tasmania and Western Australia were accommodated by passing them within the following few years to the Colonial Governments on repayment of costs 18.

The end of the imperial Commissariat was not the end of commissariats in the Colonies. The habit had become much too ingrained to be discarded: they continued in each of the colonial administrative structures as a government stores organisation, which absorbed the colonial supply and ordnance functions transferred from the imperial Commissariat in 1850. This created little real change or hardship as the Colonial Secretaries and Treasurers had been carrying the estimates and funding of colonial as opposed to military activities from 1826. Titles and responsibilities varied between colonies: NSW, Victoria and Tasmania retained the quasi-military titles headed by a Commissary General while colonies which had had a minor or late imperial presence tended towards the civilian titles of storekeeper and clerk. That the titles were little appreciated Assistant Commissary General Blanchard found when appearing before a royal commission on the defence forces of New South Wales in 1893: confronted with a statement that he was really merely a storekeeper, Blanchard, veteran of the Suakin expedition and a major then lieutenant colonel in the militia, forbore to argue, acknowledging that he was indeed a storekeeper. Regardless of their pretensions or otherwise, these organisations generally provided support to hospitals, refuges and asylums, police, and other government departments and agencies 19. Their relation to the slowly emerging Colonial Military Forces was, however, considerably diverse.

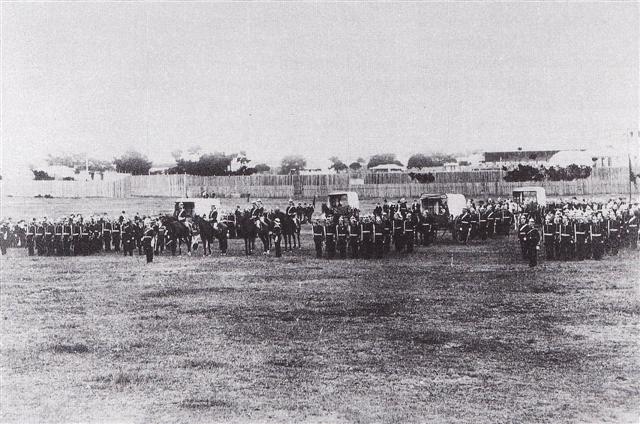

The earliest militias (artillery 1788, infantry 1794), loyal associations (Sydney and Parramatta 1800-08), cavalry/light horse (1803-25) and Royal South Australian Volunteer Militia (1840-51) were raised by governors and hence were clients of the imperial Commissariat. But the raising of forces by the Colonies from 1854 meant that the Colonial Governments were responsible for their maintenance. Until the formation of military supply and transport corps, the colonial volunteer, militia and permanent forces were supplied and had their members, horses, baggage and stores moved by civil and commercial resources. This local purchase and hiring was provided through a variety of mechanisms in different colonies at different times.

In Victoria supply of the Defence Forces was initially the function of the Commissary General of Government Stores, but this was transferred in 1885 to the Department of Defence with its own minister and secretary, which let contracts against demands from the Defence Force, authorised units to order on them and paid the bills; it also hired transport and controlled rail transport through its Ordnance Branch under Commissary General W.M. Cairncross, Controller of Naval and Military Stores. From 1886 a separate Commissariat Staff was established on the Commandant's Head-Quarters, setting the scene for the introduction of a military corps to act as its agent in the field to receive and distribute food, forage and fuel, but the rail transport function remained with the departmental Ordnance Branch 20.

The New South Wales Stores Office provided annual contracts for supplies and their delivery for all government departments to operate on, and specific ones for the permanent forces against which their families could also purchase. It was not active in the provisions and transport field for the volunteer and militia forces and the system evolved from military to Treasury control: before 1885 units purchased supplies and hired transport, within budgetary constraints, simply sending the bills to the Treasury Paymaster; in 1885, as an experimental move, the Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General of the NSW Force Head-Quarters called for tenders and let contracts for transport; in 1886 a board of officers appointed by the Commandant considered tenders and awarded contracts for transport, groceries, forage and firewood; then for the next two years Treasury took over, receiving demands from the Force, calling tenders and awarding contracts, a perhaps more comfortable arrangement in view of the very obvious political lobbying being exerted by potential suppliers. It was however less than satisfactory for a Defence Force committed to training for field operations, so a compromise was reached in which a Deputy Assistant Commissary General was given the task, with split responsibility to the Colonial Secretary through the Commissary General for contractual matters, and to the Commandant for the support of camp and field activities. This was partially satisfactory, particularly as the DACG in question was Blanchard who had the credibility of having been Commissary with the NSW Soudan Contingent and was now recommissioned to give the feel of being part of the military, but there was still lacking a military unit which could take the field as part of tactical operations 21.

Queensland's Colonial Stores, under the Colonial Secretary until 1885, thereafter the Colonial Treasurer, let contracts for government requirements ordered on by officers in charge and delivered by contractor to the required site, with a reservation of the right to procure supplies for the Defence Force at any time from other sources if required. Movement was procured by unit commanders using rail warrants. For camps, the Head-Quarters staff arranged movement by sea, rail, river transport and dray in carefully prepared movement tables, with unit officers seconded as transport officers at terminals; A Battery of the permanent Artillery was called on to provide transport for camps to reduce costs. In the Volunteer era, catering contractors supplied meals at 3/- per man per day but, after the introduction of militia in 1884, rations and forage were issued through a headquarters supply store, with a staff officer designated as Supply and Transport Officer. Commandant Maj-Gen G.A. Owen acknowledged the serious deficiency in the lack of a supply and transport service in 1894, but recommendations to this end foundered on budgetary limitations and the fact that defence plans revolved around close defence of port areas where such ad hoc measures could be tolerated. This persisted through to incorporation in the Commonwealth Military Forces 22.

South Australia also rested on expedient solutions to cover the lack of a formed supply and transport service with a Staff Adjutant and Quartermaster and a Military Storekeeper. The permanent Artillery had special contracts for food, fuel and forage operated on by the unit commander, while for the militia and volunteers, funds were budgeted for 'commissariat, transport, freight, hire of horses, fuel and rail transport' which were ordered by the military staff 23. Similarly Western Australia had contracts for supply and transport for the permanent artillery and engineers operating the coast defence forts, providing for volunteers by capitation grants and budgeting expenditure for annual camps, where volunteers 'cut up and issue rations' 24. Tasmania maintained a Store Branch in the Military Forces, using the standard expedients of contracts for the use of the Commander of Batteries, capitation for volunteers and auxiliaries, and budgeting for camp maintenance, freight and transport; the permanent artillery was used for supplementary supply and transport work. The Military Store was handed over to the Commandant's control in 1896, and a proposed transport section of an Army Service Corps was authorised but not implemented by Federation 25.

That Victoria should have been the first to raise a service corps prototype in Australia in 1886 might at first seem surprising when it is considered that New South Wales had, the year before, deployed a force to the Soudan, from which experience it might have gained a real understanding of the importance of the British Commissariat and Transport Corps' part in the success of the operation. Instead, the lesson learnt, on which succeeding military generations relied, was that providing combat troops to an allied big brother force is a very economical way of meeting defence obligations. There are, of course the debits: a far higher proportionate casualty rate; and the unlearned lesson that when such support is not available, there is neither the expertise nor the expansion capacity to match that of the combat elements.

Victoria's upstaging of its northern rival by the formation of its Ordnance, Commissariat and Transport Corps in 1886 was not due to any such appreciation. The motivation was sheer economy. And whilst economy has come to have very considerable military respectability as a principle of war and of administration, that was not the basis either. Rather, it was justified as a cheap way of feeding units during their annual training camps – the Corps provided 'value to the Commissariat Department'. Adoption of the Commissariat and Transport Corps title in 1889 and expansion to three sections in 1890 were not related to a field role. Nor did the adoption of the Victorian Army Service Corps title in 1895 mean that the experience of the British ASC was being adapted to the Victorian namesake. It remained an agent of the Commissariat Staff of the Defence Department until its absorption into the Commonwealth structure 26.

Neither was the NSW Commissariat and Transport Corps formed in 1891 for better reason: it drew caustic comment from a royal commission in 1893 as being a camp support rather than a field support organisation. This was taken up by Maj-Gen E.T.H. Hutton, appointed Commandant of the NSW Military Forces the previous year, whose operational experience of mobile forces in the British Army led him to pursue the means of supporting such forces in the field. As a beginning, the title was changed to NSW Army Service Corps in 1893, which not merely adopted the latest British title but provided a clear indication that the Corps was to render service to the Army, not the Commissariat. Provision was also made for the inclusion of a small permanent element and an expansion war establishment of six officers and 166 other ranks – modest achievements, but all that could be expected in depression budgets. This impetus, and that provided by his successor French, led to the raising of a second company in 1899 and a third in 1900 27. Within the new Commonwealth Military Forces the NSW ASC was able to provide the base for an early transformation into a field organisation to match the field force in that State; the Victorian ASC was a nucleus which could be expanded to support a smaller force in Victoria; but no other colony had yet raised a supply and transport unit 28.

For over a hundred years supply and transport support to the military forces in Australia had been provided by the imperial, then the colonial Commissariats. The absence of any serious need to provide for the support of expeditionary forces had placed no pressure for the development of military organisations capable of deployment with field armies. The Commissariats supported garrison forces and so continued with garrison procedures. They remained responsible either to far away masters in London or the Colonial Treasurers and Secretaries, so their actions were conditioned to that environment, a potentially crippling handicap to major operations which was eliminated in the United Kingdom after the Crimean War. These deficiencies in the Australian Colonies were largely masked by both the absence of warlike operations and the sheer practicality of the Commissaries, who strained where required to provide practical solutions to practical problems rather than hiding behind Treasury regulations, setting a precedent of meeting the task which their military successors would have to measure up to. So the Crimean imperatives were lost on dwindling imperial and embryonic colonial forces in Australia, the example of the emerging British military logistics system being eventually taken up as an economic expedient rather than as a battle tested necessity. It took the arrival of a battle tested veteran in the NSW Forces to focus attention on the real military need, which need then began to redirect activity, at least in the area which he controlled. For the remainder, the necessary impetus would not come until his reappearance in control of all the forces after Federation.

Footnotes

1. Herodotos lV.120, 125,128, 134; VII.20, 119, 184, 186-7; VIII.100,115; IX.39, 50-1; allowing for some gross numerical exaggerations on the Xerxes invasion, it is clear that the logistics system was meticulously planned and carefully implemented, just as were the Mardonius and Scythian denial actions.

2. Thucydides l.lxii.1; Vxlvii.6; VI.xxxi.3; VIII.xcv.4.

3. Polybius The Histories VI.39.12-15, 40.3-14.

4. Oman C. A History of the Art of War p189; Contamine P. War in the MiddIe Ages p26; Verbruggen J.F. The Art of Warfare in Western Europe During the Middle Ages p297- 8; van Crevald M. Supplying War p16, 18, 21, 17; Furze G.A. Provisioning Armies in the Field p29-30, 36-38; Thucydides I.xi.

5. Many military historians tend to rest solely on the facile answer of looting - see Crew G. Royal Army Service Corps p1 and Streidlinger O. 'The Union of Supply and Transport' Army Service Corps Quarterly April 1910 p538; however the reality lies more in such examples as Notes 1-4.

6. The following summary of the British Army background is based on: Fortescue J. The Royal Army Service Corps vol 1 ch III-IX; Crew ch 3-8; and Streidlinger 'Union of Supply and Transport'.

7. Historical Records of New South Wales vol I pt 1, James Matra's Proposal p7; Arden to Sydney 13 January 1785 Enclosure: Heads of a Plan p18.

8. Historical Records of Australia I.2 Hunter to Portland 10 June 1897 p19; NSW Archives NC 11/5 Copies of Government and General Orders 1810-1819 (4/1278) Order dated 3 September 1814.

9. HRA I.9 Macquarie to Bathurst 5 June 1817 Enclosure 3 Allen to Macquarie 10 May 1817, p435; Brisbane to Bathurst 28 April 1823, p26.

10. Brisbane T. Regulations as to the Issuing and. Accounting for Provisions and Other Articles furnished by the Commissariat to the Civil Departments of New South Wales and its Dependencies, p17; and many other fragmentary sources, prominently from HRA.

11. Harte H.G. The New Annual Army List 1845, p208.

12. Butlin S.J. Foundations of the Australian Monetary System p40-41, 48-49.

13. HRA I.6 Johnson to Castlereagh 11 April 1808, p213; Foveaux to Castlereagh 4 September 1808, p628; Bligh to Castlereagh 31 August 1808 Enclosure Palmer to Bligh 31 August 1808 and Sub-Enclosures 1, 2, p604-15; Bligh to Castlereagh 4 November 1808, p685-90; I.7 Bligh to Castlereagh 8 June 1809 and Enclosures, p107-14, 8 Jul 1809, p163.

14. HRA I.7 Macquarie to Bathurst 28 June 1813, p723; I.9 Macquarie to Bathurst 1 April 1817, p248-50; I.10 Brisbane to Bathurst 6 April 1822, p629-30; Australian Joint Copying Project War Office 58/116 Harrison to Lithgow 22 April 1823 f128. The 1811 restructuring gave Commissariat employees the status of: Commissary General – brigadier; Deputy Commissary General – major, and lieutenant colonel after three years; Assistant Commissary General – captain; Deputy Assistant Commissary General – lieutenant; Clerk – ensign; this was upgraded one notch by mid century.

15. HRA l.12 Darling to Bathurst 17 November 1826, p692; Darling to Hay 2 February 1826 Enclosure No 1, p152; NSW Blue Book 1828; NSW Archives Colonial Secretary Letters Received Ordnance Storekeeper to Colonial Secretary 14 April 1836; AJCP WO 58/118 Stewart to Laidley 18 March 1835, f133.

16. HRA I.8, p657 Note 19; I.12 Hay to Darling 9 March 1826, p214-5; I.13 Darling to Goderich 12 January 1828 and Enclosures 1, 2, p697-700; Huskisson to Darling 10 February 1828, p767-8; I.14 Darling to Huskisson 12 August 1828 and Enclosures, p332-3.

17. AJCP WO 58/118 Stewart to Laidley 18 March 1835 f133; WO 1/521, f731; Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1850 vol I Grey to FitzRoy of 21 November 1849; 1852 vol I, p758; Votes and Proceedings Queensland Legislative Assembly 1863 Session 2 Expenses of Military Service, p695.

18. AJCP WO 58/178 Stewart to Laidley 18 March 1835 f133; WO 58/121 Trevelyn to Ramsay 29 July 1847, f179; WO 58/122 Trevelyn to OC NSW 22 March 1853; NSW Archives Colonial Secretary 4/3657 Colonial Secretary to Commissariat 12 October 1869; Letters to Army Control Department 1870-78.

19. V&P NSW LA 1892-3 vol 7 Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Military Service of New South Wales, p129.

20. Parliamentary Papers Victoria 1887 vol 2 No7, No 25; 1888 No 25.

21. V&P NSW LA 1890 vol 2, p214-9, 224: 1892-3 vol 7 Royal Commission Report, p129.

22. Lindsay N.R. The Administrative Services of the Defence Force in Queensland 1824-1903.

23. Parliamentary Papers South Australia 1891 vol II Estimates 1891-92.

24. Western Australia Government Gazette 3 December 1895 Contracts; 29 April 1895 Regulations Under the Defence Act; 6 August 1897 General Orders Regulations Amendments.

25. Journal and Parliamentary Papers Tasmania 1896 No 20.

26. See Chapter 8 for a detailed description and references to the Victorian Corps.

27. See Chapter 7 for a detailed description and references on the NSW Corps.

28. Papers Presented to the Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia 1904 vol II Annual Report by Major General Sir Edward Hutton, p19; see also Chapter 11 first paragraph.

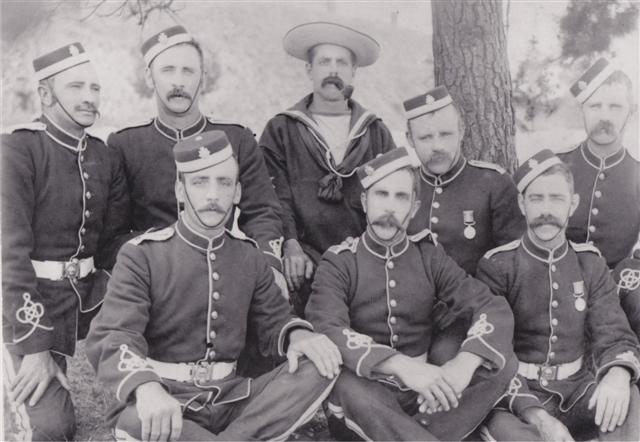

He began military service in the 85th Regiment of Foot in 1849 and in 1862 transferred to the Commissariat Corps becoming a staff sergeant in 1867. He served with in the Red River Expedition in Canada in 1870, retiring the following year and moving to South Africa.

He began military service in the 85th Regiment of Foot in 1849 and in 1862 transferred to the Commissariat Corps becoming a staff sergeant in 1867. He served with in the Red River Expedition in Canada in 1870, retiring the following year and moving to South Africa.